The Case for a National People’s Convention

Moral, Legal, and Practical Imperatives to Restore Our Republic

#unifyUSA Opinion

American democracy is falling apart, a slow-motion car wreck we’ve been watching for years. But this crash wasn’t caused by an outside force. We’ve been run off the road by our own founding document: the U.S. Constitution. We know—sacrilege! Yet it must be said. And as legal scholar Rosa Brooks puts it, it’s our collective worship of the document that’s tying us down:

How did it happen that the United States, which was born in a moment of bloody revolution out of a conviction that every generation had the right to change its form of government, developed a culture that so many years later is weirdly hidebound when it comes to its form of government, reveres this piece of paper as if it had been handed by God out of a burning bush, and treats the Constitution as more or less sacred? Is it really such a good thing to have a document written almost 250 years ago still be viewed as binding us in some way? How would we feel if our neurosurgeon used the world’s oldest neurosurgery guide, or if NASA used the world’s oldest astronomical chart to plan space-shuttle flights?

She’s right. The Constitution’s like a Macintosh computer from 1984. Innovative when it first came out; painfully inadequate for the tasks of today. We've tried to keep it running with patches and workarounds, but there's only so much you can do with outdated hardware.

Many people know this, yet they despair of making updates. Along with being the oldest on earth, the Constitution’s also the most difficult to change. Article V presents an absurdly high bar to clear. Since 1790, we’ve revised it only 17 times.

Americans feel caught in a trap: the Constitution's broken, yet it’s impossible to change. But what if it’s not? What if there was a way to revise or even rewrite it by going outside of its own amendment procedures? Could we imagine such a process, let alone achieve it? Yes, we absolutely can.

To understand why, we have to relearn the story of how the Constitution got here in the first place. The gap we feel between the democracy we want and the system we have doesn’t come from mere bugs in its design. It comes from intentional features—from a framework built for a different era, with very different priorities.

Reversing the Revolution

The popular memory of the American Revolution paints its outcome as inevitable. Its real history was anything but.

From 1761 to 1775, colonists asserted their rights as English subjects through protests and civil disobedience. But a funny thing happened on the way to history. In January 1776, an unknown immigrant named Thomas Paine published "Common Sense," turning strident dissension into radical revolution. The conflict transformed overnight, with Americans throwing off King George six months later and declaring themselves forever free.

A surge of egalitarian energy coursed through the land—the Spirit of '76. New state constitutions created the most democratic governments in Anglo-American history. For a decade, these revolutionary legislatures passed laws to provide the people economic relief and create a more equal society. Everyday citizens welcomed this. Wealthy elites, not so much.

Enter James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Concerned about the failing Articles of Confederation, and the disruptive wave of economic populism, they convened a constitutional convention in 1787. There they came up with some good ideas, ways to fix the basic functions of the central government. But they also enacted a more furtive agenda: ending the radical Revolution.

The real problem in America, they believed, was an “excess” of democracy. Their ideal was a “natural” aristocracy—rule by men of education, property, and status. Men like themselves, in other words. The delegates in Philadelphia repeatedly denounced government by everyday people. “Democracy is the worst of all political evils,” said Elbridge Gerry. Democracy “leads to amazing turbulence and violence,” Hamilton agreed.

The Constitution they crafted was rife with oligarchic features: huge congressional districts, indirect elections, long terms of office, and more. Each element was adopted to filter out the popular will and clip democracy’s wings. Most contemporary historians agree—the Constitution of 1789 was a bloodless coup of fifty-five aristocrats, an elite counter-revolution.

Why did the people ratify it? They weren't given much choice. It was either approve this new system or be stuck with the failing status quo. A recession was grinding on, and civil war—even foreign invasion—were real, looming possibilities. They had to take the good (a stronger national government) with the bad (oligarchy).

And in the end, they weren’t the ones making the decision, either. Instead of voting directly in a referendum, the people had to elect delegates to special conventions. It was these representatives—more elites—who got the final say.

