I.

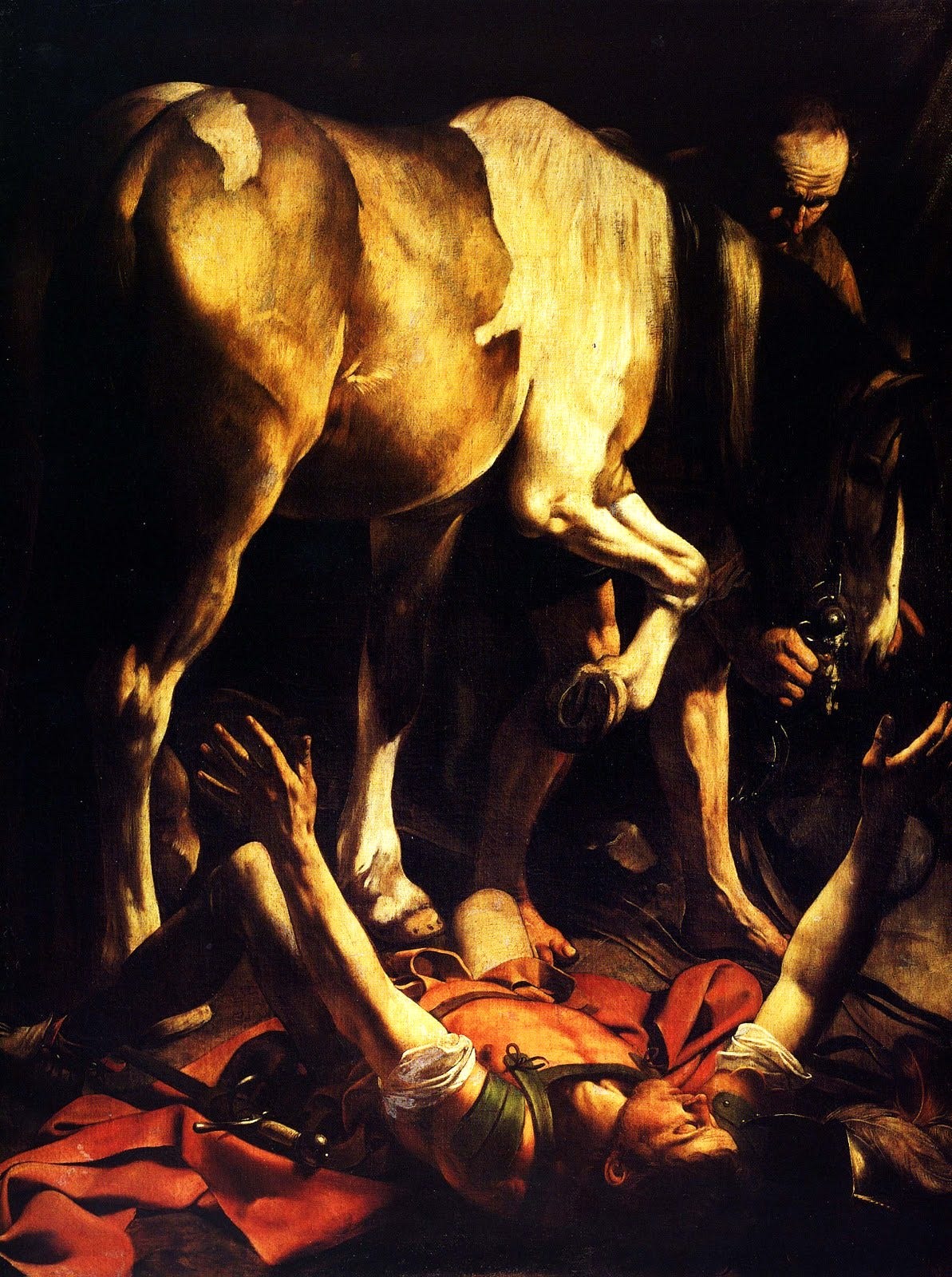

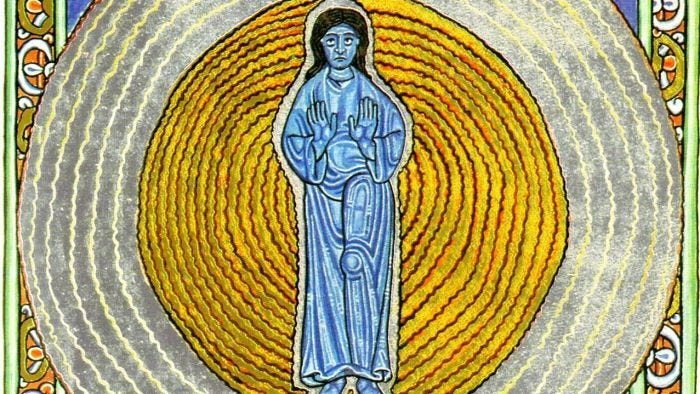

The relationship between mental health and religion is a mysterious dynamic, one that’s long fascinated humanity. In certain cultures, people with epileptic fits are thought touched by the spirit realm, their neural storms understood as pathways to the divine (I’m thinking here of the scenes of prophetic rapture in Martin Scorcese’s biopic of the Dalai Lama, Kundun.) The ancient Greeks believed their oracles inspired by the gods. Even Socrates, father of rational philosophy, claimed he was driven by an inner “daemon.” William James, of course, wrote perhaps the greatest account of psychology and mysticism with his study The Varieties of Religious Experience from 1902. There he explores the fluid line between numinous encounters and mental pathologies. Taking his cue from James, Jesuit psychologist William Meissner published a 2009 study of the founder of the Society of Jesus. In Ignatius of Loyola: The Psychology of a Saint, Meissner surveys the Basque man’s life—his extreme scrupulosity, his religious visions, his interactions with others—and entertains an astonishing conclusion: that Ignatius was very likely psychotic.

