Is it just me or does the United States feel on the edge of truly cracking up? The cascade of social shocks is coming so quick you can hardly keep pace. In recent weeks, two of the most explosive issues have detonated at once: abortion and guns. On May 2, Politico went public with a leaked draft of a Supreme Court opinion that would strike down Roe v. Wade. If that wasn’t enough, we’ve suffered two more back-to-back mass killings by attackers wielding legally-purchased firearms: one (an act of white supremacist terrorism) at a grocery store in Buffalo and the other—in a copy-cat crime of the Sandy Hook massacre—at an elementary school in Uvalde, TX.

These events have sent tremors through an already-fragile body politic. They’ve spawned endless rounds of hot takes, protests, recriminations, and fights. I was originally going to add my two cents and insist why the United States should enact strict gun laws and keep abortion legal. There are many sound arguments for these positions. But my sense is that, as with every political topic, it wouldn’t change many minds. If you already agree with me, you’d just nod along. If you don’t, nothing I say could possibly convince you otherwise.

So, I’m not going to do that. Instead, I want to draw your attention to the way that, once again, our decrepit constitutional system has failed us when it comes to these highly-charged subjects. Few items stoke the cultural divide like guns and abortion, a cold war that’s becoming increasingly hot. It seems like we’ll never resolve these fraught issues. But is it really the case that Americans can’t come to agreement? Or is it rather that our political process is inherently opposed to compromise and feeds on factionalism?

I. Guns

Let’s start with guns. When it comes to the question of why so many young men in America are going on rampages, the subject goes beyond firearms. Psychologists have been telling us for a while that we should understand mass shootings as suicides that “involve” homicides. They're really deaths of despair, the result of the same broken social bonds that have fueled the opioid epidemic, mental health crisis, and political polarization. Michael Pitarro, PhD, at Psychology Today, explains how a poverty of attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief lays the psychological groundwork for these shooters. If we can repair the fabric of society and instill resilience in young people, we’ll reduce pathological violence. This is yet another argument for religious democratic socialism.

Likewise, Dr. Stuart Brown led the first comprehensive study of mass shooters starting with Charles Whitman in the 1960s. Their finding? That a lack of play—yes, play—throughout the killers’ lives was the single most salient factor in their psychological profile. Is it merely a coincidence, then, that the rise of school shootings and other behavioral outbursts correlates with cuts to recess, P.E., the arts, and other forms of play in schools—and an increase in homework and high-stakes tests? In a society with the most work, greatest inequality, and least leisure of almost any on Earth, is it a wonder so many people—especially testosterone-driven males—are exploding?

But even with these broader ideas in mind, it’s a fact that when these young people go on a killing spree, they use guns. The social collapse just mentioned afflicts many countries and millions of souls. Yet we’re the only nation that suffers from such pervasive gun violence. So the question remains: what should we do about firearms? A Pew Research Center survey from last year found that a narrow majority of Americans, 53%, favor stricter gun laws. 32% think the laws are fine as they are, and 14% want to loosen restrictions. Seems intractable, right?

Yet behind this divide, the numbers are more promising. The survey went on to ask about specific areas within the overall topic. The answers are revelatory:

87% of Americans favor preventing people with mental illnesses from purchasing guns.

81% favor making private gun sales and sales at guns shows subject to background checks.

66% favor creating a federal government database to track all gun sales.

64% favor banning high-capacity ammunition magazines that hold more than ten rounds.

63% favor banning assault-style weapons.

56% oppose allowing people to carry concealed guns in more places.

57% oppose allowing teachers and school officials to carry guns in K-12 schools.

64% oppose shortening waiting periods to purchase guns.

79% oppose allowing people to carry concealed guns without a permit.

The survey reveals deep divides on guns between urban residents and rural ones; Blacks/Latinos/Asians and whites; Democrats and Republicans; gun owners and non-gun owners. But the fact remains that, despite these fundamental differences, there are many places where Americans have broad agreement. Huge majorities—two-thirds of the populace—think we should ban high-capacity ammunition magazines and assault weapons.

Instituting these policies alone would reduce the number and severity of gun massacres. The Los Angeles Times has an interactive graphic that shows how hundreds of lives could have been saved if these laws and others like them were on the books. The New York Times produced a similar visual last month in which they conclude that at least thirty-five gun massacres since Columbine—one-third of the total number—would have been prevented or lessened by these kinds of laws. Those thirty-five attacks slaughtered 446 people.

