If you want to have your joy for motion pictures restored, look no further than The Last Movie Stars, Ethan Hawke’s six-part documentary about Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman. Hawke pulls off something that Hollywood seems incapable of these days: he celebrates, without apology, the central space that movies and their makers occupy in American consciousness. In a social scene replete with celebrity romances, Woodward and Newman produced one of the most mature, fruitful, and culturally significant. Hawke tells the story of their careers and marriage through their words, and—most gloriously—their performances. In so doing, he gets at the mass intimacy between actors and audience—how we identify with screen giants we both do and do not know. While the film stumbles in places, it’s a shot in the arm.

The series begins with zest, opening with the story of how Hawke and his father played hooky from church one Sunday to see Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). “Since that day,” he says, “movies have been the church of my choice.” He then appears in a montage of Zoom conversations with fellow actors, who represent some of the most recognizable of our time—Laura Linney, Mark Ruffalo, George Clooney among them. Hawke explains how Woodward and Newman’s children approached him during COVID and asked if he’d helm a film about their folks. As if that wasn’t enticing enough, they gave him a trove of interviews Paul conducted late in life. He’d hoped to pen a memoir, and sat down with dozens of people from over his long career. In a Lear-like fit, he took the tapes out back one day and put them to the torch (“Kind of awesome when you think about it,” Sam Rockwell says). The transcripts survived, however, and Hawke got the inspired idea to cast his friends as legends of the past.

As Gore Vidal (read brilliantly by Brooks Ashmanskas) says at the outset, Paul and Joanne—whom he counted as friends—represented the last of a dying breed: actors who achieved both artistry and royalty. They were part of a cadre of wunderkinds who popularized Method acting in the ‘50s, including Montgomery Clift, James Dean, and Julie Harris. Assembled by Konstantin Stanislavski for his Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) at the turn of the 20th century, this “system” codified the trend toward verisimilitude that Western theater had been undergoing since the 1740s. More a style than a technique, it aims to reproduce recognizable reality on stage and screen—a creative mood that (drawing from Tolstoyan spirituality) he named ‘perezhivanie’ (‘experiencing’ or ‘living the part’).

The Method (as it came to be known in the U.S.) prescribes several tactics to help the actor achieve this state of “realism” or “naturalism” (technically not the same, but used interchangeably). First, imagine yourself into the character’s given circumstances through radical empathy (“The Magic If”). Secondly, justify all behavior by breaking down scenes into playable actions in line with your character’s “super task.” Thirdly, concentrate on objects of attention to achieve mindfulness of the present moment (or “public solitude”). Fourthly, practice intimate communication with the other actors in the scene (an elite ensemble is the ideal). Finally, mine your personality for truth and draw on different sides of yourself to explore characters.

By the time Woodward and Newman arrived, the Method had been part of American theater for thirty years, beginning with the MAT’s visit to New York in 1922. Richard Boleslavsky, one of its members, further popularized it with a famous lecture series, which led to the founding of the Group Theatre in 1931. While it lasted just a decade, the Group’s impact on American film and theater was incalculable. Only a single performer in the company—John Garfield—became a movie star. But it produced, in Clifford Odets, one of the country’s three greatest playwrights (the others being Eugene O’Neill and Tennessee Williams) as well as a number of acting gurus—chief among them Stella Adler, Lee Strasberg, and Sanford Meisner.

Friends turned rivals, these giants passed on the Method to numerous disciples through their workshops and seminars. Newman and Woodward were among them, honing their skills at the Actor’s Studio with Strasberg while peers studied under Adler across town. Through this class of gifted youths, many of whom became stars, Stanislavski’s system fused with the postwar American zeitgeist: a gritty existentialism born of the atomic age; the rediscovery of Freudian psychoanalysis; and the emergence of teenagers as a cultural phenomenon. Hawke’s first episode captures the heady days of the New York scene, recounting how Paul and Joanne met backstage during the 1953 premiere of Picnic by William Inge. They commenced a torrid affair; it lasted five years, until he at last left his wife, Jackie, to marry Woodward.

