This review was originally published in Critics at Large.

The Worst Person in the World

Socialists are quick to point out that we’ll still have problems after the revolution—they’ll just be more interesting. With our material conditions satisfied, we’ll have the time and means to engage more passions, pursue more adventures, and take more lovers. Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s latest film, The Worst Person in the World, gives us a tantalizing window into this world. Its vision is a society where young people can afford sleek, modernist flats, practice fulfilling avocations, and indulge the varieties of self-expression—all while holding jobs in the service sector. Who needs heaven when you can have social democracy?

With this picture, Trier brings his Oslo Trilogy to a poignant close. The series began in 2006 when he and co-writer Eskil Vogt released Reprise, a Joycean exploration of artistic ambitions between friends that introduced audiences to Anders Danielsen Lie. Lie’s become something like Trier’s muse; the actor’s appeared in each of the Oslo pictures—devastatingly so in the second, Oslo, August 31st (2011). There he portrays a heroin addict who journeys from rehab to fatal relapse in the course of a day. Along the way, Trier folded in elements of existentialism and phenomenology that created a haunting mood of angst. He deepened that philosophical exploration with Louder Than Bombs (2015), an American film that explored the death of a photojournalist through the fragmented consciousness of her kin.

Lie returns for The Worst Person in the World, this time in a supporting role: that of Aksel, a graphic artist living in the capital. He’s partnered to Julie (Renate Reinsve), a young woman whose search for self launches the film on its turbulent trajectory. Trier’s pictures have been compared to the French New Wave, and never has this felt more true than here. The movie begins in a spirit of exuberance, akin to Francois Truffaut’s opening gambit in Jules and Jim (1962), and you race to catch up to its frenetic rhythm.

It discovers Julie in medical school for a hot second until, grossed out by dissection, she realizes she wants to learn what’s inside the mind, not the body. But no sooner does she switch to psychology than she abandons that plan, too, to pursue photography. These shifts happen rapidly, merging in heady fashion with her altered hairstyles and romantic flings—first with a professor, then with one of her models—before she meets Aksel at a party. She moves in with him, and the pace of the film settles down.

The narrative unfolds in a series of twelve chapters, turning Julie’s tale into a Bildungsroman. As they progress, she explores the emotional terrain of her relationships and searches for her identity. In “The Others,” she and Aksel visit his family for a weekend, during which they see his niece throw a tantrum that prompts a frank discussion about having kids. Julie, younger than him by over a decade, harbors doubts, while he insists she’d make a great mom. Already, the film plants a seed of doubt as to whether the couple can navigate their difference in life stages. It sprouts in the next chapter, “Cheating,” in which she sneaks off and crashes a wedding reception for thrills. She finds what she’s looking for when she comes on to a hunky guest, Eivind (Herbert Nordrum) and he responds in kind.

After some initial flirtation, they confess to each other that they’re each in a relationship and monogamous. That only excites them the more, however, as they decide to push the limits of their fidelity. They spend the night engaging in intimate, bizarre behaviors—nocturnal reveries that climax in a potent image in which she inhales cigarette smoke from his mouth after he takes a drag. She thinks that’s the last of him, but fate intervenes—while working her job at a bookstore some weeks later, she sees him enter with his partner, Sunniva (Maria Grazia Di Meo). Dumbfounded, he surreptitiously imparts to her that he works at a local cafe.

Julie’s connection with Eivind creates the central conflict, as it forces her to confront her dissatisfaction with Aksel. Her boredom dovetails with unresolved feelings about her father, an estranged figure who neglects to attend her thirtieth birthday party over bogus claims of a bad back. When she and Aksel interrogate him about this, he makes up more excuses for why he won’t visit them in Oslo. Later, Julie sits in silence as Aksel holds forth over dinner with friends about how badly his comic book character, Bobcat, was adapted for the screen. Aksel’s style is punk-underground, but the filmmakers have turned the profane, edgy animal into a family-friendly Christmas character. The chasm between him and Julie grows in her mind and she entertains thoughts of leaving.

These take on a magical quality when she and Aksel argue one day. Suddenly, we enter her consciousness and the world literally stops—Aksel’s suspended mid-sentence and she runs giddily into the streets, reality frozen in a luminous tableaux. Her fantasy takes on the style of the romantic musical, as she finds Eivind at his job and absconds with him. Through the streets they frolic, the cityscape luminescent and vibrant with life. The director imbues this sequence with the aesthetics of films like Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964).

But this is Scandinavia, not Hollywood, and Trier and Vogt are more sophisticated filmmakers than to leave us with a conventional ending. In fact, you never quite know where the movie’s headed, even as its surprises feel true. This alchemy gives the picture an open, authentic quality. It inhabits Julie’s twenty-something point of view, that time where life’s options seem limitless, its stimulants intoxicating, and your desires pull in multiple directions. She’s not sure what she wants, and her unpredictability arrests you.

