Apocalypse Now

What is the Book of Revelation?

I. The End Is Nigh

Revelation 4 (from The Bible Experience): The Throne in Heaven

Well, it’s November, the last month in the Christian liturgical year and, fittingly, the month in which the church remembers the dead in a special way. The readings from the lectionary these days all deal with the end—the end of the year, the end of our lives, the end of time. This past Sunday’s Gospel, from Luke, gives you a sense of the tenor of this month:

When some were speaking about the temple, how it was adorned with beautiful stones and gifts dedicated to God, Jesus said, “As for these things that you see, the days will come when not one stone will be left upon another; all will be thrown down.” They asked him, “Teacher, when will this be, and what will be the sign that this is about to take place?” And he said, “Beware that you are not led astray; for many will come in my name and say, ‘I am he!’ and, ‘The time is near!’ Do not go after them. “When you hear of wars and insurrections, do not be terrified; for these things must take place first, but the end will not follow immediately.” Then he said to them, “Nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom; there will be great earthquakes, and in various places famines and plagues; and there will be dreadful portents and great signs from heaven.”

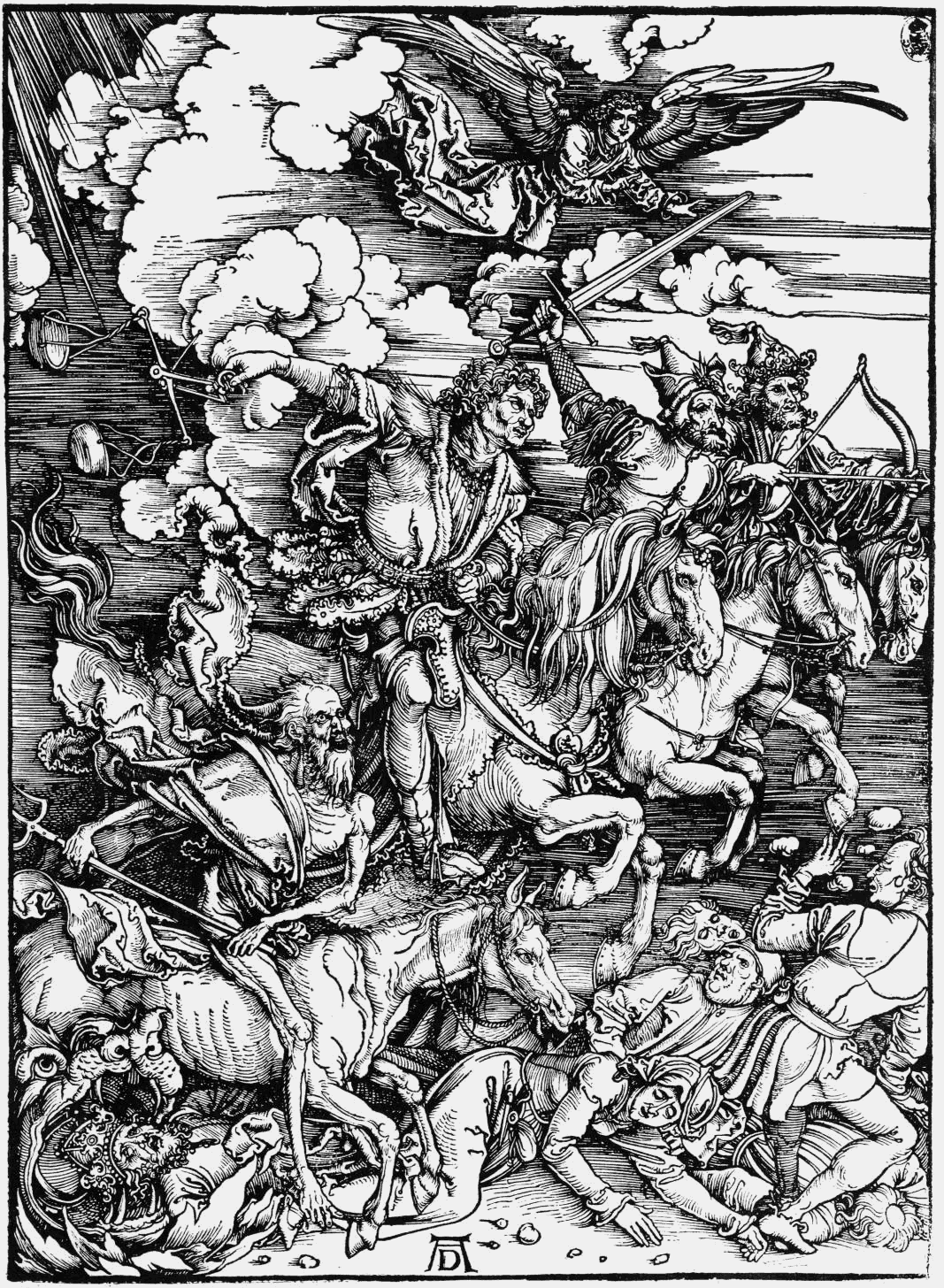

I know what you’re thinking: “What in God’s name’s going on here?” Well, it’s very simple—this is what’s called an “apocalyptic” saying of Jesus. “Did you say apocalypse?” Yes. “Oh, no, that’s all that crazy culty stuff, right? The four horsemen from the Book of Revelation and lakes of fire and all that? Run!” Ok, ok, hold on. Yes, the apocalyptic dimension of the Bible is one of the most strange, terrifying, and abused aspects of the book. Fundamentalists run wild with it, while liberal Christians steer as far away as possible. It seems as if every few years we hear news of some self-proclaimed prophet who’s “studied” Revelation and revealed that the world will end next Tuesday at 12 o’clock. Hysteria ensues, as a few hapless souls get swept up in the fervor. They throw away their livelihoods and even their lives, baffled when the appointed hour comes and goes with hardly a cosmic peep.

