I. Boston Strangler - On the Brink

Dropping in time for St. Patrick’s Day, Matt Ruskin’s Boston Strangler (on Hulu) chronicles the years in the 1960s when the Irish/Italian-controlled city was brought to its knees by the rape and murder of thirteen women, carried out in a gruesome manner and marked by a unique signature: stockings knotted around the victim’s throat. The movie, which Ruskin also wrote, deploys two plots. The primary one follows Loretta McLaughlin (Keira Knightley), a reporter at The Boston Record American, as she breaks the story and hunts for the killer alongside her partner, Jean Cole (Carrie Coon). The secondary one explores how the two journalists butt heads against the male-chauvinist culture of the newsroom, police department, and domestic sphere, leading to mixed, complicated results. The two narratives inform each other as the film unfolds, with the domination and degradation of the female victims at the hands of a sociopath—and the complacency of the justice system—becoming a symbol of women’s stifled status in the pre (now post) Roe world.

By combining the psycho-killer and newspaper genres, and putting them at the service of a social-problem picture, Boston Strangler works in a mode akin to last year’s She Said. But where that movie foundered (full review here), Ruskin’s picture arrests your attention from start to finish. Taking their cue from David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), the director and his cinematographer, Ben Kutchins, create a gloomy, desaturated visual ambience. The muted greens and yellows—along with the low-angled shots, aerial cameras, and sepia tones—lend the picture the desired noir quality and conjure a mood of urban alienation. The costume and set designers do a striking job at bringing a dyed-in-the-wool look to characters and their haunts. And Ruskin’s penned a strong script that hues to the narrative with clarity and a command of the various conventions in play. The problem isn’t what the film does—it’s what it stops short of doing.

The story opens in 1965 with the murder of a woman in Ann Arbor, Michigan at her flat. It then doubles back three years earlier to Boston, where McLaughlin—married with kids—works at the paper reviewing consumer products. Bored with her beat, she takes an interest in the sexual assault and strangulation of three older women in the area. While each has been reported in local papers, no one has brought the incidents together. She begs her editor, Jack Maclaine (Chris Cooper), to let her investigate, which he reluctantly allows after she agrees to do it on her own time. Her husband, James (Morgan Spector), supports her at first, and when she publishes a story that attributes the murders to a serial killer, it’s a bombshell.

The police commissioner (Bill Camp) marches down to the paper’s office and tells Maclaine that McLaughlin got her facts wrong, but when she provides proof—and a fourth victim turns up—the case explodes. Maclaine assigns Cole to work with Loretta, and her colleague’s brassy independence both impresses and threatens McLaughlin. Jean shows her how to use her femininity to her advantage and play the powerful men that surround them. The pair allows the paper to take glossy photo shoots of them as a marketing ploy—two attractive women reporting on the rape and killing of more women. In this way, the movie hints at how the true-crime industry trades on the salacious aspects of its content to titillate its fans.

But as the stress of the investigation strains their marriages, and anonymous threats pour in, Loretta and Jean struggle to navigate the precarious freedom and power they’ve accrued. Meanwhile, the story metastasizes as the cops’ ineptitude and delays riddle the case. Loretta turns her typewriter against the department, causing her editors to stonewall her all the more. She subsequently develops a source in one Detective Conley (Alessandro Nivola), providing him with leads in exchange for inside info. Conley’s overwhelmed by tips, but every trail finds a dead end. The case turns in ‘63 when a seventh victim—this time a young woman—is slain, breaking the pattern.

At that point, Loretta begins to fear either that the killer’s escalated or—worse—spawned a copycat. Terror descends on the city, with authorities instructing residents not to admit anyone in their dwellings they don’t know. But the bodies keep piling up, the murderer striking at will. McLaughlin, moved by her encounters with the victims’ kin, becomes fixated, working long hours and neglecting her family. And when a detective from New York phones her with news of a murder in his district whose crime scene bears the same decoration, she’s thrust down a rabbit hole that grows progressively serpentine and personal.

The casting of the film is sensational, with everyone from the headliners to bit players grooving on the same ace frequency. Ruskin establishes the hard-boiled character of the reporters; unlike in She Said, the movie doesn’t exploit the audience’s sympathy for its protagonists as cover for a poor script. McLaughlin and Cole are tough pros who carry themselves well and brook no bullshit. Coon, Cooper, and Nivola inhabit the skins of their characters with layered authenticity, avoiding caricature, and even the supporting actors—like Camp, Robert John Burke (as the paper’s chief editor), and the many local players—leave distinct impressions in your mind. And in Knightley, Ruskin has one of our most intelligent and quick-silver actresses at his disposal, who turns in a tight, focused performance.