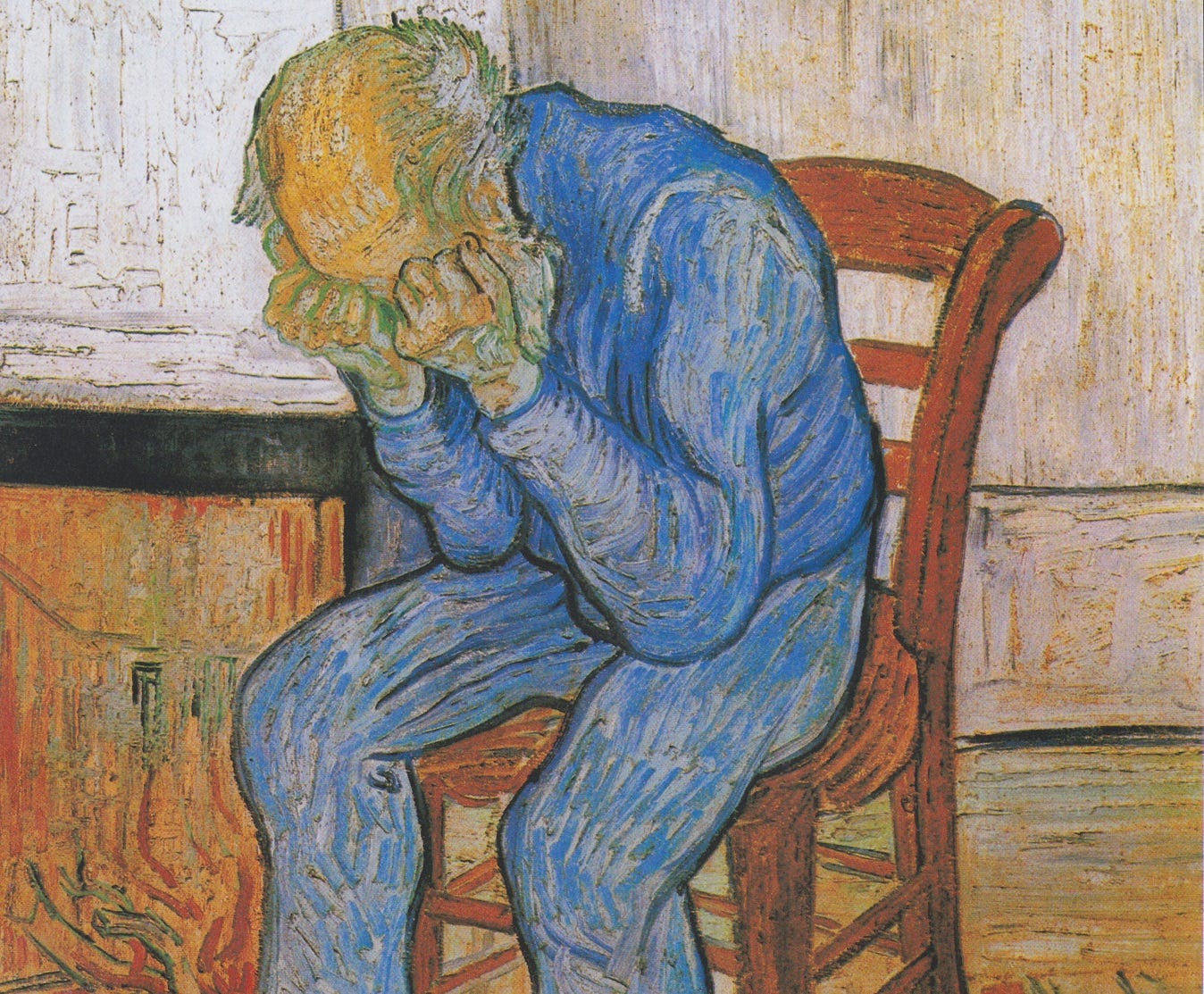

In contrast, mental illness has been stigmatized in American culture for decades, especially in religious life. Thankfully, the church and society at large are developing an appreciation not only for the prevalence of mental illness, but also for its role in the lives of spiritual seekers. Witness the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande, who was just beatified in El Salvador. The podcast AMDG featured an interview with author Cameron Bellm about Grande’s struggles with mental illness. This included at least one complete breakdown during his formation. Bellm’s latest book profiles the many saints who battled the noonday demon and other psychic afflictions. Such revelations offer an important corrective to the tendency on the part of the church to render such people as spiritual supermen and women. They were fellow sufferers, like you and I. And if they’re saints, they’re saints not in spite of their mental illness, but in part because of it—it’s their cross. In a similar, less-Christian vein, writer Ruth Ozeki speaks beautifully in a recent interview on The Ezra Klein Show of the interplay between her Zen Buddhist practice and the “voices” she hears in her mind. These mental phenomena lead both to creative output in her novels, but also to dangerous emotional territory.

Modern psychiatry is no less sure of itself when it comes to the interplay between mental illness and spirituality. I know from first-hand experience. I was in high school when the first feelings of depression enveloped me, my mind and mood weighed down by sadness and gloom. Church was always a domain in which I felt calm and comforted (my family were Catholics), an attraction to religion that expanded in college. I attended a Jesuit school, and my life was changed when I made a short version of Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises. The Ignatian method of employing the imagination to pray—conjuring yourself into the biblical scenes with Christ—captivated me. I developed an intimate relationship with Jesus for the first time, feeling drawn to him and his work for the Kingdom. Depression reared its head at times, but I managed to keep it at bay.

Immediately after graduating, I returned home to upstate New York and became involved with a charismatic prayer circle. I received the phenomenon of praying in tongues, and twice I was “slain in the Spirit”—the phrase used to describe the experience in which God’s Spirit floods your being, leading to the literal suspension of your body. As I walked up to a cluster of people praying, they extended hands over me. Instantly, I felt the sensation of floating; I didn’t even know I was falling backward, and that the people were holding me and gently placing me on the floor. I laid there for what seemed like hours, in a state of total mindfulness—freed from the thought-stream, body utterly relaxed, sensations of peace, joy, love coursing through my consciousness.

II.

