I.

I visited Philadelphia last weekend to see my best friend, and during the trip he showed me the new statue at City Hall of a prominent historical figure: Octavius Valentine Catto. Mr. Catto played a major role in Pennsylvania during the Civil War and Reconstruction, raising troops for the United States Army, advocating for the desegregation of public places, and fighting for the right to vote. On Election Day in 1871, he was murdered in the street by racist aggressors (many Irish). Now, I’ve read countless books about that era, yet I’m ashamed to say that I’d never heard of him. My guess is most white Americans haven’t, either. This makes him yet another largely unsung Black political hero.

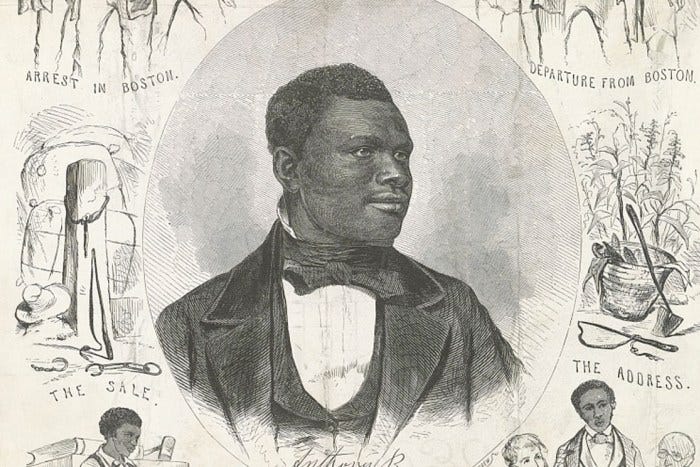

Starting a few years ago and continuing through the pandemic, I’ve devoted my free time to writing a screenplay about two others: Anthony Burns and William Cooper Nell. The story of Anthony Burns constitutes one of the most dramatic historical events in American history—certainly in the history of Boston. With Black History Month upon us, we’d do well to familiarize ourselves with it. Burns was born into slavery in Virginia in 1834 in Stafford County. His youth mirrors that of Frederick Douglass in many respects. Like Douglass, he was hired out by his enslaver and learned to read and write in the course of his labors. He was shaped by the Bible and became a preacher on the side. In 1854, he followed Douglass’s footsteps and seized his freedom by escaping—in his case, on a ship to Boston.

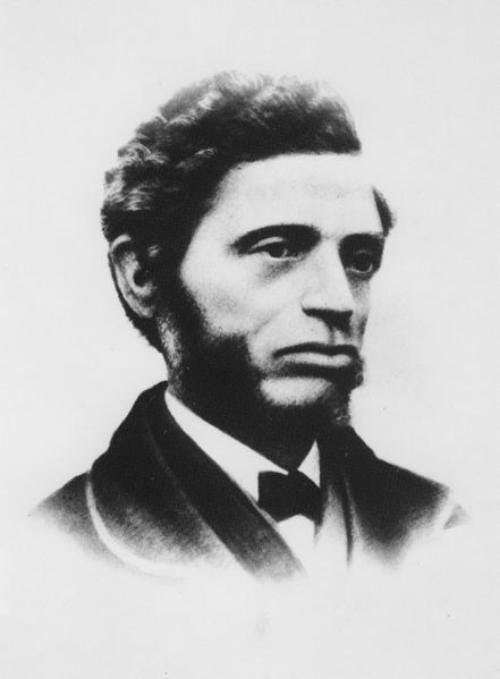

Many white Bostonians don’t know that the city had a thriving free Black community during the antebellum period (at least I didn’t). The neighborhood of the West End (where Mass General Hospital stands today) hosted numerous Black businesses, churches, and social organizations. Its residents included the artist Edward Bannister, his wife and hair salon owner Christiana Carteaux, and clothing merchant and Underground Railroad conductor Lewis Hayden. The center of the community was Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury, led by Rev. Leonard Grimes. All of them were leaders in the antislavery movement, working together with white activists like William Lloyd Garrison and Theodore Parker, the fiery Unitarian minister. Perhaps no Black leader was more influential than William Cooper Nell. Born in Boston in 1816, Nell joined the cause of abolition at a young age. He became Garrison’s protege, often representing him at events, and contributed journalistic essays to The Liberator and Douglass’s The North Star.