The story didn't end there. The forces of democracy made a comeback with Thomas Jefferson in 1800. A champion for self-government who had missed the convention, his election as President was greeted as a second revolution. The democratic tide rose again, ending privileges like property requirements to vote and giving birth to mass political parties.

But the damage had been done. Americans found themselves with an evolutionary mismatch: The people had wanted democracy, yet their framing architecture designed aristocracy. The democratic soul was trapped inside an oligarchic machine.

The history of the United States boils down to this original, ongoing conflict. The democracy forces have risen twice: during the Civil War and Reconstruction, and again under the New Deal and Great Society. But each time, those advances have been undermined by oligarchic backsliding, enabled by the Constitution.

Beyond Article V

We now know the truth: the Constitution is opposed to self-government on purpose. In this, it stands as an obstacle to the democratic republic so many Americans have fought and died for. To win rule by the people, we must remake our founding charter.

But how? As noted, Article V's amendment process is ridiculous. Are we really stuck with this impossible mountain to climb? The answer is no. We the People can change our system of government any way and any time we want—even if it entails going beyond the Constitution itself.

History provides a precedent: the Convention of 1787! The delegates in Philadelphia were told by Congress to propose only amendments to the Articles of Confederation, not a fresh frame of government. But as soon as they locked the doors of the hall, they set to work writing a whole new system. And they had it ratified in ways that were openly unconstitutional. From the convening of its convention to its debates to its adoption, the birth of the Constitution went beyond the law at almost every step.

If the Founders could do it, so can we. As political agents, the people have the power to change our constitution however and whenever we like. All that's required is a shared plan, a critical mass of supporters, and the motivation to overcome the barriers. America’s like a neighbor trapped in a burning house—we must mount a rescue operation

Truth be told, we do this all the time. When we vote, petition, or organize a campaign, we engage in joint political action. And sometimes we take this shared power even further—through civil disobedience or when, as a jury, we nullify unjust laws. Holding a constitutional convention outside of Article V would just be an extension of this self-same sovereignty.

The Declaration of Independence proclaims this right unambiguously:

“Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government.”

Nothing can abrogate that sacred power—not even the Constitution. James Wilson, delegate at Philadelphia, proclaimed this truth five years after the convention: “The people may change the constitution whenever and however they please. This is a right of which no positive institutions can ever deprive them.”

Jefferson agreed. The dead hand of the past, he knew, cannot control the living. He thought governments should be revised every twenty years, and most nations have done so at about this rate. Americans are way behind. Time to catch up. Time to give our Constitution, and our country, new life. But how?

A Plan for a National People's Convention

In 2024, we've been practicing democracy far longer than the framers of 1787. We have the will, the scholarship, and the technology to outdo their primitive convention, both in wisdom and legitimacy. We can include vastly more than fifty-five people in the founding of our third American republic. Imagine a peaceful, deliberative process that harnesses the intelligence of the whole American public—a new democratic covenant, co-authored by 25,000 and ratified by all of us together.