If only he’d given them more to do. With such a crack ensemble on screen, you watch in disappointment as the movie pulls back from developing the characters and deepening its themes. Cooper, in particular, is wasted on staid one-liners, and Nivola’s Conley lacks a personal dimension, despite the fact that he’s so shaken by the case that he quits the force and becomes a consultant on a ripped-from-the-headlines movie. The same goes for Coon, with Ruskin giving us only a brief encounter between Cole and her husband. We see the outlines of a bond between her and Loretta, but their bar scenes are attenuated—Ruskin doesn’t unpack the newfound sisterhood the reporters create.

Likewise with McLaughlin’s marriage: the film traces its arc from stability to estrangement, but the script doesn’t fill in the gaps. Spousal feuding and conflict don’t appear, baffling given the quality of the actors on hand. As a result, Knightley takes on a one-note quality after a while; we get just a hint of the charisma and depths beneath her buttoned-down persona. In her seriousness and drive, Loretta calls to mind DSU Jane Tennison from the procedural drama Prime Suspect (1991-2006). Knightley has the chops to match Helen Mirren’s riveting, complex performance; that she doesn’t get to show them off is a let down.

With the picture racing to come in under two hours, it feels as if Ruskin doesn’t realize the alchemy he’s got going. Given the caliber of the acting and design—and his own taut direction—he might easily have added another half hour to mine the well. In doing so, he could’ve transcended the genre, expanding the scope from the crime content to paint a portrait of an entire society at mid-century. But these stones go unturned, and you’re left frustrated. The Boston Strangler inaugurated an era of high-profile serial killers, and you desire a greater sense from the picture of the link between the random murders and the collapse of social ties in the postwar era.

Likewise, you crave more macabre horror from the psycho and a personal connection with his victims, who blend together vaguely. The movie doesn’t explore the rivalries between the city’s dailies, nor take in the full tribal nature of Boston’s enclaves and ossified institutions (the way 2015’s Spotlight does). Despite having all the makings of greatness, it balks at going for the depth and breadth of Anthony Lukas’s epic non-fiction novel Common Ground (1985), which examines the city during the same period.

Ruskin also fails to deepen the theme of indiscriminate male power, the vulnerable position women of the time occupied at every strata. He doesn’t put McLaughlin in enough danger, and when he does, it’s too little too late. Likewise, he ignores the extent to which Cole and McLaughlin pioneer a new type of American female: not just a working woman, but one who eschews male guardianship entirely. For a movie that puts female characters at the center, it displays a curious lack of interest in their inner lives. It moves too quickly over narrative complexities—like how defense lawyer F. Lee Bailey (a brief Luke Kirby) intervened to poison the proceedings—and doesn’t process a critical error by its protagonist.

Most of all, it refrains from weighing the cost of obsession: how the story broke everyone who touched it, and the way it consumed McLaughlin over the years, much how John Travolta’s Jan Schlictmann is destroyed by his compulsive hunt in the excellent legal drama A Civil Action (1998). It feels odd to knock a movie for limiting itself, and these gripes arise precisely from what it does well. Ruskin’s made a good film. But as with the case of the Strangler itself, you come away feeling that those in charge failed to do the story justice.