Not content with attacking slavery, he also set his sights on the racism of his home city. He led a long, fraught campaign in the 1840s to desegregate the Boston railroad, as well as the public school system. In 1853—almost a hundred years before Rosa Parks—he and two Black women (Sarah Remond and Caroline Putnam) were forcibly ejected from the Howard Athenaeum while trying to sit in the seats they’d purchased. They sued and won a symbolic victory in the courts. Nell also wrote two volumes on Black heroes of the American Revolution, the first historical studies of African Americans ever published. He advocated tirelessly for the city to erect a statue of Crispus Attucks, something it didn’t get around to until 1887, thirteen years after Nell’s death.

Nell sat on the State Council of Colored People of Massachusetts, a precursor of the NAACP, as well as the Boston Vigilance Committee. The latter was formed in response to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which increased the power of the Federal government to hunt down Black people fleeing bondage and return them to their enslavers. The Committee was biracial, boasting influential white and Black members, and provided aid and assistance to fugitives looking to settle in Boston or move north to Canada. Against contemporary imaginings of abolitionists as whiggish white men smoking in parlors—and contrary to the claims of the 1619 Project of The New York Times—the antislavery movement was an integrated endeavor. Black people did not struggle alone. The activists were young, dynamic, and diverse. Women formed the backbone of the operation, doing the grunt work while men served in leadership (a sad, familiar tale). While Brahmins formed the intellectual vanguard, working-class whites were its foot soldiers.

Massachusetts was the epicenter of the nascent industrial revolution, and the workers in the Dickensian factories of Lowell, Lawrence, and Leominster connected their harsh conditions with the plight of enslaved Blacks. Today almost all of us work for wages; we view this as a natural state of affairs. The people of the early 19th century saw it as anything but. Freedom, for them, meant economic independence, not just political. The ideal of the free labor ideology was of a yeoman farmer or modest artisan, both working for themselves—not an employer. You might do service for someone else for a few years, they thought, but soon you’d move on and open your own business. The notion of whoring yourself out to a boss your entire life struck them as outrageous. And the idea of doing so for a large corporation was positively anathema.

Despite these beliefs, leaders of the free labor ideology imagined a natural harmony between labor and capital. They were uneasy with organized actions like strikes. But others, especially workers, saw the writing on the wall: capital was becoming king. The working class of the North labeled their status “wage slavery,” making their condition a twin of chattel slavery. The antislavery crusade was thus a dual project to dismantle the plantation system of the South and the factory network of the North—the Lords of the Lash and the Lords of the Loom. Both were forms of unfreedom, incompatible with democracy. Destroying chattel slavery had to come first, being the greater evil. But the movement, they believed, would continue on and abolish capitalism as well. The racial struggle was yoked to the class struggle, something many of today’s liberals don’t get.

II.

Enter Anthony Burns. After a harrowing passage, he stole into Boston in February 1854. Through the help of the antislavery community, he found employment in a local shop and settled down. For several months, things went well. But for reasons that aren’t clear, he mailed a letter to his brother back in Virginia telling him of his new home. The post was intercepted and shared with Charles Suttle, Anthony’s enslaver. Operating under the Fugitive Slave Act, Suttle journeyed to Boston in May and secured permission to have Burns arrested. Anthony was taken into custody while working at the clothing shop and imprisoned in the courthouse.

Word spread like wildfire. Nell, Parker, and the other members of the Vigilance Committee sprung into action. They knew what to do. Just three years earlier, the same thing had happened to an escaped Black man named Shadrach Minkins. The Fugitive law specified that the accused be given a special hearing to determine his identity. Such legal proceedings were a sham, and everyone knew it. The accused had no rights under the law, including for representation, and couldn’t even speak in his own defense. Minkins was hauled before a judge, but before the trial could conclude, a group led by Hayden burst in and physically liberated him from the U.S. Marshalls. They shuttled him into hiding and, eventually, to Canada.

With the Minkins rescue in mind, the Vigilance Committee called for a mass meeting at Faneuil Hall. Over 5,000 people attended, and Parker delivered a blistering call to arms:

The Slave Power is on the move! They have taken Texas and Mexico, the President and Congress. Now they seek Kansas and Nebraska and Boston! When the Slave Power has annexed Cuba, when they've allied with Brazil and its millions in bondage, when they've re-opened the foreign slave trade–with all the appalling horrors of the Middle Passage, and the Atlantic is again filled with the bodies of dead Africans–then we may think it time to waken to our duty. But it will be too late!

Driving like a freight-train, the crowd in bedlam, he reached his soaring climax:

Friends, I am a clergyman. A man of peace. I love peace. But there is a means, and there is an end. The Law of Liberty is the end, and sometimes peace is not the means. I am not a young man. I have heard hurrahs and cheers for liberty many times; but I have seen few deeds done for it. So I ask you, tonight, are we to have deeds as well as words?! Who will stand for Liberty?!