Joanne rocketed to success, playing over a hundred episodes of television in two years before she broke into film. She won the Oscar for Best Actress for just her third, 1957’s The Three Faces of Eve, in which she portrays a woman suffering multiple-personality disorder. With hardly a plot, the picture proceeds like a case study as it dramatizes Eve’s diagnosis. The subject matter fit the times, though, as coaches like Strasberg were stressing neurosis as the source of theatrical truth. But for all this emphasis on pathology, Woodward’s acting is notable for how she locates the character’s personas through posture and movement. She marries this outside-in approach with a preternatural capacity to produce emotion on cue.

Clips of other films better showcase her talents, like a drunk bit from No Down Payment of the same year; her screen test with Dean for East of Eden (1955); and her sultry scenes with Marlon Brando in Sidney Lumet’s The Fugitive Kind (1960)—a Southern gothic reimagining of the Orpheus legend, written by Williams. With her razor sharp smarts and quicksilver quality, you can see why Paul became obsessed. For her, “everything’s instinctive, everything’s natural,” Vidal says, observing how women at that time were meant to be actresses in real life, as well as on the screen. Or as she put it:

Acting is like sex. You should do it, not talk about it.

She and Paul were having a lot of sex, but despite this, he couldn’t act. “The difference between her and Paul as actors,” Vidal continues, “is that he’s constantly thinking, thinking, thinking. It sometimes gets in his way.” Newman was all too conscious of his hang up, struggling in the shadow of Dean and, most of all, Brando. Less than a year his senior, from a similar midwestern town (Omaha vs. Newman’s Shaker Heights, OH) Brando leaped ahead of the pack with The Men (1950), A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), and On the Waterfront (1954). Karl Malden (Vincent D’Onofrio) calls him the hare, Newman the tortoise. Paul felt too normal by comparison, even though he’d lived more interesting experiences (he served in the Navy during the war; Brando was IV-F). Newman told it straight:

I don’t have the immediacy of personality. I’m not a true eccentric. I’ve got both feet firmly planted in Shaker Heights.

The Method’s been identified with abnormality by many because of actors like Dean and Geraldine Page. But it’s just as evident in placid performances of the era from people like Eva Marie Saint, Kim Hunter, and Rod Steiger. Newman’s real problem was that, whether playing imbalanced roles or not, he wasn’t comfortable in his own skin. “Those people, they’re authentically themselves,” he admits. “They’re not working to become something they aren’t.” He was, though, laboring into a lather with roles like Rocky Graziano from Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956). It looked mannered, and colleagues noticed. He remembers someone telling him the brutal truth:

“Ben Gazara thinks you’re a Shaker Heights asshole. It’s all manufactured. There isn’t a genuine moment.” And I knew that if Ben Gazara said that—if he said it was fake—it was fake.

When he played opposite Page on Broadway in Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth (1959), he literally ginned up tears by staring at a light in the mezzanine. Elia Kazan, who helmed the production, notes Newman’s repression. There was a sense of shame in his acting, the director says, a middle-class rectitude that he chafed against but couldn’t escape. Paul conceded as much:

You know what you signed for? An emotional Republican.

Hawke builds in so many layers this first episode it’s dizzying. Art as self-discovery is the theme. The film gets at how actors find themselves through characters, and the way we, in turn, find ourselves through them. It fails to sustain the energy, however, and loses its throughline. Similar to its subjects, the film gets bogged down in the mid-’70s. The couple’s trajectory crisscrossed after they wed; his fortunes soared once Dean’s death paved his way for films like The Hustler (1961), Hud (1963), and Cool Hand Luke (1967). By 1970, he was the biggest draw in Hollywood. Meanwhile, Joanne languished at home, career stalled, raising both their own kids and three from his first marriage.

When she returned to acting, it was often in poor material. She overcame it in 1963’s The Stripper (based on an Inge play), giving a buoyant, coquettish performance as a washed up beauty queen. But in Rachel, Rachel (1968) and 1972’s The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (both directed erratically by her husband) her emotional purity was turned into a fetish. Despite its vulgar association with the Method, Stanislavski denounced such a sin as the antithesis of his system. (Hawke perpetuates this fallacy, letting D’Onofrio indulge in a cringe-worthy display of “affective memory,” the most controversial, abused, and misunderstood of the Russian’s ideas.)

