I. Pilgrimage to The Savior

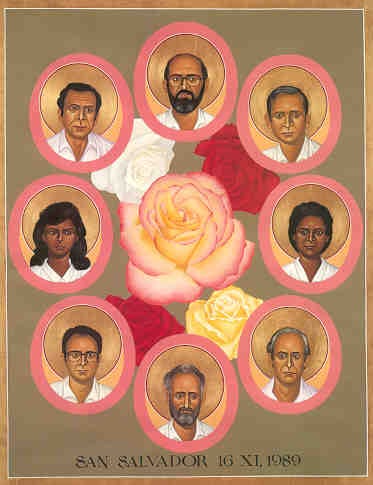

In the spring of 2012, I traveled to El Salvador with a contingent of students from Boston College, where I was pursuing divinity studies. We spent a week in the tiny Central American country, pilgrims tracing the history of its embattled, suffering people. In San Salvador, we visited various parishes and social service agencies doing amazing work, such as a home for orphaned teens. We toured the national legislature and met with leaders of the two major political parties, including that of the former rebels. We stood in the garden on the campus of the University of Central America, where six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter, were assassinated by a U.S.-backed death squad in 1989. And we paid our respects to Archbishop Oscar Romero at the chapel where he was gunned down in 1980 while presiding at Mass.

The highlight of the journey was the two days we spent in a village in the campo, where we were hosted by various families. We ate, slept, and played with the residents, poor in wealth but rich in spirit. And friend and I stayed with a family who’s house lacked a proper roof. Their little boy, Hector, delighted in showing us the premises, including a wild turtle who’d made a dwelling in a corner of the inner courtyard. We kept his grandfather up late that night, telling us stories about the old times. On the morning of the second day, our guide led us to a grove on the edge of the forest. There, an old man with a leathery face greeted us. For the next hour, we sat in rapt attention as he mesmerized us with an oral history of the village:

Once upon a time, our family—like all in the village—led hard lives. We labored heavily in the fields to survive, had no education, and lacked all hope. At times our hunger got so bad we’d pass out during Mass, a confusing, superstitious ritual conducted in an archaic language (Latin) that we didn't understand. All we knew is that we had to go to receive grace, obey the authorities, and avoid eternal damnation. The priest, his back to us at the high altar, would stop, turn around, and say, “Why did that man collapse?” “Father,” we’d reply, “we are so hungry. We are fainting because we have no food!” “Ah, yes,” he’d sigh, “Life is full of pain. But suffering brings us closer to God. Wait a little longer, and you will die and go to heaven, where you will eat rich fare.” With that, he’d resume his mysterious rites.

Then one day, about 1970, the village showed up to Mass to find a new priest, a young priest. We proceeded with the Eucharist like always. But this Sunday, it was different: he was speaking our own language. For the first time, we understood the words of the Gospel passage. We comprehended the prayers, too. Most shockingly, the priest faced us, arms open. As usual, someone fainted. The new priest stopped. “Why did that man collapse?” “Father,” we replied, “we are so hungry. He passed out because we have no food!” The priest looked at us intently. “And why don’t you have any food?” We stared at each other in bewilderment, then looked back at him. “Father, you know very well why. Life is full of pain. But suffering brings us closer to God. When we die, we will go to heaven, where we will eat rich fare.” His face darkened. “And who told you that?” “Why, our priest told us!” we replied. Then something extraordinary happened. The young priest got down from the sanctuary and sat in our midst. We encircled him, unsure what was going on. He gazed in silence, then spoke: “God does not wish you to suffer. God wishes you to be fed. Let me tell you about a man named Jesus.”

For the rest of the day, and over the weeks to come, the priest told us about the life and works of Jesus of Nazareth—a simple laborer like ourselves, who healed the people of his time and proclaimed Good News to the poor, a year of Jubilee for the oppressed. We had never heard such stories, or rather, never heard them offered in our own tongue, addressed to our own situation. In the ensuing months, we transformed our parish and community with the aid of the priest. We created Bible study groups where we read the text in Spanish and talked about its meaning. We held classes on the history of El Salvador and learned about the exploitative economic system that had reduced us to penury. Most of all, we developed a relationship with Jesus, inspired by his life and teachings. It was like a blindfold was untied from our eyes.