But she’s also blinded, as we all are, by what she doesn’t have. The movie depicts the temptation to denigrate our partners, romanticize others, and idealize relationships of the past. We never get a full picture of Aksel and Eivind, as we see them only through Julie’s moods. At first, she feels that Aksel patronizes her with his counsel, while Eivind offers more excitement in bed. Yet later, she realizes that behind his penchant for pedantry, Aksel provided an intellectual life that she finds lacking in the toned barista.

The movie allows Julie to make a mess of things without passing judgment. In fact, Trier never looks down on any of his characters, even when his protagonist does. At one point, Julie authors a blog post about feminism and oral sex that she shows to Aksel. He’s impressed and encourages her to write more. But when Eivind reads it later, he assumes it’s a piece of autobiography, a reaction that infuriates her. As with Aksel, she paints his behavior in an uncharitable light—the guy’s trying his best to do right by her. She’s cruel to both men at times. The film doesn’t punish her for her errors of perception.

It’s a coming-of-age tale, though, and she loses things that she can’t get back. When you’re young, you think you’ve got endless shots at romance. Julie gets a reality check—true connections are rare. And yet they never leave you. At one point, she does magic mushrooms with Eivind and his friends. Trier films this as a surreal episode in which her body transforms into that of an old woman, breastfeeding an infant while her former partners watch. You see her unconsciousness working through her complicated feelings about maternity and mortality.

As the main character, Reinsve incarnates the young woman’s many shades of personality. Her Julie is smart and curious, and she embodies the outlook of an emergent generation the way Greta Gerwig does in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (2012). Yet in some respects, Julie’s part is underwritten. You get why she’s interested in Aksel and Eivind—the former for his avant-garde art, the latter for his masculinity. But it’s somewhat harder to know why they stay with her. She’s sexy and a turn-on at parties, but Trier and Vogt don’t let you see her other layers. You start to wonder what’s become of her photography career, and you wish the screenwriters would lend her some dialogue out of Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise trilogy.

Anders Danielsen Lie has an impassive face that frightens you in Oslo, August 31st, and even more in Paul Greengrass’s 2018 film, 22 July (where he played the terrorist Anders Breivik). Here he takes a contemplative turn, and his Aksel is just as memorable. When he and Julie reunite, their scenes reveal depths of reflection that neither you nor the woman are prepared for. Nordrum holds his own as Eidvin, and he shares a comic sequence with Di Meo and a caribou that sends up Nordic environmentalism.

Norway’s the most surprising country. Of all the nations of Europe, it was out of its backwater fjords that modern drama was born. Trier may not share quite the same sensibility of Ibsen, but over a hundred years later, he’s taken a spot as one of the leading directors of the Continent. Like his peer, the author Karl Ove Knausgård, he makes his art out of the quotidian details of life, but builds even further with his command of style and expression. The Worst Person in the World—a title as enigmatic as its protagonist—shifts moods and technique effortlessly. It even features an iris shot, a silent-film edit you never see today. The pictures of the French New Wave finish abruptly, as if the energy fueling them burns out in a flash. Trier and Vogt craft a more rounded, complete arc for Julie, leaving her with renewed possibilities, laced now with irony and wisdom. Long after the lights come up, you’ll wonder where she’s gone, and wish you could tag along.

Cyrano

Speaking of passion, there are few works as poetic as Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac. Though written in 1897, almost twenty years after naturalism hit the stage, the Frenchman’s play is emblematic of the Romanticism that vied for audiences in the late-19th century. Set to rhyming couplets, it immortalizes the brash, verbose, swashbuckling bard with the most iconic nose in Western literature. Cyrano, a cadet in the French army of 1640 Paris, stems from the chivalric lineage of Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. Unfortunately, his colossal appendage renders him repulsive in his eyes and scuttles hope of consummating his love for Roxane, his beautiful cousin.

To compensate, he engages in wordplay and swordplay that delights the audiences of both his day and ours. And more: when he discovers that a dashing, dimwitted new recruit, Christian de Neuvillette, also pines for the maiden, he decides to become the dullard’s ghostwriter. He lends his poetic voice to the man, first via epistles, then literally when Christian woos Roxane beneath her balcony. At the same time, he helps the couple evade the machinations of the Count de Guiche, who seeks to make Roxane his own. The Count’s scheme fails—Christian and Roxane wed in secret—but he avenges himself by sending the cadets to the front.