At this point, the documentary abandons acting to focus on the family’s domestic life. It underscores the trauma Paul and Jackie’s divorce visited on their kids, especially Scott, the eldest. It also divulges the extent of Newman’s drinking, which got so bad Joanne evicted him for a time. The kids attest to the couple’s explosive fights and his detachment from the family, made worse by workaholism and womanizing. The public image of the Newman-Woodward alliance was of a faithful marriage amidst a sea of hedonism. But the film reveals how Paul was having an affair at the same time that—dubiously comparing Joanne to a steak—he proclaimed his fidelity in an interview with Playboy. Driven by unnamed demons, he ground out his aggression through extreme habits like stock car racing and sky-dives. “Actors make for bad parents,” Joanne says.

Though he’d reached the pinnacle of box office success, in truth Newman still wasn’t an actor. In another interview from the time, he confessed the fact to Leonard Probst:

I’m falling back on successful things that you can get away with. I duplicate things now. I don’t work as compactly as I used to work, simply because the demands aren’t asked of me anymore.

This frank admission was all the more astonishing given that he’d just logged two of his greatest hits, Butch Cassidy (1969) and The Sting (1973). His impossible good looks (my mother had a pillowcase in college imprinted with his face, blue eyes ablaze) had become only more arresting, the androgynous sheen of the ‘50s giving way to coarse, rugged handsomeness. But Hawke acknowledges that, in this period, the pleasure of his performances came more from the overall style of the films than from his easy cool. Too often—including in the dopey, overrated Cassidy—he skated by on sex appeal and charm.

The documentary rightly credits Slapshot (1977) as, improbably, the movie where he broke new ground. A raunch fest about a minor league hockey team, the film gave him a chance to show off his gift for comedy—channeling a superannuated adolescence, his crass, unreconstructed Reggie Dunlap is irrepressible and irresistible. Around the same time, he made several Robert Altman pictures (Buffalo Bill and the Indians from 1976 and 1979’s Quintet) where he pushed himself into unconventional terrain. Hawke’s chief contribution is how he reveals the personal tragedy at the heart of this transformation: Scott’s death of an overdose in 1978. In a somber sequence, the director shapes images from Quintet (a bizarre, sci-fi dystopia) in which Newman places a corpse in a river while the narration tells of his son’s demise.

The pain and guilt that afflicted Newman changed him. What emerged in the ‘80s was the very quality that eluded him before: authenticity. Beginning in his mid-fifties, he turned in a string of credits that established himself as the emblem of middle-brow masculinity—a Henry Fonda everyman, whose husky voice and fine-tuned reactions seemed to flow from a wellspring of integrity. Predictably, Hawke names The Verdict (1982) and Martin Scorcese’s The Color of Money (1986) as the actor’s greatest roles. He’s very good in them, to be sure, even excellent, shaping his dialogue with precision. But his most profound performances come from two 1981 films the documentary gives short shrift: Fort Apache, the Bronx and Sidney Pollack’s Absence of Malice. In the former, he plays the beat cop Murphy, who witnesses a crime by a colleague and must decide whether to break the blue wall. In the latter, he portrays a Miami wholesaler named Michael Gallagher who becomes the subject of an investigative journalist (Sally Field) after a union boss goes missing.

Neither is a great movie, especially the police picture (Absence of Malice could’ve been with a better third act). But if you pay attention to Newman, you’re treated to the kind of acting he only aped before—including two of the most searing depictions of grief put on screen. Like Brando in The Godfather (1972)—who by this time had become bloated and beaten by his own tragedies—he exudes a presence so powerful you feel him even when he’s off camera (now that’s ‘perezhivanie’). The tortoise has won; he wears these characters like his skin, so deeply has he merged with them. Far from duplication, he discloses new shades of himself. He goes beneath Shaker Heights, rather than trying to run from it: he takes that emotional Republican and gets under the hood.

In the films of this period, Newman neither strains for idiosyncrasy nor succumbs to non-acting. Instead, his bottled up anger has melted, leaving a serene personality that both purrs along intently and discharges ecstatic bursts of emotion. This is the Paul Newman etched in our minds—the controlled, relaxed gray fox who conveys bone-deep wisdom wrung from suffering. The chasm between this inner zen and the ambitious striving of his youth feels so vast you struggle to bridge it in your head. So did he—Hawke includes a clip of the elderly actor watching a TV interview he gave at 33. “I don’t know that guy,” he quips, jaw ajar, as his alter ego yammers on about resisting the morality of the herd. “I hope he’s happy.”