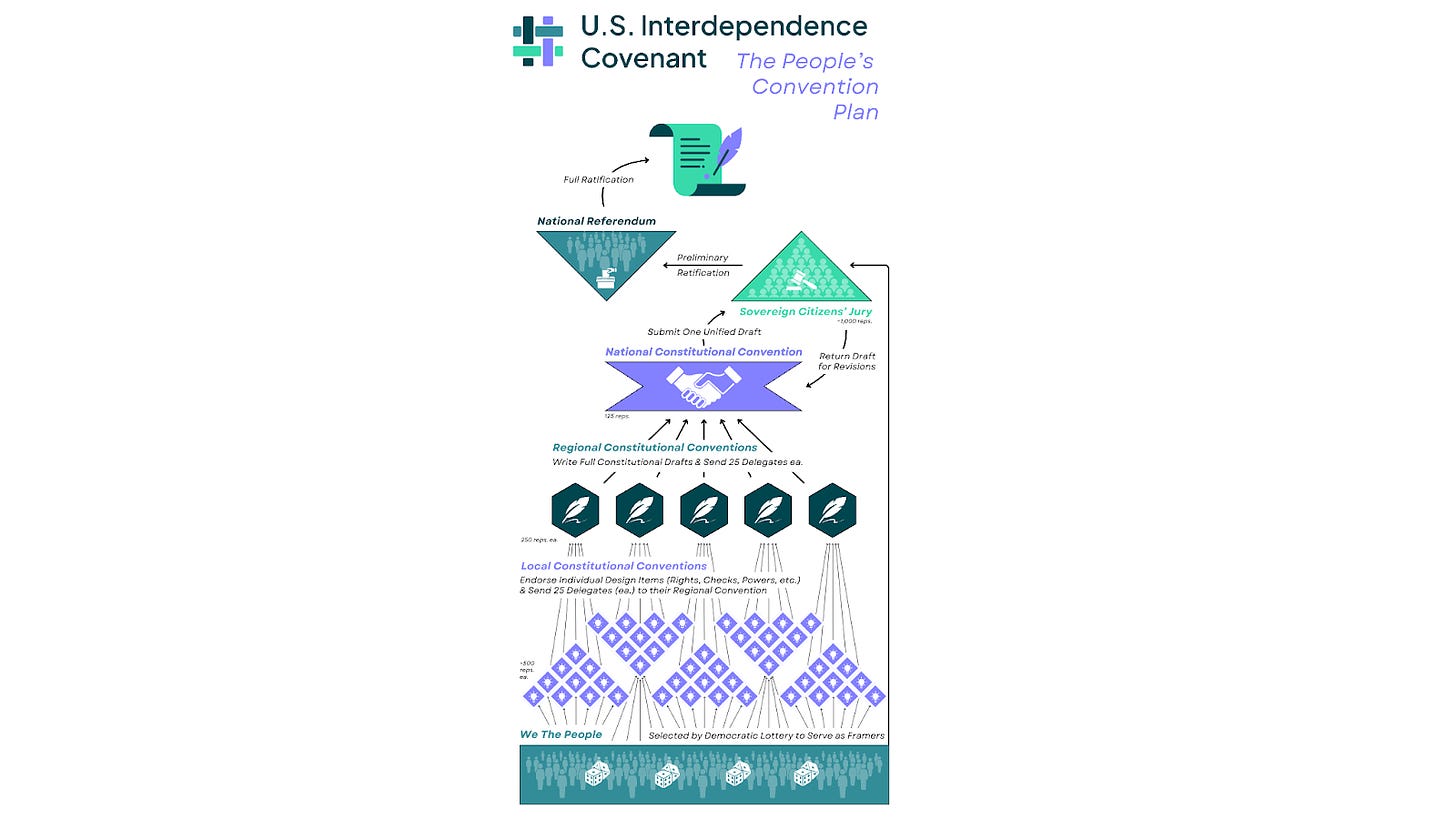

Impractical, you say? Too many cooks? On the contrary. This plan is founded on time-tested principles of sortition and deliberative democracy. It's a blueprint for turning "We the People" from a lofty ideal into living, breathing reality. Here's how it could work:

District Conventions: Establishing Popular Priorities

We start by drawing 50 temporary districts of equal population, grouping counties with a simple, neutral clustering algorithm. In each district, 500 randomly selected citizens participate in a convention. They're paid for their time and assembled in person, breaking into small groups of five to generate individual proposals and articulate their civic priorities.

A randomized committee distills these suggestions into about 100 mandates for the convention to vote on. The assembly then ratifies these mandates, recording their degree of support, to advance them to the regional convention.

To select delegates for the next stage, participants pick one delegate from each proposal group by secret ranked-choice ballot, based on who was the brightest and best to work with. These choices are then narrowed down to 25 by lottery, combining peer selection with random chance.

Regional Conventions: Democratic Drafting

Next, we combine districts into five regions and assemble conventions of the citizen-delegates chosen by their peers. A randomized committee distills and sorts the mandates into four categories, one for each branch of government, plus civil society. For each category, two groups of 25 turn their mandates into a draft constitutional article.

These draft articles are brought to the floor for open debate, deliberation, and synthesis. Self-organized caucuses can write full constitutional plans based on the deliberations. The goal is to pass a draft constitution with two-thirds support.

