The first episode of Lincoln’s Dilemma sets up a dubious frame. It opens with images of the January 6th assault on the U.S. Capitol in 2021 and leads with a quote from Bryan Stevenson that Lincoln’s presidency, while ending slavery, failed to address underlying issues that plague us today. Stevenson’s done extraordinary work as a lawyer for the poor. But he’s not a historian, so I’m unsure by what authority he makes his claims. In any case, by “underlying issues,” I assume he means the ongoing racial tension in the United States, which reared its ugly head during the Trump administration. But how can this be a failure of Lincoln’s? The reason he didn’t address issues of racial equality was that he was shot and killed before he had a chance to do so. Any school child could tell you that. The Civil War was just coming to a close when he was assassinated, leaving the thorny issues of civil rights and equality to his successors. Right at the outset, then, the documentary draws a false, conspiratorial line from Lincoln to our present racial difficulties.

The film follows this statement with one by Jelani Cobb in which he says that if Americans think of the Civil War at all, it’s generally portrayed as Lincoln freeing the slaves, not enslaved people helping him save the Union. “There’s been almost no conversation about that,” he insists. My question is, conversation by whom? On the contrary, the past fifty years of historical scholarship have been devoted precisely to broadening our understanding of the many people responsible for abolishing slavery—including enlsaved men and women and the free Black community of the North. Maybe the public conversation continues to reduce the story to that of Lincoln freeing the slaves by himself, but that’s a failure of education, not research.

And even here, anecdotal evidence—conversations with friends, acquaintances, and strangers—tells me that most people still don’t understand the basic fact that the Civil War was fought about slavery. The Pew Research Center confirmed this in a 2011 survey, which found that nearly half of Americans still believe the South fought for states’ rights. The Lost Cause was so successful that even most Black Americans don’t study the Civil War, as Ta-Nehisi Coates detailed in The Atlantic. Meanwhile, libertarians like Ron Paul and Andrew Napolitano spread pernicious, noxious lies that Lincoln started the war (not, you know, the Confederates who fired on Fort Sumter) and was a tyrant for suspending habeus corpus. And most liberals share the cynicism of Lincoln’s Dilemma—that Lincoln was a secret racist who just wanted to keep the country together and issued the Emancipation Proclamation out of military necessity, not as a humanitarian decree. So when Cobb makes this statement, I don’t know who he’s referring to.

But the most troubling claim comes next. Kellie Carter Jackson asserts that Lincoln “wanted to be the great unifier, to bring the country back together. He did not start his presidency to be the Great Emancipator.” This argument sets the tone for the entire documentary, and it’s woefully inaccurate. Moreover, it’s part of the film’s failure to present a full picture of Lincoln—his biography, character, and political beliefs. It begins, first, in 1861 with the Illinois politician heading to Washington, D.C., after being elected President. Already, then, the show does us a disservice. To keep events straight in your head, you really need to start with Lincoln’s youth and the first part of his career. Instead, the film scrambles the chronology, leaving you confused. When it does go back to describe his personal history, it twists the subject. First of all, Cobb says that Lincoln came from “humble origins,” stating that he had many advantages that Frederick Douglass didn’t. Of course this is correct on a basic level—Lincoln was not a slave, Douglass was. Lincoln was never beaten or sold or forced to flee for freedom and human dignity.

Yet let’s not push the difference too far. Lincoln’s origins weren’t just humble. He was dirt poor. He was born in a shack in the forest that his father built, a dilapidated building with no floor. His mother died early in his life, along with his sister. A kindly stepmother helped raise him and encouraged his reading abilities. But he had to gain his literacy on his own, a practice his father criticized. They owned few books and he had to steal time to read in between plowing rows in the fields. His formal schooling amounted to less than a year. His father would routinely hire him out to do hard labor for other farmers, a practice Abraham detested. In fact, it was this experience of working without wages that Lincoln later credited with helping him sympathize with slaves like Douglass. So why does Cobb insist on setting the two men in opposition, a kind of negative comparison? They themselves saw their stories as more in common than not—why can’t we?