And yet, despite the fact that the vast majority of Americans favor these regulations, Congress has notoriously refused to pass them. Its obstinacy and corruption on this issue has become a morbid, macabre black comedy. Finally, nine days ago, a bipartisan group of Senators announced a deal on gun safety measures. But all it contains is a provision for enhanced background checks on select buyers and funding for states to enact—only if they wish—“red-flag” laws to confiscate guns temporarily from dangerous people.

Universal background checks? An assault weapons ban? A prohibition on high-capacity magazines? A Federal red-flag law? No. And the bill still has to overcome the filibuster. As a sign of the intense pressure that Republicans face from the gun lobby, no GOP Senator up for re-election in November endorsed the bill. Meanwhile, the Republican Party has cut hundreds of political ads since January that feature guns as talking points or visual motifs.

II. Abortion

Now, let’s turn to abortion. According to Pew, 61% of U.S. adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. 37% think it should be illegal in all or most cases. There are modest differences between whites and Blacks/Latinos/Asians; men and women; various generations; and white evangelicals and, well, all the rest of us. When you ignore white evangelicals, substantial majorities of Americans favor legal abortion across every demographic group.

But, again, behind these numbers, the story is more complex:

19% of Americans say abortion should be legal in all cases, no exceptions.

36% say it should be legal in “most” cases.

8% say abortion should be illegal in all cases, no exceptions.

27% say it should be illegal in “most” cases.

73% say abortion should be legal in pregnancies that threaten the life or health of the mother.

69% say it should be legal if the pregnancy is the result of rape.

53% say it should be legal if the baby is likely to have severe disabilities or health problems.

72% of Americans say that the statement “the decision about whether to have an abortion should belong solely to the pregnant woman” describes their views at least somewhat well. At the same time, 56% say the same about the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights.”

In other words, the survey shows that large majorities of Americans favor abortion access with certain restrictions. Few desire unrestricted abortion access and even fewer a total ban on abortion. When the survey probed further, it found something that most of us intuitively agree with: the stage in pregnancy matters. A sizable majority, 56%, think abortion should become illegal, at least in some cases, at some point during the course of a pregnancy. Turned around, when combined with the 19% who say abortion should be legal in all cases, 71% of Americans think abortion should be entirely legal at every stage or should be legal, at least in some cases, at some point in a pregnancy.

Where that point is, of course, is another question. In general, opposition to abortion grows as pregnancy progresses:

At 6 weeks into pregnancy, 51% of U.S. adults say abortion should be legal; 26% say it should be illegal; and another 19% say whether it should be legal or not “depends.”

At 14 weeks, 41% say abortion should be legal; 33% say illegal; and 22% say “it depends.”

At 24 weeks, (the point of fetal viability), 29% say abortion should be legal; 48% say it should be illegal; at 18% say “it depends.” (Of the 48% in opposition, 44% of them say abortion should be legal at 24 weeks in cases where the woman’s life is threatened or the baby will be born with severe disabilities. An additional 48% of them answer the follow-up question by saying “it depends.”)

To recap, a majority of Americans think abortion should be legal at six weeks into a pregnancy. A plurality think it should be legal at fourteen weeks. And almost half favor making it illegal at twenty-four weeks, with exceptions for the health of the mother or severe child disabilities. About one-fifth, 20%, say that all these questions “depend.” Just what they depend on isn’t defined. But this ambivalence speaks to the reality that, when it comes to this mysterious issue, much rides on the specific circumstances of each pregnancy. Unlike partisan activists, most people see a lot of grey when it comes to abortion.

Does our political system reflect these views? Let’s look. In 1973, the Supreme Court decided in Roe v. Wade to legalize abortion by a 7-2 majority. It found a constitutional right to an abortion, yet, like all rights, it’s not absolute. It must be balanced against the government’s interests in protecting women's health and prenatal life. The Court laid out a trimester timetable:

During the first trimester, governments could not regulate abortion at all, except to require that abortions be performed by a licensed physician.

During the second trimester, governments could regulate abortion, but only for the purpose of protecting maternal health—not for protecting fetal life.

After viability, abortions could be regulated and even prohibited, but only if the laws provided exceptions for abortions necessary to save the "life" or "health" of the mother.

As you see, this timetable coheres in broad strokes with the views of Americans today (whether they were the views of the public at the time is another question). The trickiest area is that second trimester. The Court protected abortion access at twelve weeks, but only 41% of Americans think abortion should be legal at fourteen weeks, with that agonized 22% saying “it depends.” That’s where the debate becomes most tortured.