Hope and tragedy followed. The village began to organize itself to resist the abuse we suffered at the hands of wealthy landowners. In response, the military stepped in and began to crackdown. The first atrocities occurred, including the rape and murder of a girl. All over the country, peasants rose up and fought back. We had a powerful voice in Monsignor Romero. But when he was killed, it was the last straw. The Army occupied the town, and we fled into the jungle. For the next decade, we lived on the edge of civilization, joining the rebels and enduring the most appalling crimes and massacres. Many martyrs were made, many lives lost. But it didn’t matter. We’d awakened to a freedom and dignity no bullets could kill.

II. Conciliar Counter Attack

I tell that story because it’s the kind of marginal event—involving forgotten people—that Catholics in the United States continue to ignore when assessing the impact of the Second Vatican Council. This month marks sixty years since the opening of the seminal gathering of the Catholic Church. In a recent opinion piece in The New York Times, columnist

uses the Council’s anniversary to take stock of its legacy, adopting a parochial perspective typical of American commentators. If he thinks of a place like El Salvador at all, it’s to write it off as a sideshow.I’ve read Ross frequently over the years, including his 2008 book Grand New Party and The Decadent Society of 2019. I tend to find him a smart conservative and good writer. As a columnist for the Times and film critic for National Review, he occupies a privileged perch from which to shape public taste around politics, religion, and culture—I’m more than a little jealous! Though I often disagree with his judgments, he’s thought-provoking in a good way. At best, he attends to nuance and fairness, creating taxonomies that orient readers to the terms of debate.

Which is why his piece from October 12, “How Catholics Became Prisoners of Vatican II,” is so shocking. He’s distinguished himself in recent years for his brazen criticism of Pope Francis, whom he’s labeled a heretic (along with a number of others, like theologian Massimo Faggioli). According to him, the Holy Father’s “plot” around the question of allowing divorced Catholics to receive communion started an ecclesial “civil war” (Ross’s euphemism for “open debate”). This fictitious papal intrigue (not, you know, the actual intrigue of clerics like Carlo Maria Vigano, Raymond Burke, and many American bishops) will lead to schism if left unchecked. This is all spurious. But in this latest column, he outdoes himself in his blinkered approach. In a few hundred words, he pronounces sweeping judgment on the Council, one of the most immense, complex, and transformative events in religious history. Eschewing any attempt at intellectual inquiry, he declares it a failure. Necessary, perhaps, but a failure nonetheless:

The Second Vatican Council failed on the terms its own supporters set. It was supposed to make the church more dynamic, more attractive to modern people, more evangelistic, less closed off and stale and self-referential. It did none of these things. The church declined everywhere in the developed world after Vatican II, under conservative and liberal popes alike—but the decline was swiftest where the council’s influence was strongest.

As evidence for this breathtaking claim, he offers a grab-bag of complaints, each one built on straw. “The new liturgy,” he says, “was supposed to make the faithful more engaged with the Mass; instead, the faithful began sleeping in on Sunday and giving up Catholicism for Lent.” Rather than engaging the world in a positive vein, he argues, the church became consumed in left-right squabbles that simply fell along the partisan lines of the culture wars. The Council ushered in an era of “middling” guitar music and “ugly” modern architecture. Even more disastrously, its sea change in practice “made ordinary Catholics wonder why an authority that suddenly declared itself to have been misguided across so many different fronts could still be trusted to speak on behalf of Jesus Christ himself.” He concludes with an astounding sentence in which he compares the Council to the cross of Golgotha, its “unnecessary breakages” causing wounds that will remain even in some future resurrection.

Douthat insists that his piece “isn’t a truculent or reactionary analysis.” It’s never a good sign if you find yourself making such a preemptive rebuttal. Because that’s exactly what his essay is. When Dorothy Day called the church the cross on which Christ is crucified, I don’t think she had Vatican II in mind. But I also don’t know if Ross is a fan of her radical form of Catholicism. His dubious claims about the Council calls to mind the late John W. O’Malley’s critique of another piece by Douthat from 2014: “Mr. Douthat’s arguments are so loaded with questionable assumptions, historical and theological short-cuts, and parti pris that it is difficult to know where to begin.”