It gets worse. The film claims that Lincoln was “a son of the South,” who harbored “southern sensibilities,” somehow tying him to slavery. This is wrong. Lincoln wasn’t a southerner. While born in Kentucky, his family left for the free states because of slavery. And though his wife was from a slaveholding family, that means nothing. Who among us shares the views of our in-laws just because we married their son or daughter? Many Northerners were tied to the South by marriage and other entanglements, but that doesn’t mean the endorsed slavery. The opposite, in many cases. The fact is that Lincoln much preferred the free labor system of the North. The show quotes him as saying that the sight he had as a youth of enslaved people was “a continual torment” to him. As an adult, he denounced slavery as a “monstrous injustice” and said he hated it—a word he rarely used. While he empathized at times with slaveholders, he sympathized overwhelmingly with the enslaved.

Yes, as a politician, he denied Black political and social equality in a few instances. But he made these statements reluctantly, in subservive terms, and only under pressure from his rival, Stephen Douglas. He spent the bulk of his energy attacking slavery with powerful, multifacted arguments and trumpeting the natural equality of Blacks and whites under the Declaration of Independence. In fact, in his new book The Black Man’s President, biographer Michael Burlingame calls Lincoln a racial egalitarian at heart. Though it interviews Burlingame, the film doesn’t let him say this. Douglass himself called Lincoln “emphatically the black man’s president,” in a eulogy after the President’s death. (Check out Burlingame’s interview with James Oakes below.)

Next, let’s look at his politics. In a late episode, a scholar claims that Lincoln was a radical in principle, but often muffled it for strategic purposes. This is debatable. It may have been true in his early days as a member of the Whigs. But even then, he was what we’d call a progressive—he believed in using the government to create economic opportunities through infrastructure, egalitarian banking policies, and land grants to farmers. By the 1850s, the Whigs were dying and Lincoln had grown even bolder. An admirer of Thomas Paine, he was an extreme democrat, both on economics and politics. The film passes over his ties to revolutionaries, like the German emigrés of 1848 (many of whom, like Carl Schurz, he commissioned as officers during the war). Or to socialists such as Charles Dana, whom he made Assistant Secretary of War. For years, Lincoln read a weekly column in The New York Tribune by Karl Marx—yes, that Karl Marx. Lincoln was never a full-blown socialist, but he had revolutionary ideas and endorsed the struggle of workers as part of the movement for labor rights. (John Nichols details all of this in his succinct volume, The “S” Word: A Short History of American Tradition…Socialism, as does Robin Blackburn in “Lincoln and Marx,” from Jacobin.)

When it came to bondage, Lincoln was a strong antislavery politician, viewing the movement—as most Northerners did—as part of a broad struggle against oppression: from slavers, monarchs, and capitalists. As David Blight writes in his biography, Douglass, while wishing for a fiery candidate like Charles Sumner, supported Lincoln in 1860 because he saw him as sufficiently militant. The show mentions none of this. Instead, it leaves in a claim by Christopher Bonner than Lincoln “hoped” slavery would die out and that the country would put it on the road to “ultimate” extinction. This twists Lincoln’s words, making him sound like a passive observer of slavery’s demise, merely standing on the sidelines and wishing for the institution to magically disappear. This is wrong. Lincoln didn’t just hope for slavery’s demise—he actively worked to make it happen.

For years, starting in 1854, he threw himself into building the Republican Party, a new party who’s number one goal was to end slavery in the United States. As Eric Foner relates in his 2010 volume The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, from the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act onward, Lincoln’s raison d’etre—his north star—was to build an antislavery coalition, win the Federal government, and use its authority to turn the nation away from the Slave Power toward abolition. As the film emphasizes, he accepted the view that the Constitution didn’t give the national government power to abolish slavery in states where it already existed. But the episode doesn’t explain the strategy that he and other Republican politicians developed for the peaceful eradication of slavery.

This was the “Freedom National” plan that James Oakes details in Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865. Oakes’s 2014 book completely changed the conventional wisdom of Lincoln and the Republicans. Rather than start in 1861 with the war, he traced their antislavery positions back to the early 1850s. Because (they believed) the Constitution did not give the Federal government power to abolish slavery in the states where it existed, a group of politicians (men like Salmon Chase, Thaddeus Stevens, Sumner, and Joshua Giddings) developed proposals designed to get slavery to die indirectly. Step one: build an antislavery coalition and win power in Washington, ousting the pro-slavery regime of previous decades. Step two: use that power to cut off slavery’s expansion. This would involve banning slavery in the western territories, abolishing it in the District of Columbia, and outlawing it on the high seas—anywhere the Constitution was sovereign. This would create a “cordon of freedom” around the slave states that would precipitate the collapse of slavery. How?