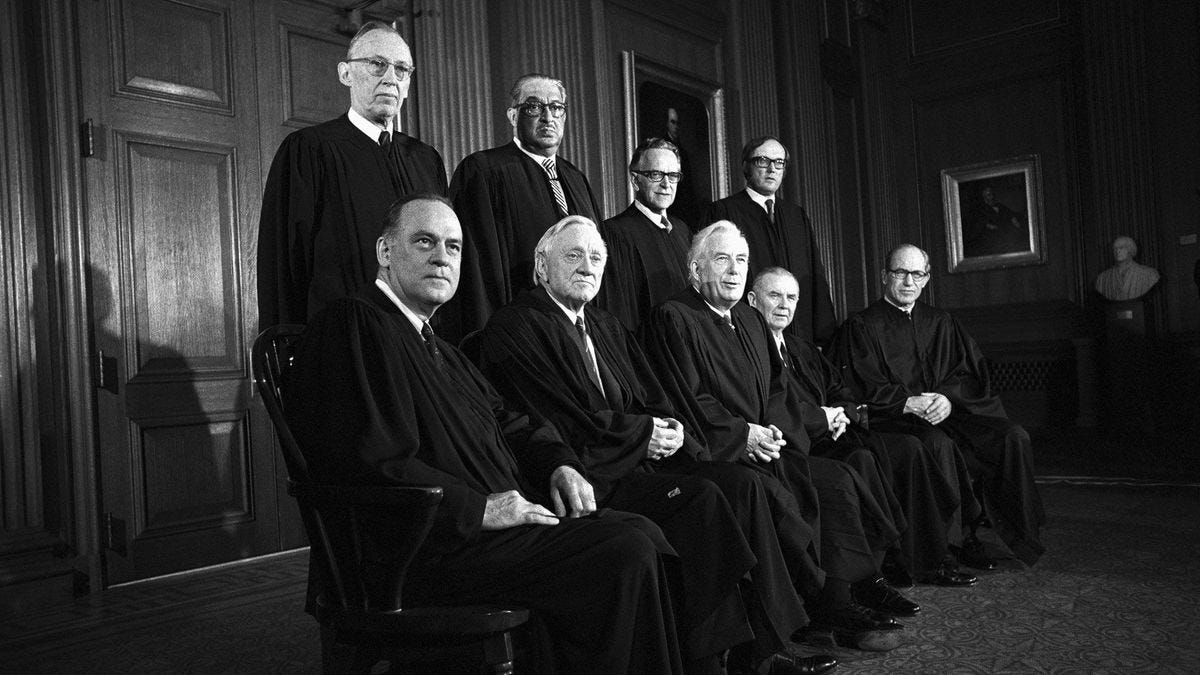

Of course, the problem with America’s abortion law is that it was handed down by a high court—not agreed upon by the people’s representatives in Congress. Some commentators, even liberals, argue that the Court should never have intervened in the democratic process to legislate from the bench. It polarized the public and gave the anti-abortion faction the mindset of righteous crusaders fighting a judicial diktat. It’s easy to gin up opposition when a law about a profound moral topic is decreed by a cabal of politicians in robes. It’s much harder, though, when the vast majority of citizens decide. For the most part, I agree that the Court should have refrained from weighing in on the issue. Abortion is an ethical question better left for all of us to decide, not nine lawyers.

Of course, it’s precisely by this same logic that the Court should refuse to rule on the issue now, as conservative columnist Bret Stephens points out in The New York Times. Yet in a matter of days, we could see it strike down Roe, take away a declared constitutional right (unprecedented in American history), and allow over a dozen states to institute a total or near-total ban abortion—against the wishes of the vast majority.

Chief Justice John Roberts appeared at oral argument to favor a narrow decision that upholds the constitutional right to abortion but allows states to ban it at fifteen weeks into a pregnancy. But our partisan electoral system—not to mention the Supreme Court—is not geared toward compromise. So, unless over the past few weeks he’s been able to convince another conservative justice to join him (Gorsuch or Kavanaugh being the likely contenders) the hard-right could soon issue a sweeping decision that will only make matters worse. In 2019, Pew found that a full 70% of Americans don’t want Roe overturned—including half of Republicans. Regardless what the Court decides, in the end, we’re talking about a seismic issue being determined—once again—by a tiny, reactionary, and (thanks to Clarence & Ginni Thomas) corrupt tribunal. Is there no better way?

(Roberts’s position, by the way, would actually get us to a place of reasonable compromise, given the complicated views that the Pew survey reveals. And it would bring the United States more in line with other Western countries. As this chart shows, of the twenty-seven nations in Europe that have legal abortion, twenty-one of them restrict access at twelve weeks—including Norway and Finland. Portugal restricts it at ten weeks. Spain and Austria restrict it at fourteen. Sweden restricts it at eighteen; the Netherlands at twenty-two; and the United Kingdom at twenty-four. So, a ban of abortion at fifteen weeks [with exceptions for the life and health of the mother and severe fetal disabilities] would still place the U.S. on the liberal end of the spectrum.)