Other commentators have joined the chorus. Faggioli, who’s sparred with Ross in the past, pushes back strongly in La Croix. He notes how such cheap attacks by traditionalist Catholics in the Times ironically comfort the paper’s skeptical readership, as they confirm the negative image liberals hold of the church: a rat’s nest of backbiting, feuds, and hatchet jobs that target the most inspiring pontiff since John XXIII:

It’s like looking through a keyhole and seeing this weird world of Catholicism vie with itself, where devout believers try to take down the pope as if they were students in a graduate seminar trying to impress the professor. There are Catholic ways for Catholics to disagree with the pope in public. But this is obviously not something they teach in Ivy League universities.

On Twitter, David Gibson, Director of Fordham’s Center on Religion & Culture, posted a sharp thread that picked apart Douthat’s tendentious claims:

Meanwhile, over at his excellent blog, Where Peter Is, Mike Lewis offers a sound distillation of the problems with Douthat’s approach. “Like past councils,” he says, “Vatican II taught on matters of doctrine and morals, and to frame the promulgation of such teachings in terms of ‘success and failure’ or ‘support and opposition’ is bizarre.” He continues:

[Douthat] doesn’t delve into any significant debates over theology or the proper interpretation of the Council. Really, in this column he’s opining on little more than the on-the-ground changes Catholics in Western society experienced following the Council. And he uses the types of talking points regularly found in places like First Things or Crisis or The Catholic Thing. His commentary has very little to do with the Council—or even its implementation—itself. It’s more of a polished-up rehash of conservative Catholic gripes and grudges about Church architecture and hippy priests and guitar Masses and CCD teachers from a generation before he was born.

III. A Literary Convert

It bears keeping in mind that Douthat isn’t a trained theologian. He has no degree in religion at all, in fact, just a Bachelor’s in history and English from Harvard (for a full profile, read the university’s official magazine). He converted to Catholicism with his mother at age 17, after a peripatetic period in which she abandoned the Episcopal Church of her youth to follow a charismatic faith healer around New England (she suffered from debilitating allergies). Combined with his devouring of Anglo-Catholic writers like Chesterton, Tolkien, and Evelyn Waugh, crossing the Tiber provided the teenager with psychic peace. Those authors (whom I also love) are key to understanding his political and theological disposition.

Along with fellow traveler C.S. Lewis, they stood as apologists for a certain kind of English Christianity: bookish, tweedy, creative, itself a throwback to the Middle Ages (not, however, to the ancient church). It’s a Catholicism defined in opposition to an overwhelmingly Protestant and secular culture. Thus, they made for perfect models as Ross departed for Cambridge, MA—a brick-and-ivy neighborhood where the Inklings would’ve felt at home—to combat the hedonistic culture of bourgeois privilege. He’s hewed to this disputatious approach through stints at The Atlantic and First Things, and now at the Times.

Ross prides himself in his ability to know the liberal mind from the inside, identify its suppositions, and then turn them against its hypocrisy, excesses, and inconsistencies. At best, this is helpful and entertaining. At worst, though, he deploys asymmetric arguments that aim for third-way insight but instead blow hot air in an effort to own the libs. His columns and interviews have, at times, displayed a callous indifference to the plight of poor pregnant women; downplayed the threat of Trump; and poo-pooed the violence of the January 6 insurrection. In these moments, he comes off as a cheeky poseur attempting to confuse the other side through “hide-the-ball” tricks that play fast and loose with the rules. Which is, well, very Harvard.

A public intellectual is paid for his opinion on a range of matters for which he has limited, if any, formal expertise. Douthat’s clearly well-read and engaged on church matters for someone who’s never studied theology. And as Kaya Oakes argues, we all have the right to sound off on any topic we wish, especially about a religious tradition to which we belong. I’m not trained in history or politics, yet I write about them regularly in this newsletter. But—and here’s the point—when I do venture beyond the realm of my training, I try to exercise discipline. I stick to the masters as much as possible, and avoid totalizing interpretations or reductive arguments. And, certainly, I’d never feel comfortable passing judgment on the ideological purity of others in that field. Nor would I expect readers to give my ideas equal weight as experts. If I wrote about science and medicine and made dubious claims, it would be only right for professionals to debunk them and audiences to ignore me.