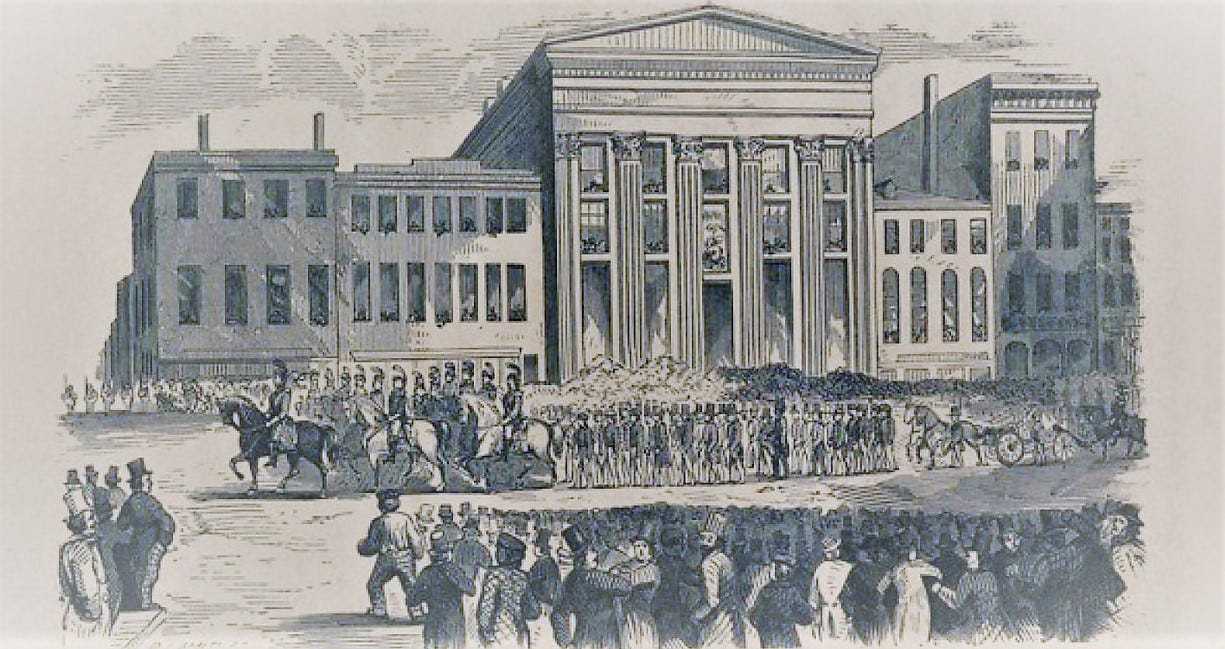

At this, someone shouted that a mob of Black people was racing toward the courthouse square. Whether it was part of the plan or a spontaneous riot, we’ll never know. What we do know is that, led by Nell and Hayden, a horde of over 500 laid siege to the building housing Burns. Think the demonstrations of 2020 were bold? Think again. For hours, these fearless souls battled the police guarding the jail. They threw stones, battered doors, and swung sabers. They punched and kicked and knifed and shot. People died. But they could not get to Burns.

In response to this unrest, President Pierce ordered in the military and declared martial law. Despite the work of every historian since the 1960s, a pluarlity of Americans cling to the fiction that the South only wanted to protect states’ rights, being conservative guardians of sacrosanct Federalism. This is a lie. The southern oligarchs used every means at their disposal to grow slavery, including the national government (which they dominated for decades). The Fugitive Slave Act expanded Federal power over local authorities. Armed with this new mandate, Pierce sent in the guns. Thousands of soldiers took up posts at government buildings and in the streets. Burns’s hearing was hastily moved up.

But the abolitionists were one step ahead of them. They put out notice of the impending trial and called on all people to rally in Boston. Horrified by the sight of a free man kidnapped in broad daylight, outraged by the military’s desecration of their streets, the masses poured into the city. Tens of thousands streamed in from the surrounding towns. Worcester, with its large working class, sent in hundreds. It’s hard to know how many rallied, but historians estimate over 50,000 people flooded the streets around the courthouse.

Burns was defended by Richard Henry Dana, Jr., the white attorney who represented many fugitives, working pro bono. But the deck was stacked against him and the outcome predetermined. His client was remanded back to slavery. Suttle was in attendance; as a way of exacting payback, the Vigilance Committee had ordered Suttle himself arrested for kidnapping, making him spend a night in jail. But the enslaver made bail and was released. He now waited to reclaim his human property.