III. The Irish Citizens’ Assembly

Anti-abortion activists claim that all they want is to return the issue to the democratic process and let state legislatures decide the matter. Of course, these ideologues don’t argue in good faith—the Republican Party, from its voter suppression laws to its packing of the Supreme Court to its election of Donald Trump—is one of the most fascistic, anti-democratic forces in the Western world today. And these activists have made their ultimate goal quite clear: an outright ban on abortion in every state and at the national level. Some even call for a constitutional amendment that prohibits abortion.

But even if they were arguing in good faith, is turning the issues of abortion and guns over to professional politicians a recipe for self-government? No. As I’ve argued in this newsletter, the electoral representative system is not a democracy. It’s an oligarchic process that allows special interests, activists, and dark money to capture Congress and stop representatives from listening to the will of the people.

The electoral duopoloy has further entrenched politicians in a bitter winner-take-all, zero-sum war. In this battle, extreme voices dominate the conversation (such that there is any) and pull lawmakers farther and farther from the middle. In New York, Buffalo Congressman Chris Jacobs, a Republican, just withdrew from his re-election race after he faced a backlash for supporting an assault weapons ban. And with abortion, partisan control of state legislatures leads not to carefully constructed laws that reflect the complex views of Americans, but to monolithic, all-or-nothing decrees. Many of them will go into effect automatically with the fall of Roe—no debate, no discussion, no dissent. Does that sound like democracy to you?

How can we rescue ourselves from this death spiral? You know my answer: democracy by lottery. But here’s where I don’t just have theory on my side—I have a real-world example. From 2016-2017, the Republic of Ireland convened a Citizens’ Assembly to address the country’s constitutional ban on abortion. One hundred everyday Irish men and women from all walks of life were called together by lottery. Over the course of five weekends, the Assembly met to confront the contentious issue. They studied briefing materials, learned the legal background, and heard presentations from twenty-five experts—doctors, ethicists, researchers, and more.

They also took testimony from seventeen advocacy groups and organizations on both sides of the debate, including the bishops of the Catholic Church, the Irish Family Planning Association, and the Church of Ireland. You can watch the testimony of these experts and advocates on the Assembly’s official YouTube channel. The Assembly took electronic submissions from the public as well. Finally, they listened to the stories of six anonymous women who’d experienced abortion in Ireland.

After each session, the Assembly deliberated and offered feedback. In the end, they took a series of votes and issued a report with recommendations. You can read the report in full here. The results were astonishing: On the first ballot, 87% of the members voted that the constitutional amendment banning abortion should not be retained in full. On the second ballot, 56% voted that amendment should be amended or replaced. On the third ballot, 57% recommended that amendment be replaced with a constitutional provision explicitly authorizing the National Legislature to address termination of pregnancy, any rights of the unborn, and any rights of the pregnant woman.

When it came to making a recommendation on the law, the Assembly spoke with clarity. 64% of the members recommended that the termination of pregnancy without restriction should be lawful. Of that group:

48% recommended that the termination of pregnancy without restriction should be lawful up to 12 weeks gestation age only.

44% recommended that the termination of pregnancy without restriction should be lawful up to 22 weeks’ gestation age only.

8% recommended that the termination of pregnancy with no restriction to gestational age.

In addition, a majority of Assembly members recommended the following reasons for which termination of pregnancy should be lawful:

Real and substantial physical risk to the life of the woman (99%)

Real and substantial risk to the life of the woman by suicide (95%)

Serious risk to the physical health of the woman (93%)

Serious risk to the mental health of the woman (90%)

Serious risk to the health of the woman (91%)

Risk to the physical health of the woman (79%)

Risk to the mental health of the woman (78%)

Risk to the health of the woman (78%)

Pregnancy as result of rape (89%)

The unborn child has a fetal abnormality that is likely to result in death before or shortly after birth (89%)

The unborn child has a significant fetal abnormality that is not likely to result in death before or shortly after birth (80%)

Socio-economic reasons (72%)

Finally, the Assembly issued five ancillary recommendations:

Improvements should be made in sexual health and relationship education, including the areas of contraception and consent, in primary and post-primary schools, colleges, youth clubs and other organisations involved in education and interactions with young people.

Improved access to reproductive healthcare services should be available to all women – to include family planning services, contraception, perinatal hospice care and termination of pregnancy if required.

All women should have access to the same standard of obstetrical care, including early scanning and testing. Services should be available to all women throughout the country irrespective of geographic location or socio-economic circumstances.