Hence this post. I was lucky to take a course on Vatican II in graduate school, where I studied the Council in depth. That doesn’t make me an expert, but when it comes to this topic, I probably have a deeper understanding than most interlocutors—certainly than Douthat. What’s baffling in the ongoing controversy about the Council is how little the partisans involved actually know about it. In his column, Ross makes sloppy mistakes and misreadings that betray a lack of basic understanding of the Council’s history, texts, and reception (or, what’s worse, a hostile bias against them). Take his statement that the goal of its conveners was “to make the church more dynamic, more attractive to modern people, more evangelistic, less closed off and stale and self-referential.”

That was one of the Council’s goals, yes, but hardly the only or even the most important. And even this one needs to be grounded in specific terms and historical analysis. What is modernity? What is dynamism? What is the evangel itself? He doesn’t do such spade work. And then he has the audacity to claim that the Council failed to achieve these outcomes. Really? I’d argue the total opposite: that it made great, if incomplete, strides at doing so. That the drop in numbers since then might, just might, have other causes, and that it happened in spite of the Council’s refreshing reforms—not because of them. Correlation doesn’t prove causation. Has Douthat never encountered the notion of extenuating factors or unintended consequences?

For example, could the American decline in church affiliation owe something to broader trends in rich, lonely, capitalistic societies—the very ones Ross pinions in The Decadent Society? Likewise, could the child sex abuse scandal maybe, just maybe, have more to do with the loss of institutional trust on the part of the faithful than changing the text of prayers, which was welcomed by most of them? Or, for that matter, the abandonment of the Council’s invitational rhetoric by American bishops in the 1990s and their adoption of the old confrontational approach, especially on matters of sexual morality? Douthat likes to engage in counter-factual history, but there’s no parallel universe I can imagine in which a Catholic Church without the Council boasts mega-membership in 2022 America. If anything, those rewrites feature a church on life support, if alive at all.

The truth is, in many ways the Council was a victim of its own success, not failure. Its changes were so welcomed that they’ve become part of the wallpaper, fading into the background as the generations that knew the pre-conciliar world or came of age during the Council and its immediate aftermath die out. Those Gen X and Millennial Catholics who approve of the changes don’t see their import anymore, nor feel the need to defend them (when I was explaining the Council’s declaration on religious liberty to a div. school friend, he shrugged his shoulders. “Isn’t that obvious?”). Heroes of the Council—like Yves Congar, Henri de Lubac, and Joseph Suenens—go unsung. If anything, liberal Catholics—especially Gen Z—want the church to make further updates in the direction that Vatican II took, to finish the job. So, they fail to study what happened from 1962-65 with much rigor. On the other hand, young conservatives, pining for a triumphal church they know of only from their dreams, have a lot to gain in seeing the Council discredited. Hence their distorted readings.

IV. Grand Tour

But to paraphrase our illustrious President, Vatican II is a big fucking deal. Consider the following:

The Council was quite possibly the largest meeting in the history of the world, i.e., a gathering with an agenda on which sustained participation of all parties was required and which resulted in actual decisions. It was such a massive undertaking to prepare that two and a half years passed between its announcement and its opening. 850 clerics from priests to cardinals worked over these years to prepare for it.

It was only the second council in 400 years since Trent, and almost a hundred years since Vatican I was suspended, unfinished. Moreover, it was the first ecumenical council convened in the presence of modern media. Over 10,000 journalist credentials were issued. The media played an important role in what happened.

It was the first global council, featuring bishops from 116 different countries. Europeans dominated the proceedings, but for the first time, indigenous bishops from other continents participated. 36% were from Europe; 34% from the Americas; 20% from Asia and Oceania; and 10% from Africa. Indeed, it took place during decolonization.

The first eight ancient councils took place in the Greek-speaking world. The remaining thirteen in the Latin. The decision at Vatican II, then, to admit non-Catholic observers (Protestants) as an integral body was unique in the annals of church history. It also allowed deliberations to be reviewed by scholars and churchmen who did not share many of the basic assumptions of Catholic doctrine and practice. There were 182 such observers or guests by the end. This led the bishops to avoid becoming inwardly focused.