Oakes followed up with a separate book, The Scorpion’s Sting, about this theory. Essentially, it was this: Because of its poor farming practices, slavery needed to move into virgin soil in order to survive. If you choked off the South, then, the region would experience an economic collapse, forcing slave holders to abolish the institution state-by-state—the same way it had been eradicated in the North. The Federal government would aid this process by enticing the border states—the slave states of the Upper South—to abolish slavery. Such carrots would include incentives like compensation for owners, gradual emancipation (as several northern states had done), and a voluntary plan to resettle the formerly enslaved abroad—in Africa or the Caribbean. Once the Upper South fell, abolition would roll downhill like a wave.

The platform was convoluted, which frustrated activists like Douglass who wanted immediate abolition by direct Federal law, without compensation. And the proposal to send freed peoples overseas struck him (and us) as anathema. Blacks wanted and were entitled to the same rights and freedom on U.S. soil as whites, he said. (Lincoln agreed in principle, but he thought whites were so racist that they would never let Blacks enjoy their rights in the United States. Hence why he favored an option to let freed people settle elsewhere.) Douglass argued stridently with Republicans on these points. Their response was that while imperfect, this plan—including colonization–-could convince enough slaveholders to give up their human property, which was the greater good. In other words, abolitionists and anti-slavery politicians like Lincoln were united—if not in method, than in goal. (For a thorough summary of the antislavery political movement, read “Slavery Was Defeated by Mass Politics,” by Jacobin’s Matt Karp.)

In fact, Douglass came around from the absolutist position of his mentor, William Lloyd Garrison, to see the value of engaging in political action. He was willing to ally with white leaders who, while perhaps not morally or politically pure, agreed with him nine times out of ten—and who shared a common foe. One of those people was Lincoln. Bonner claims that Garrison and Lincoln understood each other as “tremendously” different. But Garrison sang a much different tune by 1865, praising Lincoln for destroying slavery. And when it came to Douglass and Lincoln, the two men understood that they had much more in common than not. Oakes puts it well in the show: through their own journeys, they converged on a shared strategy.

Some scholars claim that the Freedom National plan would never have worked. But Oakes believes otherwise. You know who agreed with him? The white South. Whether it would have worked on not, the slaveocracy felt so threatened by the plan of Lincoln and the Republicans that when he was elected in 1860, they rose in rebellion. The Republican platform was the first political attempt to end slavery in the nation’s history, and it terrified them. The slaveholders took Lincoln at his word when he said he wanted to put their entire way of life on the road to extinction. To deny him this power, they tried to create a new nation dedicated explicitly to racial slavery. But Lincoln’s Dilemma barely touches on any of this. It makes no mention of the Freedom National plan, or any of the Republican politicians.

And when it focuses its attention on slavery, the film again distorts the record. It cuts to the Middle Passage but leaves out any mention of the fact that slavery was practiced within Africa itself prior to the arrival of Europeans (slavery, in fact, has been an ubiquitous practice around the world). It underscores how the enslaved people were the first abolitionists, resisting and fighting for freedom from the beginning. This is true, and we must bear this in mind. But the show fails to mention the birth of the antislavery movement after the American Revolution. This was a biracial undertaking from the beginning, started by Quakers in Pennsylvania. And it leaves out any discussion of the class dynamics of slavery and abolitionism. It fixates on the physical brutality of slavery, not the economic aspect—the fact that slavery is, at heart, a system of exploitative labor. (For an analysis of how antislavery and anti-capitalism should go together, read Foner’s interview with Jacobin and Oakes’s piece, “Slavery Is Theft,” in the same.)

The abolitionists emphasized this evil as much as the human cruelty. It’s important that we do the same, because it links opposition to chattel slavery to opposition to wage slavery. In other words, opposing slavery is why we, today, should oppose capitalism—working for wages and working for nothing are both forms of exploitation under a perverse capitalist ideology. The abolitionists believed this and so should we. But today’s liberals don’t prioritize the economic interests of people, Black or white. They’re obsessed, instead, with a quasi-religious ideology that emphasizes white guilt and emotional atonement—identity politics over class politics. Hence the focus by Robin DiAngelo (and this documentary) on the moral and physical evils slavery and racism—they want to get the audience to feel bad and repent in dust and ashes, not take political actions to undercut capitalism and create a society that would benefit poor people—Black and white—on a material level.