II. The Quiet Girl - Celtic Heartbeat

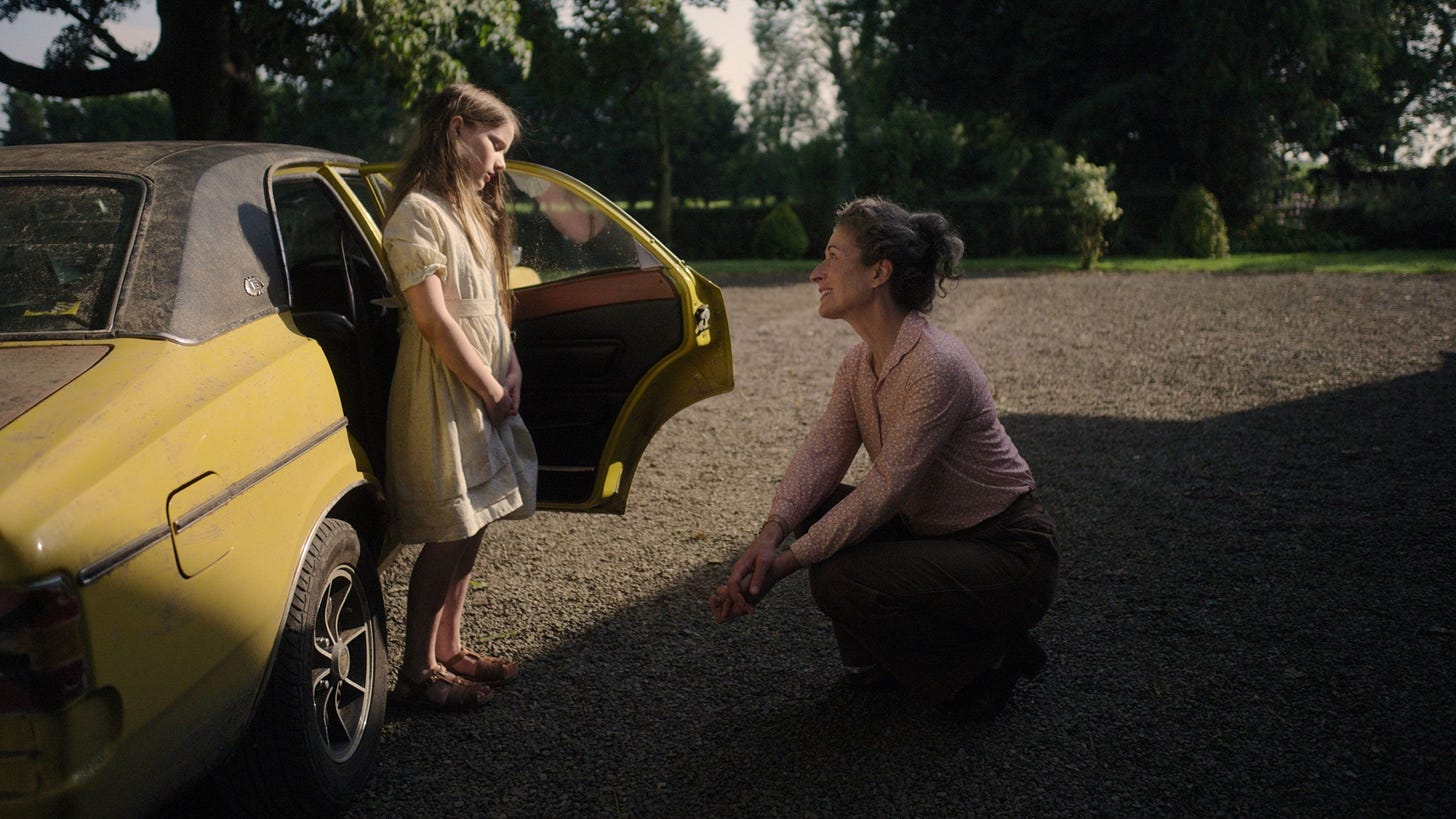

The Irish are also the focus of The Quiet Girl, a small coming-of-age film from last year written and directed by Colm Bairéad (his first feature). The picture was nominated for an Oscar in the International category, and it’s a crime it didn’t win. After seeing it over the weekend, it instantly leapt onto my Top Ten list, prompting a revision. Bairéad adapted it from the 2010 novella Foster, by Claire Keegan, and it tells the simple story of a young girl, Cáit, whose poor-trash parents send her for a homestay with an older couple on their farm. Her mother’s bringing yet another pregnancy to term, adding to their large, bedraggled brood, and the sleep-away will offer everyone relief. As the title suggests, Cáit’s meek and taciturn, made almost mute by the caustic atmosphere in her home. Between her unhappy parents and regimented school, she has no room to breathe and acts out by running away and hiding for stretches.

But with a change of environment—and some paternal affection from Eibhlín (Carrie Crowley) and Seán (Andrew Bennett)—the lass begins to find her voice. Like the audience, Eibhlín falls for her immediately, tendering the girl both love (she brushes her hair one hundred times at a stretch, counting each stroke) and respect, asking Cáit’s opinion on her needs and desires. The girl’s never experienced such mutuality before, and—slowly, hesitantly—comes out of her shell. Her caregivers find their footing, too, and we see the small adjustments and growing pains they all go through. Seán is stand-offish at first, curiously to Cáit, and he’s not sure what to do with her as she helps him with chores. When she runs off again, he barks at her, confused. But beneath his reserve lies buried, unspoken care—the next morning, he silently leaves her a cookie as she breakfasts. He encourages her energetic bursts, timing her as the filly sprints to the mailbox and back. Bairéad shoots these images in slow motion, lingering on Cáit’s joyous taste of physical freedom.

Bairéad builds the movie in a hushed, soft manner that befits the soul of its protagonist. Appropriately, he films it from the girl’s point of view, capturing the way the world looks to a child trying to make sense of adults and their moods. Their faces are often cut off in the frame, conversations oblique and indistinct, the way they sound to kids. Unlike other attempts of late, the movie keeps narrative clarity without much dialogue, telling the story visually and cued in to the slightest emotion and response. It charts the contours of Cáit’s felt experience, watching as she hopes against hope that she matters to someone. Gradually, she learns of the grief that her foster parents carry and the hole she fills for them.

The director coaxes a gentle performance from Catherine Clinch, whose impassive face works for a character who’s been repressed by her embittered father. It’s Crowley, though, who makes for the soul of the movie. You respond to Eibhlín with complete warmth, her eyes wide and liquid. It’s a performance imbued with grace. Except for the Russians, I can’t think of another people who pair the beauty and cruelty of life in quite the same way as the Irish. Bairéad does so here, through the lyrical employment of Gaelic and a luminous scene that Cáit and Seán share on a beach in the moonlight. Like a Celtic ballad, The Quiet Girl draws an image of a delicate heroine that slays you in your step.

Can't wait to watch them.