To send delegates to the National Convention, we repeat the internal ballot process, this time instructing delegates to consider diplomatic ability. Each region sends 25 representatives to the next stage.

A National People’s Convention: Consensus on Constitutional Transformation

At the national level, we form one neutral group of five (one from each region) to organize the proceedings. The rest of the delegates from each region present their plan, followed by an initial ranked-choice vote to select one plan as the working draft.

In small reading groups, delegates scrutinize and deliberate on the draft, eventually submitting formal objections to incomplete or dysfunctional clauses. New random working groups address each of these objections, likely borrowing ideas from the other four drafts. The assembly votes on each of these new amendments, approving them with a simple majority.

When all objections have been satisfied, the convention holds a vote on the entire draft constitution, which must pass by a two-thirds majority.

Ratification: The People’s Final Say

For the final stage, we select 1,000 citizens from the general American public to serve on a jury. This jury hears arguments for and against the new constitution, questions the authors, and then takes a vote. A two-thirds majority can send the constitution to a referendum to be ratified. If it fails to reach this threshold, the draft is returned to the National Convention for revisions.

The proposed constitution is published in full roughly a month before the special referendum. All citizens can vote for or against the new constitution, with no other measures or candidates on the ballot. A simple majority adopts the new constitution.

Conclusion

This process combines the best of direct and representative democracy. It harnesses our collective intelligence while ensuring thorough deliberation. By involving tens of thousands in drafting and millions in ratifying, we create a truly democratic foundation for our republic.

The Founders dared to reimagine democracy for their time. Now it's our turn to dream big, to craft a system that reflects our diversity, our values, and our aspirations. This People's Convention isn't just a possibility—it's our vocation.

Let's answer that call. Let's build a better framework to govern the United States for a future where we can all flourish in harmony with each other, with all of humanity, and with Earth.

#unifyUSA published a discussion paper with detailed information: A People’s Convention: Renewing the Constitution for the 21st Century

References

Ackerman, Bruce. We the People, Volume 1: Foundations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Amar, Akhil Reed. America's Constitution: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2005.

Amar, Akhil Reed. "Of Sovereignty and Federalism." Yale Law Journal 96, no. 7 (1987): 1425-1520.

Amar, Akhil Reed. "Philadelphia Revisited: Amending the Constitution Outside Article V." University of Chicago Law Review 55, no. 4 (1988): 1043-1104.

Amar, Akhil Reed. "Popular Sovereignty and Constitutional Amendment." In Responding to Imperfection: The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Amendment, edited by Sanford Levinson, 89-115. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Beeman, Richard. The Penguin Guide to the United States Constitution: A Fully Annotated Declaration of Independence, U.S. Constitution and Amendments, and Selections from The Federalist Papers. New York: Penguin Books, 2010.

Bouricius, Terrill. "Democracy Through Multi-Body Sortition: Athenian Lessons for the Modern Day." The Journal of Deliberative Democracy 9, no. 1 (2013): Article 11.

Bouricius, Terrill, and David Schecter. "Citizen-Led Constitutional Change." Research and Development Note, newDemocracy Foundation, December 6, 2018. http://www.newdemocracy.com.au/.

Dahl, Robert A. How Democratic is the American Constitution? New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Edwards, Donna, Mary Anne Franks, David Law, Lawrence Lessig, and Louis Michael Seidman. "Constitution in Crisis: Has America's Founding Document Become the Nation's Undoing?" Harper's, October 2019.

Foner, Eric. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Holton, Woody. Liberty Is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Klarman, Michael J. The Framers' Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Levinson, Sanford. Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (And How We the People Can Correct It) New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Nelson, Craig. Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. New York: Viking, 2006.

Ovetz, Robert. We the Elites: Why the US Constitution Serves the Few. London: Pluto Press, 2022.

Pettit, Philip. The State. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023.

Radwell, Seth David. American Schism: How the Two Enlightenments Hold the Secret to Healing Our Nation. Austin: Greenleaf Book Group Press, 2021.

Rana, Aziz. The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document that Fails Them. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.