As you take in the documentary, you’re aware of Hawke working out his own relationship with art and fame—one star excavating the mystery of others. Unfortunately, he injects himself into it all too often. What’s worse, he can’t settle on a thesis and tells you what he wants to say rather than show you. He explains, for example, the images of Paul’s accessories fetching a fortune at auction, rather than letting the shots speak for themselves. He claims that The Color of Money captures Newman’s essence, but says the same about other films. And he doesn’t give the man his due for his inventive, flamboyant turn as Gov. Earl Long in Ron Shelton’s comedy Blaze (1989) or his appearance in the neglected film noir Twilight (1998). Instead, he covers the couple’s many collaborations over the years. This makes sense given that his remit was to craft a dual biopic. But by relying on the family (even grandchildren) to provide color, he sacrifices critical distance.

The picture turns syrupy as a result, trading on the public affection for Newman and Woodward in their twilight. Where are the film scholars to provide analysis? Without such learned voices, the movie fails to do right by its subjects. These mistakes, however, go hand in hand with Hawke’s intelligence and fulsome aesthetic capacities. Like Newman, he became a star before learning to act, but in middle age has turned into one of the most vulnerable, daring, unpredictable male performers of his day (witness him in Born to Be Blue [2015], First Reformed [2017], and Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise trilogy). His 2018 picture Blaze—a beautiful, unheralded movie about a doomed Texas musician—displays lyrical directorial vision and virtuoso technique.

He’s at his best here when he repurposes (and at times improves upon) Paul and Joanne’s movies to sculpt his own. He creates many moments that linger in the mind, such as when Paul’s first wife describes their divorce as we watch him in The Terrace (1960). Hawke adds a dynamite soundtrack (he’s a jukebox of music) and gets his actors to deliver sharp, soulful voice performances. Casting Clooney—perhaps the closest thing we have to classic Hollywood left—as Newman is a particular stroke of genius. He does much better with the latter part of Paul’s career, and he regains his footing in the final episode.

By the late ‘80s, Joanne and Paul had played so many scenes together—at the office and at home—that their passion had turned to peace. They aged gracefully, growing past the resentments of middle age to enter a second springtime. After a dozen TV series and movies, she notched a comeback as Amanda in Paul’s lovely 1987 adaptation of The Glass Menagerie (with John Malkovich and Karen Allen). And again in 1990 opposite her husband in the otherwise dull Mr. and Mrs. Bridge. More importantly, she became a guru in her own right, mentoring the headliners of the next generation—among them Allison Janney, Dylan McDermott, and Linney. (Linney voices Joanne and brings their intimacy to bear on her delicate line readings.) She gave it to them plain and simple:

You can’t be an actor unless you’re willing to make a fool of yourself. You’ve got to love the process.

As an emissary for Stanislavksi’s real system—not to be confused with stunts like gaining (or shedding) fifty pounds—Woodward left a lasting legacy. Thanks in no small part to her, the rumors of the Method’s death have been greatly exaggerated.