These experiences of grace, though, were false indicators of what was to come. When I was 24, I made another retreat, this time at a Benedictine monastery south of Boston. The weekend was part of a course I was taking on the theology of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the 11th-century Cistercian reformer and mystic. In the course of those days, I felt the cloud of negative thoughts dissipate during my meditations. In their place, a feeling of God’s love crept in, as if I could hear the soothing voice of the Spirit. Strange events happened around me, too—other people on the retreat said and did things that I interpreted as signs from above. As I was praying in chapel one afternoon, for instance, another retreatant wordlessly dropped a piece of paper in my lap. “And what about your vocation?” he’d written on it. I stared in silence (I’d been considering joining the Jesuits or even a monastery for some time). When I approached him later, his response floored me: “That’s just something that came to me in prayer.”

As you might expect, all this did a number on my psyche. I left on a high, but a state also mixed with anxiety. It felt like God was coming right at me. After years of pleading for him to reveal his plan, I now felt overwhelmed with the feeling that I must become a vowed religious—something I was compelled to do almost against my will. This was convulsive, as I was in a long-term relationship with a woman at the time. In fact, she came to see me shortly after the retreat. I was plunged into what felt like my excruciating duty: to end the relationship with her and obey God’s will to enter religious life. And so I did. Or at least tried to. After a messy weekend, we broke up. I was crushed, but felt duty-bound to move ahead with single-minded commitment. In fact, I felt called not just to be a religious, but to be a saint. I literally thought I was a new Francis of Assisi, called to give away my possessions and wander the streets proclaiming the Gospel.

What followed was catastrophic. Over a period of five months, I rode a frightening roller coaster of emotions. These weren’t your everyday sensations of happiness and sadness. These were huge mood swings taking place over days—feelings of ecstasy and religious zealotry one day, devastating doubt, grief, and depression a few days later. I went running one day and felt so high on God I thought I would sail into the clouds. If that wasn’t enough, when I was done and stretching on a park bench, a random woman came up to me and told me that she’d just been talking to the Lord and that he’d asked her to convey how much he loved me. This is true. You might forgive me for feeling like an unseen power was intervening into my life.

As the weeks progressed, my mental state became unhinged. Intense anxiety afflicted me, manifesting itself in tightness of the chest, inability to sleep, racing thoughts, and more. I began to question my vocational decision and my faith itself, saturated with critical thoughts that seemed to chase me like harpies. Here is where things get really dicey. In the world of discernment, Christianity often construes the process as a battle between the Spirit of God and that of the “enemy,” as Ignatius put it. When someone seeks to move closer to the Lord, attracted by consolation, the enemy can fight back, stoking feelings of desolation and discouragement. According to this line of thinking, then, you should resist the bad thoughts and emotions as distractions trying to blow you off course. And yet in other places, Ignatius and the spiritual masters teach that your feelings can actually be indicators of what you—and by extension God—most deeply desire. In other words, if you feel desolate when contemplating a particular life choice, that could be a sign that such a vocation isn’t God’s will (or your own).

All of this led to confusion and a distraught condition on my part. I became increasingly unable to regulate my emotions, engage in executive functions, or cool my febrile mind. I recall struggling even to sign my name legibly, and feared I might stumble into traffic while walking the street. Finally, after a series of sleepless nights, I realized I had to get somewhere safe—home, to my family. But on the subway to the bus station, I snapped, flipping into a full-blown panic attack. Convinced I was going to die, I took a taxi to the ER and told them I was afraid for my safety. As anyone can tell you who’s been down this road, once you do that, you lose your freedom instantly. I was removed to a private room, my clothes and possessions taken from me, forced to wear a gown and subjected to cold questioning from staff and the injection of needles for blood work—not exactly the treatment you need when you’re paranoid.