What happened next was like a scene out of a Spielberg movie (phone’s waiting, Steven). A phalanx of Marines encircled Burns, who was marched down the courthouse steps into a formation of troops. Cannons were aimed at the massive crowd. At the sight of Burns being taken away, the masses erupted in rage. Banners were hung and signs hoisted. Buildings were draped in black crepe and a giant coffin with the word Liberty paraded up and down like a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day balloon. Distraught onlookers climbed onto rooftops and gazed out of windows.

Burns displayed poise and calm as he walked the streets. People grappled with the soldiers; makeshift bombs were thrown; Black men were arrested in their attempt to get to Burns. Cavalry charged citizens trying to rush the detachment. As the procession reached the docks, it was met by a new crowd, many of them sailors and harborworkers. Channeling the spirit of Attucks, these workers pitched into the soldiers, who fired over their heads and clubbed them with their rifles. Amidst the fray, Burns was marched onto a ship and thrown into the hold. The abolitionists had failed. Anthony was sent back to slavery.

III.

The Burns event electrified the North. Up until that point, the antislavery movement had been seen as too radical for moderates. Now, they recoiled at the use of national power—the military no less—to hunt down and return one man to slavery. They realized that the white South was determined to defend slavery at all costs, and that the conflict between the two sections was reaching that of war. People had been shot down in the streets of Boston—Boston. The affair coincided with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in Congress, which shred the Missouri Compromise and opened the West to more slave states. For many, this had the effect of a conversion. On the 4th of July, two months after Burns’s arrest, Garrison burned the Fugitive Slave Act before a rabid crowd. When he was done, he burned the Constitution too.

One person aroused by these events was a prairie lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. Galvanized by the Nebraska Act and the Burns debacle, Lincoln took center stage after several years of inactivity. He threw himself into antislavery politics, helping form the Republican Party with its plan to strangle slavery by abolishing it in the West, removing its support in the Federal government (including for the Fugitive Act), and setting it on what he called the road to ultimate extinction. When he was elected President in 1860 on a platform of choking off and killing slavery, the white South rose in rebellion. The Civil War was brought on by a thousand different events. But Anthony Burns was a pivotal one.

Nell went on to render noble service during the war, fighting for Black men to serve the United States as soldiers and sailors. In 1861, he was hired as a postal clerk, making him the first African American to hold a Federal civilian post. He died in 1874. And Burns? The story has a mixed, but inspiring, ending. He suffered terrible maltreatment on his return to Virginia, and was sold to a plantation in North Carolina. Hope seemed lost. But through a series of improbable turns, word reached back North of his whereabouts. Rev. Grimes took up a collection and successfully purchased Burns’s freedom from his new enslaver. Anthony returned North in triumph, speaking before large crowds in Boston and New York and attaining the celebrity status of fugitives like Henry “Box” Brown. He eschewed the limelight, however, wanting to serve God as a minister.

Eventually, he enrolled in Oberlin College in Ohio and followed up with seminary studies in Cincinnati. Upon ordination, he preached in Indianapolis before accepting a call to the Black Baptist church in St. Catherines, Ontario. But the abuse he’d received during his enslavement took a toll, his lungs blasted from the prison cells he’d been confined to. On July 17, 1862, as the war raged on sea and soil, he died at 28—just four days after Lincoln announced to his stunned Cabinet that he was going to issue an Emancipation Proclamation. Three years and a million dead later, Burns and the abolitionists were vindicated: slavery lay in ruins. As for capitalism, well, that battle continues. In my screenplay, I give Burns a scene in which he displays his rhetorical power before the congregation. I’ll let him have the final word:

To my former Christian brethren in Virginia, I give a verse to ruminate upon. So hard. So impenetrable. Study it carefully. "Do to others as you would have them do to you." Here, now, I have found refuge. But in Egypt my people still toil under Pharaoh's yoke. Let us join the Lord. Let us throw down Pharaoh and all his chariots and charioteers! Let us cast them into the sea of God's justice forever!

Additional Resources

The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War by Andrew Delbanco

Anthony Burns: The Defeat and Triumph of a Fugitive Slave by Virginia Hamilton

The Trials of Anthony Burns: Freedom and Slavery in Emerson’s Boston by Albert von Frank

Fugitive Slave on Trial: The Anthony Burns Case and Abolitionist Outrage by Earl Maltz