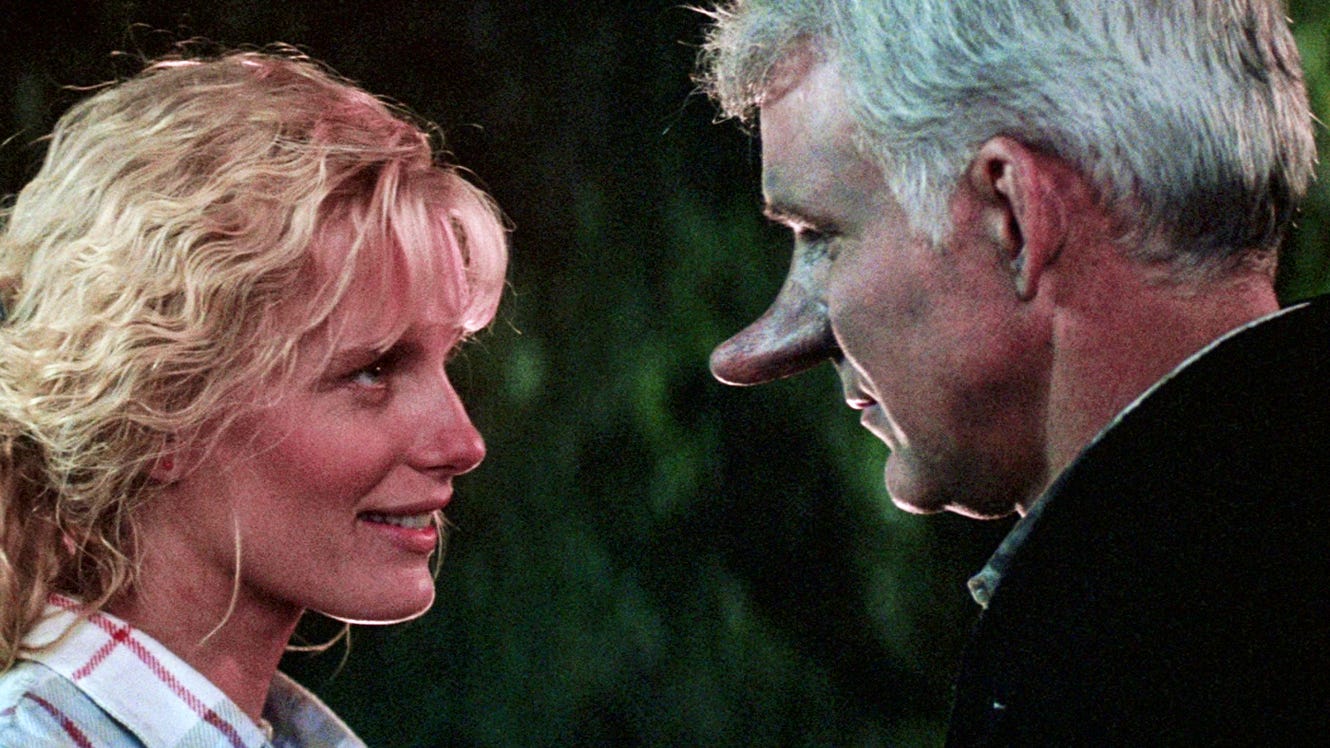

The play’s been adapted many times, most sweetly by the gifted Australian Fred Schepisi with his 1987 film, Roxanne. Steve Martin, who wrote the screenplay, stars as Charlie “C.D.” Bales: Cyrano reconceived as an acrobatic fire chief in a Pacific Northwest town. The Brit Joe Wright—who helms the new picture Cyrano—would be just my pick to direct this thrilling entertainment today. He’s displayed an audacious capacity for rendering literature to film, first with Pride and Prejudice (2005), then followed by Atonement (2007). He also made the 2021 thriller The Woman in the Window (with Amy Adams); the humanistic, inspirational film The Soloist (2009), about an L.A. journalist (Robert Downey, Jr.) who befriends a man living on the streets (Jamie Foxx); and returned to the Second World War with Darkest Hour (2017)—a galvanic picture about Churchill during the Blitz that features a tour-de-force from Gary Oldman.

His Anna Karenina (2012) was a conceptual flop, despite complex performances from Kiera Knightly and Jude Law. But it failed on such a sophisticated level that you couldn’t help but admire it. He set portions of Tolstoy’s realist novel in a theater, the characters playing out scenes on a stage even as the narrative spilled out beyond it. The theatricalism worked against him in that picture, but it serves him well in his latest. Cyrano opens with a cinematic coup that matches the bravado of Rostand’s first act. Wright’s direction of this sequence is a sumptuous, textured, ravishing feast for the senses. The imagery he and his veteran cinematographer, Seamus McGarvey, conjure of Parisians as they flock to the theater channels Jean Renoir in its use of deep focus and crowds.