I wish I could say that I turned the corner at that point. But no. Things got much worse. Through an insurance foul up, I was transported to an in-patient psychiatric facility in a different state. There I was plunged into a new circle of hell. Scared, imprisoned in this strange, alien place with fellow freaks, I encountered a patient who told me he was possessed by demons. This, as you can imagine, scared the living shit out of me. Soon I began to hear what I experienced as satanic language coming out of him as he paced the floors, assaulting my soul in the exact opposite manner that God’s Spirit had calmed me a couple years before. In my deluded state, I became convinced that I was being put through some kind of ultimate test, a battle royale meant to be the final barrier to spiritual liberation. I decided I had to confront this patient and try to exorcize the demon from him. And so I did. As he emerged from his room one night, I flew at him, yelling in charismatic tongues as I tried to drive out the dark spirit. This triggered an explosive scene of fighting, screaming, and panic. The nurses and attendants shut down the floor, separating me from the young man. Meanwhile, I felt like I had stared into the face of evil, which left me traumatized.

That was the abyss. After that, I was put on antipsychotic medication. Eventually I was released. But the road back to mental health was long. I battled depression for over a year after that. Things improved markedly in graduate school (where I studied theology, no less) what with new friends, interesting courses, and a vibrant community to support me. But since I graduated, things have been very touch and go. The depression and negative thought patterns afflict me still. In 2016, I crashed out of a doctoral program due to my anxiety. And a couple years ago, I had another breakdown and underwent two more hospitalizations. I remain on medication (the benefits of which are elusive) and maintain a regimen of mindfulness and physical exercise in order to stave off distress. I rely on the support of family, friends, and—most of all—my wife.

III.

What to make of this? I don’t know. I probably never will, until the Resurrection. The official diagnosis is bipolar II, a milder form of what used to be called manic-depressive disorder. (For an unforgettable account of bipolar I, the harsher version of the illness, I recommend An Unquiet Mind by Kay Redfield Jameson.) The psychiatrist who first gave me that label, after I came out of my hospital stay, told me that my manic episode was triggered by the retreat I’d made. He advised me to stay away from intense religious experiences. Since that prescription, other therapists and doctors have been less sure about the cause of my illness. They express more agnosticism about religious experiences, attuned to both the benefits of spirituality and the dangers it can induce. Most of them agree that religion is an important part of my identity and should not be excised. And they believe in the mental health improvement that can come from a balanced, careful application of spiritual practices. This means yes to meditation, gratitude practices, and Ignatian prayer. It means no to charismatic experiences, intense retreats, and the conservative forces in the church who rule by fear and power. (In fact, my most recent breakdown occurred after I went to a priest billed as a healer and he prayed over me precisely to heal me of bipolar).

How to read my previous religious phenomena, then? Were they legitimate? Real? Of God? Or not? There are several interpretations you could offer—which is correct? One? Several? None? Both James and Meissner conclude that the authenticity of mystical experiences rests on what fruits they produce (the same standard James applied to philosophy). If the experiences lead a person to become more integrated psychologically and active in the world, that’s a good sign that they’re of God. Many of the greatest mystics in the Christian tradition were also extremely busy, founding religious orders, reforming churches, converting society to justice. The January issue of Commonweal features an interview with Bernard McGinn, foremost scholar on mysticism, and he highlights the achievements of these dynamic people, like Teresa of Avila.

With this in mind, then, I might conclude that much of what I experienced back in 2009 was not of God. It led to my undoing rather than my flourishing. My hallucination in the hospital with the young man, for instance, was probably a true psychotic break. Other elements might have been genuine—I really felt God’s love at times—but I interpreted them in ways that led to rash decisions. (I can’t be too hard on myself here—if I had a dollar for every time in my twenties someone told me I should become a priest, I’d have more money than God.) Finally, it may have been the case that, yes, I did experience a true call (to what is unclear), but something just went horribly awry—call it mental illness or a nervous breakdown or spiritual desolation or whatever.

The field of psychiatry has, to date, failed to find any lasting treatment for mental illness. As I mentioned, most medications prove marginally effective, no better than placebos in many studies. But things could be changing. Michael Pollan’s 2018 book How to Change Your Mind investigates the growing use of psychedelics to treat afflictions, everything from alcoholism to depression. At the same time, Johann Hari wrote an intriguing book a few years ago, Lost Connections, that argues (persuasively to my mind) that our social environment is as much a cause of mental illness as biology. It’s probably a combination—as someone says in the book, your genetics load the gun, and your social situation pulls the trigger. Dr. Thomas Insel, Director of the National Institute of Mental Health, published a monograph in February making the same case.

