Lincoln's Dilemma: Introduction

History Gone Wrong

Several years ago, I found myself in a restaurant with my wife discussing Ron Chernow’s exhaustive biography of Ulysses Grant (as one does). The couple at the adjoining table overheard our conversation, and the husband interjected with enthusiasm. He was a history buff himself, he said, and looked forward to reading about the Union’s greatest general. Then he leaned over and, in a voice I’ll never forget, whispered: “You know, a lot of people don’t understand that the Civil War wasn’t about slavery.” We were sitting in Boston, the cradle of abolitionism—not the Deep South. To his credit, when I corrected him that the war was absolutely about slavery, he reacted with genuine surprise and pledged to do more research. Chernow’s book, I said, would be a good place to start.

The new documentary Lincoln’s Dilemma would not. Produced by AppleTV and released on President’s Day weekend, the series masquerades as a film about the 16th President. In reality, it’s ideological disinformation that distorts the man’s legacy and that of the entire antislavery movement. To be fair, it has its virtues. It attacks the fallacies of the Lost Cause head on—always a boon. It puts slavery at the center of the Civil War, where it belongs, and takes dead aim at Confederate deniers. In so doing, it corrects the famous Ken Burns’s saga from 1990. Burns’s treatment is looked on as Gospel by many, but it indulges in the very romanticization of the war—and the South—that have misled millions. But while it remedies these errors, Lincoln’s Dilemma asserts a new set of biases. It bills itself as an objective treatment that seeks to expand our understanding of how American slavery was destroyed. Instead, it twists the record of the past to serve its own dogmas. While claiming merely to deconstruct the mythology of the Great Emancipator, it in fact disseminates a false mythology of its own. This isn’t history—this is propaganda. (If you want to watch a fairer treatment of Lincoln—albeit with cringe-inducing dramatizations—check out the new documentary on the History Channel.)

On the plus side, Barak Goodman and Jacqueline Olive—the writers and directors of the new series—interview nearly every major historian in the field. The lineup is impressive: James McPherson, Sean Wilentz, and Eric Foner—the Triumvirate of Civil War deans. James Oakes, Steven Hahn, and Ed Ayers, right behind them. It also showcases many Black scholars who’ve received less notoriety than their white peers, like Christopher Bonner, Kellie Carter Jackson, and Edna Greene Medford. Rounding out the talking heads are Jelani Cobb of The New Yorker and Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative. Still, there are notable absences. Gregory Downs, author of the essential volume After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War, isn’t interviewed, nor is Elizabeth Varon or Heather Cox Richardson. Drew Gilpin Faust and Stephanie McCurry, who’ve published works on the Confederacy and women in the war that revolutionized the field, are absent. So is Allen Guelzo. And David Blight, writer of the definitive biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, doesn’t appear.

Given the number of contributors, the series is woefully short. The Civil War era is the most complex period of the United States. Wilentz calls it perhaps the greatest story in modern history. To do it justice, you have to take the necessary time. Yet instead of giving the subject the deliberate, comprehensive, nuanced treatment it deserves, the filmmakers compress the event into four short episodes. This results in a frustrating experience, as it dispatches huge topics in seconds. Erudite scholars are reduced to soundbites. Matt Karp, for example, who wrote an important book on the foreign policy aspirations of slave owners, has a total of two lines. Michael Burlingame—the repository of more Lincoln knowledge than anyone alive—gets in just a few points. With such a star-studded cast, the series should’ve been ten times as long.

But the problem with this film isn’t just its brevity—it’s its argument. The show purports to offer a realistic treatment of its subject, dismantling the hagiography of Lincoln by presenting him as a complicated figure who—rather than born, like Moses, to free the slaves—evolved a historical consciousness of the need to destroy slavery and his role in that effort. This is true, and we are better served by reality than myths. Yet while claiming otherwise, the documentary falls short of a full account of the antislavery movement. It took me hours to wade through the film because I had to stop every few seconds to catalog its errors, inaccuracies, and misreadings. In its zeal to strip Lincoln of his laurels, the series omits crucial information, warps certain facts, and collapses important distinctions. It’s rife with uncharitable readings, blinkered interpretations, and unfair characterizations. It engages in opportunistic attacks, fails to provide context, and allows brazen half-truths to go unchallenged. Every generation revises history; it’s impossible to render the past objectively. But there’s a difference between interpretation and perversion.