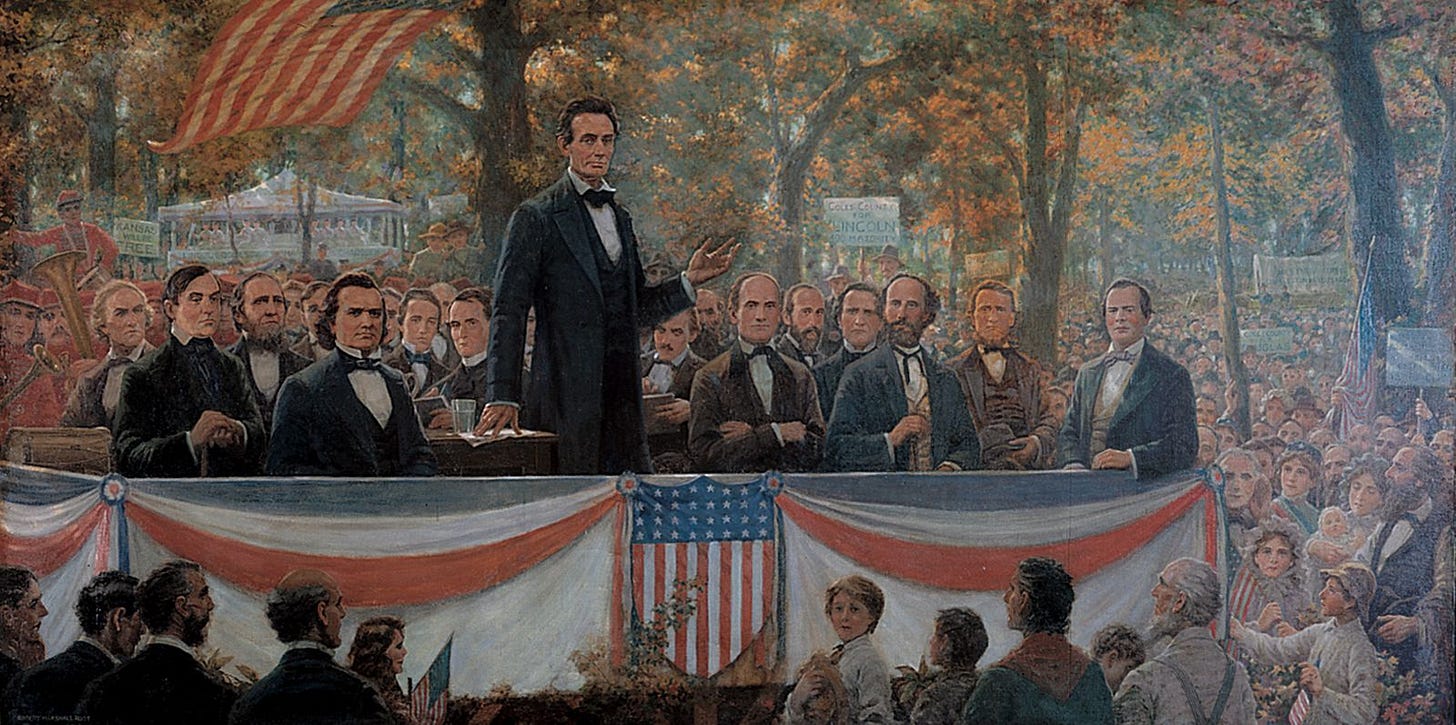

Incredibly, the episode skips over the major political events of the 1850s—it leaps from 1854 to 1858. It doesn’t explain why the Kansas-Nebraska Act of Stephen Douglas was so inflammatory, for example. It omits the caning of Sumner by the pro-slavery Preston Brooks on the floor of the Senate in 1866, an outrage that inflamed the North. There’s no mention of the Dred Scott case in 1857, a Supreme Court decision that declared the entire Republican platform unconstitutional. Lincoln’s response? He told the Court essentially to go to hell and pressed forward with his plan anyway. The episode does a better job with the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, giving Lincoln credit for mounting a rhetorically, legally, and logically brilliant attack on slavery. But it omits John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859, which galvanized the North.

Why would a documentary that emphasizes Black resistance to slavery leave out John Brown, who armed enslaved people in a revolt for which he gave his life? I can only think because it would break the 1619 Project’s claim that Black people acted alone. The show, astoundingly, also passes over Lincoln’s famous “House Divided” speech in 1858. In fact, it claims that Easterners didn’t know much about Lincoln’s views—this is wrong. His 1860 Cooper Union address in New York—a brilliant, epic dismantling of the arguments for letting slavery expand—and his debates with Douglas were printed in their entirety across the North, making him a household name and a standard bearer for the antislavery cause. While William Seward was the first choice at the party’s convention in 1860, Lincoln was the second and won the nomination after several ballots.