Wright works from a script by Erica Schmidt, based on her 2018 musical for the stage. Her key concept is to alter the title character’s famous physicality: Cyrano’s played by Peter Dinklage, making the soldier’s obstacle an issue of his height, not his nose. Somehow this decision works, mostly because Dinklage gives such a winning performance. Though small in stature, his spirit fills the role. Which is exactly why Schmidt’s other ideas exasperate you. Rostand lent his hero some of the most ornate lines in literature, and you pay to hear them brought to life. Dinklage has the chops, but Schmidt, inexplicably, cuts most of them. The balcony scene rivals Romeo and Juliet in literary consciousness, yet the filmmakers reduce Cyrano’s monologue to a remnant. The entire conceit of Cyrano de Bergerac is that Roxane falls in love with his poetic mind, not Christian’s gorgeous face—but how can that idea come across if we don’t hear the title character bare his soul?

Martin and Schepisi squared this circle by retaining the play’s signature moments but updating them for romantic comedy. In the scene where Cyrano humiliates an aggressor by weaving a tapestry of self-deprecating insults, Martin plays the exchange like a stand-up in a bar. For the balcony wooing, he makes Chris (played as a delightful dunce by Rick Rossovich) wear a wire so he can feed him lines to Roxanne (Daryl Hannah). Martin’s philosophic wit channels the spirit of Rostand for a modern audience and a contemporary vernacular.

In the new picture, Schmidt and Wright replace the verse with tunes conceived by Bryce and Aaron Dessner. This starts out well enough with Roxane’s song, “Someone To Say,” an evocative opener that melds with the theater scene. But soon things go off the rails: the Dessners render Cyrano’s duel onstage in the rap mode of Hamilton, which doesn’t fit the overall style and isn’t maintained by later numbers. In fact, the music quickly takes on the banal, bathetic quality of Les Miserables. If you’re going to excise Rostand’s lines, at least write lyrics worthy of his art. The Dessners don’t, and it kills the pleasure.

Likewise with the decision to compress the material as much as possible. The play is an elaborate, sprawling epic with each act a massive undertaking. It could be a great musical in the right hands, what with its huge set pieces and supernumeraries. But Wright and company shrink boisterous scenes like the Poet’s Cookshop to an afterthought (this is especially disappointing because they cast the great, tragicomic Peter Wight as the head baker, Ragueneau). The film’s visuals captivate the eye, yet the choreography leaves you wanting. In the case of Roxane’s “I Need More,” it takes on the aesthetics of softcore erotica—not the desired effect.

At least that number leaves an impression, however unpleasant; the rest blend together blandly. Things get more bizarre at the front, when the Dessners give a ballad to the cadets, “Wherever I Fall,” just before their doomed charge. It’s not only that the timing distracts from the dramatic climax—Cyrano’s attempt to save Christian. It’s that you don’t know who any of these singing soldiers is. And when you do recognize one—the Irish musician Glen Hansard—you find yourself wondering how the hell he got here (both in the movie and the scene).

Watching this picture, you wish Wright had adapted Rostand’s play right to film and bypassed Schmidt entirely. The sly Australian actor Ben Mendelsohn gets under your skin as de Guiche, what with his lascivious lisp and flamboyant affect. And Bashir Salahuddin lends a welcomed larger-than-life quality to Le Bret, Cyrano’s comrade in arms. Haley Bennet is a striking, red-headed Roxane, but her songs cheapen her beauty, which Rostand intends as a symbol of purity. Kelvin Harrison Jr. has the features to play the handsome Christian and even renders the man interesting. You want more interchanges with him and Dinklage. The latter makes for a soulful Cyrano, recalling his touching performance in Tom McCarthy’s small film The Station Agent (2003).

When Cyrano expires at the end of the story, having finally revealed the truth to Roxane, you have the elegiac sense of a great spirit leaving the world. Dinklage gives you a taste of that feeling, but it’s more a response to the actor himself than his character. Without those grand speeches, Cyrano seems a mere mortal. If Wright and Schmidt felt that audiences can’t handle Romantic poetry, they’re mistaken. I recall a college production where we performed the play in all its five-act glory. Despite four intermissions, the crowd came back each time. You don’t need to dumb down the classics. With war returned to Europe, we need them more than ever.

Bonus Content

Joachim Trier interviewed on The Late Late Show with James Cordon:

Peter Dinklage interviewed on The New Yorker Radio Hour:

I can't wait to see both. Love the new logo. Why a feather? Love it when you include music or film clips. I agree on the language I think there are many folks who hunger for language that describes emotion. No emojis or abbreviations but a genuine attempt to share what one is feeling with another.