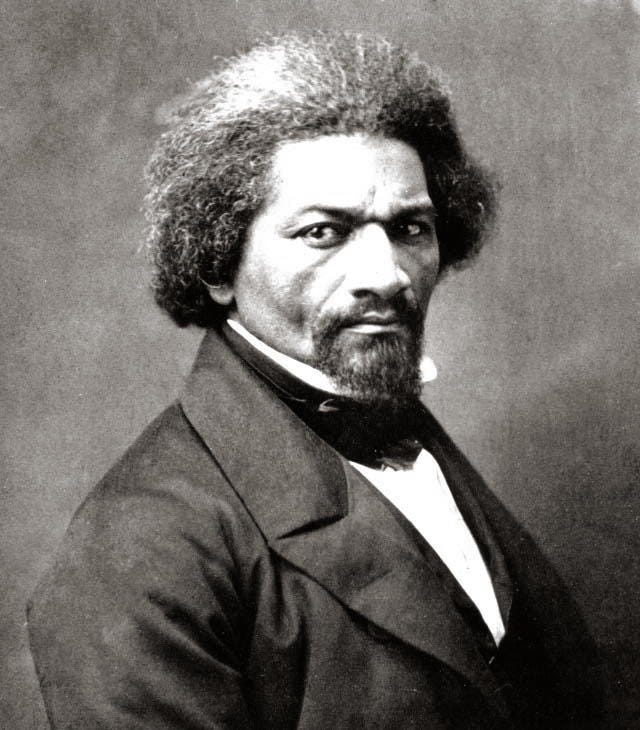

The film’s overall thesis is that the abolition of slavery was the work of more than one man—Lincoln didn’t end the institution with the stroke of his pen. It seeks to highlight neglected voices, particularly those of Black Americans, who played indispensable roles in the struggle for freedom and the nation. This is heartily welcomed. But instead of deepening our appreciation of the intricate ways abolition came about (see Oakes’s The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution and The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition by Manisha Sinha), the series simplifies matters in another direction. It asserts that Lincoln never set out to end slavery at all and that it took the work of Black activists to convince him. It paints him as slow to emancipation, a moderate squish who (while believing slavery was wrong) didn’t care enough about Black Americans to take harsh measures against it. Only through war, suffering, and pressure from radicals like Frederick Douglass did his heart expand so as to see the necessity of striking at slavery directly.

While this argument may confirm the bias of its liberal audience, it’s factually wrong. Lincoln’s dilemma wasn’t whether to abolish slavery. It was how. And too often, the series (while claiming the opposite) frames issues in terms of either-or, not both-and. Either Lincoln freed the slaves, or the enslaved did it themselves. If we credit the Union Army and Navy with a major role, it somehow takes away from the agency of Black people (even though Blacks served in uniform). If we elevate Douglass, it must come at Lincoln’s expense. Zero-sum. In calling out the Lost Cause narrative, and celebrating the role of free and enslaved Blacks, Lincoln’s Dilemma takes positive steps. At the same time, it over-corrects in important, telling ways.

And that’s because the film’s really an extension of the 1619 Project of The New York Times. In this narrative, Black people fought slavery and racism mostly alone. Lincoln never intended to end slavery; the only mention of him in the entire Project is a jaundiced account of one meeting he had with Black leaders. The Project has been eviscerated in places like the World Socialist Website. But Lincoln’s Dilemma carries water for its regnant ideology. Hence why the film neglects figures like Theodore Parker, William Cooper Nell, and John Brown; Robert Gould Shaw, Thaddeus Stevens, and Ulysses Grant.

In the case of Brown, Shaw, and Grant, they led Black and white forces in a violent attack against the Slave Power. At the head of that assault was Lincoln, who (like Brown and Shaw) gave his life in the effort. But to acknowledge that the American Revolution gave birth to a biracial antislavery movement—the first in the world—let alone that there were white people who fought and died alongside Blacks for freedom and equality during the Second American Revolution, would collapse the argument of the film.

What’s astounding in all this is that the series enlists the contributions of three historians who’ve publicly opposed the 1619 Project—Wilentz, Oakes, and McPherson. I’m sure they had know idea they were being impressed into service for a narrative they’ve denounced. (Check out Oakes’s recent essay in Catalyst, where he dismantles the Project, as well as Karp’s essay in Harper’s.) The contributions they make are sound, but they’re subverted by other scholars. This leads to a sense of internal struggle in the film. And the editorial decisions of the directors are clearly against them. The movie takes the authority of anti-1619 scholars and uses it to underwrite the very Orwellian historical reading they’ve opposed. They must be outraged by what’s been done using their imprimatur. Over the next few posts, I’ll take you through each episode and attempt to explain what the documentary gets right and where it goes wrong.