Improvements should be made to counselling and support facilities for pregnant women both during pregnancy and, if necessary, following a termination of pregnancy, throughout the country.

Further consideration should be given as to who will fund and carry out termination of pregnancy in Ireland.

The Assembly released its report to the National Legislature on June 29, 2017. A special committee of the Legislature met to review the recommendations, and it published its findings on December 20, which you can read here. On May 25, 2018, a national referendum was held on whether to repeal the constitutional amendment and allow the Legislature to regulate abortion. In advance of the vote, the Legislature produced a proposed bill so the public would be informed of what would become the new law, should they vote yes. The referendum passed by a majority of 66.4%—almost exactly the same percentage as the Assembly. In its wake, the Health Act of 2018 was introduced into the National Legislature. It passed through both chambers and was signed by the President of Ireland on December 20, 2018. On the first of January, 2019, legal abortion services commenced in the Republic.

The final law allowed for abortion without restriction up to twelve weeks of pregnancy. It banned it after that, with exceptions for the life or health of the mother. As you can see, this was a more conservative position than the Assembly recommended. 52% of the Assembly favored allowing unrestricted abortion up to twenty-two weeks. The politicians, however, decided on a narrower law, perhaps to garner as much support as possible. 64% of the Assembly favored a twelve-week limit—a better recipe for long-term stability around the issue. Despite this deviation, the experience produced trust and cooperation among all parties.

IV. Conclusions

The results of the democratic experiment just summarized are extraordinary. Let’s start with the sheer fact that in Ireland—a deeply Catholic country for almost all its history—two-thirds of the populace decided to legalize abortion when they had a chance to study the issue and deliberate in freedom. This was even after hearing directly from the Catholic bishops, as well as other anti-abortion groups and doctors. Despite decades, nay centuries, of the Catholic Church denouncing abortion from every quarter, the people decided otherwise. You can look at this in two ways: either Irish Catholics were never listening to their leaders, or their leaders were never listening to them. Given that those leaders were uniformly unmarried, unaccountable, and male, my money’s on the latter.

Secondly, look what happens when you get politicians, judges, and special interest groups out of the room and allow everyday people to listen to experts and dialogue amongst themselves: An informed, civil, intelligent discussion is had and a workable compromise reached. The Assembly’s report is striking for its nuance, detail, and precise parsing of the issue—far from the bombastic, ideological, and inflexible pronouncements made by America’s politicians and courts.

Would we reach the same conclusions as the Irish if we adopted a similar process? Hard to say. Ireland isn’t as diverse as the U.S., and it lacks the presence of reactionary white evangelicals. Still, it’s fair to assume that if we had a citizens’ assembly on abortion, we’d reach an agreement that better reflected the views of everyday people. Same with guns. That’s the heart of self-government.

Citizens’ assemblies are no guarantee of salvation—in the end, partisans have to agree to lay down the sword and make peace. No country understands this better than Ireland. If citizens’ assemblies in America finally reached middle ground on guns, abortion, and other issues, would the extremist minorities who dominate the scene abide by the will of the majority? Or would they continue on the war path, convinced that these are existential issues that cannot be compromised? I hope for the former. I fear for the latter.

On this note, it’s worth pointing out that the obsession with rights in this country bears a lot of blame for our inflamed conflicts. The Irish Citizens’ Assembly didn’t focus on whether there is or isn’t a constitutional right to an abortion. It just decided that legalizing abortion made for the best social policy. When you turn something into a “right,” you make it sacrosanct and instill in people a fierce, unyielding individualism.

Here (as legal scholar Jamal Greene tells Ezra Klein below) the United States is again unique among nations—and not in a good way. Compared to other constitutions, ours recognizes few rights (thirty-five) but protects them strongly. Most constitutions enumerate more rights, but moderately so. They understand that rights often conflict with each other, and that governments must craft laws that balance competing interests and strive for the common good.

You can’t make a right absolute. If you do—if it becomes constitutive of your identity, morality, and very way of life—then compromising with others who express reasonable differences becomes not a noble, win-win solution, but a craven, corrupt capitulation. It’s cooperating with evil. And so, the first step back from the brink is to relinquish our Manichaean worldview. That’s hard. It’s more satisfying to believe you fight for the good—or even God—while your opponents are orcs. But we all must try, before things fall apart. Democracy by lottery can help.

When a constitutional order fails for decades to legislate according to the will of the people, it becomes morally bankrupt. At this point, ours is barely legitimate. Will our feckless, grey leaders wake up, see Ireland through their spectacles, and follow suit? Let’s pray. As Orwell said eighty years ago:

A generation of the unteachable is hanging upon us like a necklace of corpses.