The film keeps insisting that Lincoln, as president-elect, merely wanted to stop slavery’s expansion. Again, it makes no mention of the fact that he saw the halting of its spread as the way to start destroying it everywhere. It paints his first inaugural address as weak and conciliatory toward the South because he promised them not to interfere with their “property.” Once more, this was Lincoln merely underscoring that he accepted—as did almost everyone—the legal protections of slavery by the Constitution where it already existed. But he and the white South knew he was being coy—his ultimate goal, along with the Republicans in Congress, was in fact to put their civilization to an end. Legally, he couldn’t say that he would strike at slavery in the South by direct action—that would have been unconstitutional, and he had not been elected on that platform. But this was a clever dodge on his part to try to stop the South from seceding.

Once the Confederates fired on Sumter in April 1861 and made war on the United States, the whole ballgame changed. Here again, though, the documentary distorts the record. The series states that enslaved people knew about Lincoln and that he was on their side, though it doesn’t underscore the implications of this. Instead it tells the story of how three enslaved men in Virginia who ran away to Fort Monroe, controlled by Union forces. It does so to emphasize Black agency and the idea that the enslaved people took matters into their own hands and started freeing themselves.

I’ll have a lot more to say about this theory in another post, but let’s pause and examine what’s happening: these men fled their enslavers, a bold act of seizing freedom. But they did so because they knew that an anti-slavery government was finally in power in Washington, and that the war was being fought because Lincoln threatened slavery. In other words, the presence of a friendly Federal government under Lincoln—plus the protection that the Union Army offered them—is what helped the enslaved men to run. From the beginning, then, Lincoln’s antislavery policies were a catalyst for enslaved people to take bolder action. This is a case of how slavery was destroyed from both the top-down and the bottom-up at the same time.

But the series claims otherwise: it states that enslaved people were “way ahead” of the Republicans in Washington, perceiving that the war was about their freedom when Lincoln was still trying to fight a limited war without touching slavery. This is not the full picture. As Oakes relates in Freedom National, the Republicans from the beginning knew that if war came, then they would get much more power to strike at slavery. They knew of the long tradition of using the military to emancipate enslaved people so as to weaken your enemy. In fact, the British did this to the Americans during both the War of Independence and the War of 1812. The United States did the same during the Seminole War in Florida in the 1830s.

These instances weren’t about abolishing the laws creating slavery, but emancipation of individual men and women as an act of war. During the secession crisis in 1860-61, then, the Republicans warned the southern Congressmen on the floor of the House and Senate that if they seceded, war would follow. And with war would come the power by the Federal government to emancipate enslaved people directly through military means. If you do this, they told the South, we will start emancipating your slaves. The Confederacy knew this, but they gambled that they could win the war before Lincoln’s government could make good on this pledge.

So when the three enslaved men ran to Fort Monroe, the Republicans in Congress were waiting for them. They expected this, had prepared for it, and knew exactly what to do. Benjamin Butler, commanding the fort, asked for instructions. Congress immediately declared them emancipated by the laws of war. And they went further, passing the First Confiscation Act that summer in 1861, stating that any enslaved people who came into Union lines would be freed. Lincoln immediately signed this bill into law and instructed the War Department to carry it out. Here we have emancipation happening within weeks of Fort Sumter—Lincoln and Congress acting by force to undermine slavery directly. (Oakes summarizes all this in several articles for Jacobin, here and here.)

But instead of highlighting this haste, the documentary peddles the line that Lincoln stumbled to emancipation, wanting to end the war quickly and restore the Union. Cobb paints him as a Hamlet figure, slow to act, overthinking things, his heart not big enough to care about Black people. Kellie Carter Jackson makes the same claim over and over. When she states that Lincoln didn’t set out at the beginning of the war to emancipate the enslaved en masse, this is technically correct. But it misses the broader truth—it buries the lead. Lincoln set out in 1854 precisely to end slavery through legislation, however indirect. His change as the conflict progressed, then, was one of strategy, not goal. Yes, his immediate objective after Fort Sumter was to bring the conflict to a swift resolution. But that was with an eye toward resuming the legal plan to eradicate slavery. And as I’ve just pointed out, even at the war’s outset, he and the Republicans began to use their war powers to emancipate enslaved people in the South. The episode gives them no credit. This becomes a disturbing pattern.