There were 2,400 bishops participating at any given time in the basilica. 253 died during the four years and 296 new ones added. This amounted to a total of 2,860 who attended part or all of the four periods. In comparison, only 750 bishops had participated in Vatican I; Trent opened with just twenty-nine. Its largest sessions barely exceeded 200. 484 theological advisers were appointed to Vatican II by the two popes. 50-100 observers from other churches were also invited to attend. Added to this were various groups with business in the Council, meaning that during the four sessions, 7,500 people were present in Rome at any given time because of Vatican II.

It lacked a unifying theological framework. Previous councils used neo-scholasticism as their conceptual hermeneutic. Not so Vatican II.

It was unprecedented in the volume of product. Its documents alone constitute 30% of the production of all ecumenical councils put together. It alone generated 12,000 lines of text—the other councils, combined, produced 37,000 lines. Its closest competitor was Trent, with 17 volumes of documents. Vatican II produced thirty-two, many running more than 900 pages. It also generated hundreds of unofficial documents, such as diaries, correspondence, reports, and commentaries in newspapers and journals. Only a fraction of these have been published.

Impressive, you might think. But just what does all this have to do with my tale of El Salvador? Everything. The young priest who helped liberate the village had been formed by the teachings of the Council and its 1968 successor conference in Medellin, Colombia. The Latin theologians’ embrace of Christian base communities and preferential option for the poor inspired him to enter into solidarity with the peasants and expose them to Jesus—who he was, what he wanted. Without Vatican II, those people might very well have eked out their lives in ignorance and degradation, never knowing the taste of spiritual emancipation that the Gospel brings. For them, the pre-conciliar church buttressed the country’s tyrannical regime and left them exploited and passive. Only through the reforms of the Council did they come to know the love of Jesus and experience his healing, hopeful, liberating message. That, in my book, is the ultimate success.

In the next few editions of this newsletter, I’ll do my best to take you through the ecclesial backdrop to the Council and the intentions of its participants; the history of the Council’s debates and summaries of its texts; and its subsequent reception and impact, which are ongoing. This is a little awkward, given that I’m no longer a Catholic but a traitorous Episcopalian (a fact that Douthat might take as proof of his thesis). But just as an expat overseas has a certain purchase on the dynamics of his mother country, so too does my existential and conceptual knowledge of Catholicism aid me now in seeing Rome from the outside. Once a Catholic, always a Catholic, they tell me. And as with political refugees, so we recovering Catholics look back on our former home with an admixture of affection and pain.

Moreover, Vatican II was a gift to the whole Church of Christ, not just Rome. Though it took four centuries for the Vatican to make peace with the Reformation and accept Luther’s ideas, when it finally did so, the theology it provided grounded the entire People of God. It was a new appropriation of the Gospel, which the church undergoes every generation, and which itself will require decades to unpack. As a colleague once told me, it takes a hundred years for the Catholic Church to receive a Council. This is especially so of a gargantuan one like Vatican II.

In fact, it’s doubly true in this case because the Council was full of inconsistencies, compromises, and contradictory impulses. German theologian Hermann Pottmeyer has described it as an unfinished building site, with much work left to do. What we have, he says, are the ruins of a Baroque church with four new columns rising from the rubble: the teachings on the church as the People of God; the church as the sacrament of the Kingdom; the collegiality of bishops; and on ecumenism. We await a dome to connect the columns—i.e., an internally coherent ecclesiology that will integrate the Council’s teaching on episcopal collegiality with its theology of the local church.

Over the coming posts, I’ll take you on a close inspection and grand tour of this building site, including the all-important ancient foundation that lay beneath the Baroque edifice, which the Council sought to reveal. Untutored eyes fail to appreciate great beauty—close up, the Sagrada Familia looks like a dripping sandcastle. I hope to sharpen your vision, so that you’ll see the architecture of Vatican II not as some brutalist monstrosity, but as a sublime, if incomplete, rendering of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for a new age—one that cleaned off the grime of centuries of decay to let the colors shine forth once more. In this, I’ll try to emulate Richard Gaillardetz, my teacher on the Council and one of its major theological interpreters. Rick’s in the advanced stages of terminal cancer, making the final portion of his journey with the Lord. I’d like to dedicate these posts to him, in gratitude, and in prayer.