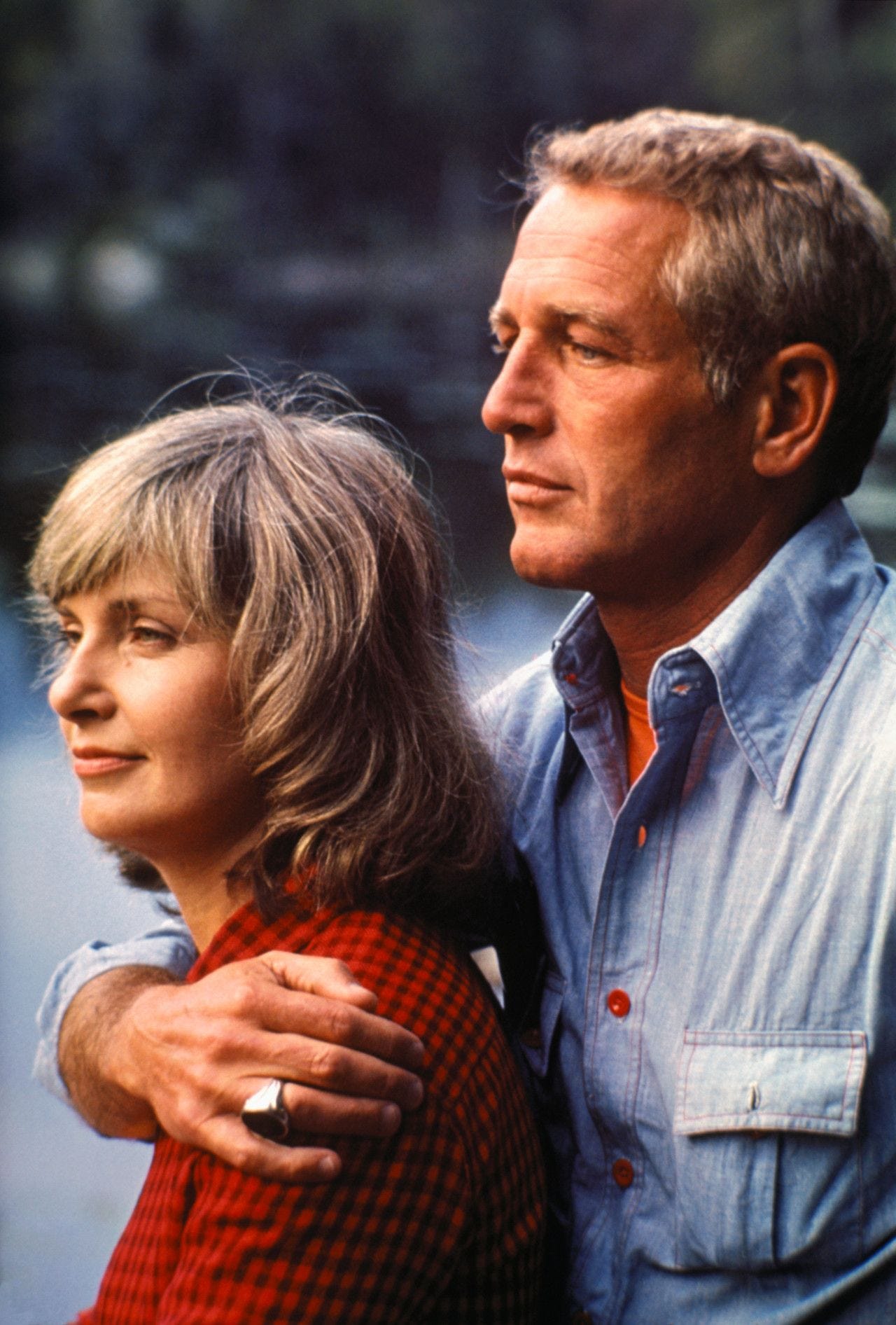

Screenwriter Robert Towne observed that what makes great actors great is their capacity to be photographed well. By that, he didn’t just mean they look gorgeous on camera (although Joanne and Paul certainly do). He also meant the way their faces, even in repose, reflect hidden currents—still waters run deep. By the late middle of their lives, Paul and Joanne’s eyes were windows to contemplative souls. Hawke provides a wealth of scrapbook photos, home movies, and audition outtakes to assemble his subjects, like a collage. They were part of the era of American film when the actor’s image saturated the populace and shaped our ideas of society, art, and ourselves. They became nostalgic figures by the end, incarnations of a national innocence that felt corrupt at the dawn of the millennium. This golden age—for the country and the couple—was a myth, of course, and Hawke shows you something richer: the baggage that burdens prodigies.

Yet the myth endures. When Paul passed in 2008 at 83, the wave of sorrow that attended his loss spoke to the grip it still exercised. Five years before, he appeared onstage for the first time in almost half a century, as the Stage Manager in Our Town at Joanne’s Westport Country Playhouse. The production (which you can watch online) highlighted the two at their best: a creative partnership forged in respect. When he answers Emily’s question at the end—“Do any human beings ever realize life as they live it, every, every minute?”—you feel your heart crack, both from Wilder’s lines and Newman’s frailty. He and Joanne weren’t saints, thank God. But when the Muse found them, poets they were. You walk away from Hawke’s film charged by the sense that—in moments both onscreen and off—they realized life.