Curiously, the effect of medicines like psilocybin on the mind is close to that of mystical experiences. Patients experience vivid visions, the death of the ego, and overwhelming emotional journeys. Such trips have the effect of revealed truth for many, leading to profound behavioral changes. For depressed people, one hit of psilocybin can relieve symptoms for months, rewiring the neural patterns of the brain that break the chain of negativity enslaving the mind. The affinity between these ecstasies and religious phenomena like near-death experiences is fascinating. I’ve yet to try psychedelics—given my past mental breaks, I must tread carefully. But I’m intrigued enough to learn more, especially because no other serious treatments are on the table.

IV.

Still, you can’t take this stuff too far. Writer Brian Muraresku published a book in 2020 arguing that psychedelics explain the origins of Christianity. Despite what I just wrote about such drugs, Muraresku is misguided here. The following of Jesus began as a way of life—of community, of solidarity, of radical egalitarianism—not a hallucinogenic state. The same principle holds for supernatural elements. Back in 2005, the radio program This American Life profiled Rev. Carlton Pearson. Pearson was a rising star in the Pentecostal church, adept at driving out the devil from his worshippers. But then he underwent a deep conversion and stopped believing in hell. He changed his life completely, losing his megachurch and instead ministering to social outcasts in the storefront of a strip mall. As for his battles with evil, Pearson looks back on them with skepticism. If you go looking for that kind of thing, he explains, you will find it. But it’s not the heart of the Gospel.

Today, I remain a Christian (an Episcopalian now) despite my traumatic experiences. Perhaps that’s unwise—I’m attuned to the dangers of religious affiliation. But I’m much more invested in the social implications of the faith, the call to help build the world into the kind of just community God intends for creation. My prayer life is meager and infrequent, and I no longer try to discern God’s will. I am highly dubious of any mystical dimension to the faith. Christianity is primarily an everyday religion—it eschews esoteric elements and casts doubt on claims to personalized supernatural connections. Christ calls Christians—and all people of good will—to practice corporeal discipleship.

This means working for the Kingdom of God in the world: visiting the elderly, accompanying poor children, writing to inmates. And seeking the transformation of society into an order where, as Mary says in the Gospel of Luke, the mighty are cast down and the lowly lifted up. Praying and laboring for such a vision to become reality is infinitely more important to the spiritual life than any mysticism. Not that they’re inherently opposed. I think of Abraham Joshua Heschel, the great Jewish mystic, walking with Dr. King in civil rights protests. But to paraphrase Paul of Tarsus—no stranger to ecstasies himself—if I have all manner of mystical visions but do not have love, I am nothing.

I began this piece noting how many traditions ascribe a divine origin to mental illness. But Christianity, it’s important to note, doesn’t. In the Gospels, the crowds never relate to the mentally ill as inspired by God. Jesus certainly doesn’t. Quite the opposite. He treats them like he does people suffering from physical ailments, and heals them with his curative power. Jesus himself experiences mystical rapture, as at the Transfiguration. And, in fact, some claim he’s lost his mind—perhaps even his own family. But Christ’s in a different category from us, being the Incarnate Word of God.

Contemplating the story of the Gerasene “demoniac” the other night, I was struck again by its uncanny portrayal of mental disorder. The man lives among caves, bruising himself on the stones, cut off from the community. Jesus responds to him with compassion, salving his psychic wounds and leaving the man, as the text says, in his right mind. This is one thing I’m certain of: God desires the healing of all afflicted with these debilitating disorders. And there are more than ever, what with the pandemic wreaking havoc on our collective well-being. If I pray for anything these days, it’s this: that you, that I, may be put in our right mind.

I am impressed with your deep knowledge of Ignatius. But have you heard of Boethius? I believe you would take solace in his story.