Revelation 5: The Scroll & the Lamb

In fact, this very thing happened when I was taking a course in graduate school on apocalyptic literature. During the spring of 2011, radio preacher Harold Camping took to the airwaves in California to proclaim May 21 as the Day of the Lord. His deluded followers did what anyone would do: sold their possessions, even homes, and began driving around the West to announce the coming Judgment. I was sitting in class during these weeks with Dan Harrington, a Jesuit priest and one of the world’s leading scholars of the New Testament. Dan, who’s gone to Spirit now, had been painstakingly leading us through the apocalyptic texts, teaching us what they’re really about. Everyday, we’d check in on how things were going for Camping and his flock. When May 21 passed without the foretold earthquake, we couldn’t help but laugh for the pitiable fools. Didn’t they hear Jesus’s own words? “Beware that you are not led astray; for many will come in my name and say, ‘I am he!’ and, ‘The time is near!’ Do not go after them.”

Revelation 6: The Seals

It’s humorous—and sad. Many people read Revelation and similar passages and think they’re predictions of forthcoming events. The Left Behind series from the early 2000s fed on this millennialist thinking, which dominates much of the American evangelical landscape. Others think these texts must be descriptions of mystical experiences, occasioned by some combination of spiritual fire and psychedelic substances. Maybe John of Patmos was tripping on the island’s magic mushrooms! Fun as that theory is, it’s probably not true. Dante’s Inferno describes astonishing visions, but we don’t believe he actually had a mystical encounter or was doing mescalin. He was playing with language in a symbolic, poetic way, as modernists like Joyce or science fiction authors do.

But if the apocalypse isn’t about engaging in Nostradamus prophesying or dropping acid, what is it? It’s important that we understand. Revelation is the most popular book of the Bible for people incarcerated. That gives us a clue: it’s got something to do with good and evil, hope, and overcoming oppression. Armed with the knowledge Harrington gave me, let me walk you through this fascinating subject.

II. Conventions of Apocalypse

Apocalyptic literature is, fundamentally, literature. It is a genre of written discourse. Like all literary genres, it’s structured around a series of conventions, motifs, and dynamics that the writer utilizes and which we can analyze. It is, at heart, a product of the religious imagination, crafted in language. Its authors were scribes, drawing on a long lineage of apocalypticism, the same way writers in other genres groove off the tropes, symbols, and narratives of that tradition. Their minds weren’t exploding from psilocybin or some trance—they were clear, controlled, and cogent as they played with literary conventions, for the sake of conveying meaning to the reader in a specific way.

Revelation 7: 144,000 Sealed

Terms. First, let’s define some ideas:Apocalypse—“Revelation.” Literally, in Greek, “unveiling.” A literary genre, it includes elements of a narrative frame; angelic or otherworldly interpreters who mediate the experience; and a vision of a transcendent reality either spatial or temporal or both. Literary critic Northrop Frye describes it thus: “The Greek word for revelation, apocalypsis, has the metaphorical sense of uncovering or taking a lid off, and similarly the word for truth, aletheia, begins with a negative particle that suggests that truth was originally thought of as also a kind of unveiling, a removal of the curtains of forgetfulness in the mind. In more modern terms, perhaps what blocks truth and the emerging of revelation is not forgetting but repression.”

Eschatology—“Science of things.” The content of apocalypse, it pertains to a hope or expectation of a new order either in this same world or in an entirely new world. Includes ideas of resurrection and last judgment. Prophetic eschatology looks forward to a renewed Israel.

Proto-apocalypse—Early phases of apocalyptic literature. The hopes it expresses are still this-worldly.

Apocalypticism—Various historical movements constituted by eight motifs:

Urgent expectation of the end of earthly conditions in the immediate future.

The end as a cosmic catastrophe.

Periodization and determinism.

Activity of angels and demons.

New salvation, paradisal in character.

A manifestation of the Kingdom of God.

A mediator with royal functions.

The catchword glory.

Revelation 8: The Seventh Seal & the Trumpets

Matrix. Apocalypse is not simply a conceptual genre of the mind, but is generated by social and historical circumstances. What was the historical, social, and compositional setting for these writings?

Historical Setting: The dawn of apocalyptic should be located in post-exilic prophecy in the late sixth century B.C.E. This was the period in Israel’s history known as the Babylonian Exile, when they’d been conquered and taken into captivity in what is today Iraq. While there for decades, the Israelite scribes engaged with Babylonian literature and its emphasis on dreams and visions. They were also exposed to Persian dualism. Later, after returning to Jerusalem, they were conquered again by the Greeks. This brought them into contact with Hellenism, in the 4th Century B.C.E.

Social Setting: As implied above, these writings arise in a context of political distress and oppression. A key feature in early apocalyptic literature, then, is nostalgia for an imagined past and alienation from an intolerable present.

Compositional Setting: The composition of highly symbolic literature involves a vivid use of the imagination, which can be difficult to distinguish from visionary experience. Similarly, the apocalyptic authors may have felt an intense emotional kinship with their pseudonymous counterparts, while still being aware of the fiction involved. Even shamans have to learn the cosmology and mythology of their ascents before they can ‘experience’ them in ecstasy.

Revelation 9: The Falling Star

Language

Apocalyptic writings come from the language of the Hebrew Bible. In a sense, the entire Bible is full of hope that something better will come about. Many Prophets speak this way, and apocalyptic literature takes their themes and language and goes to town.

An element of mystery and indeterminacy constitutes much of the atmosphere of apocalyptic literature. In reading it, we should allow several concurrent identifications to play in our mind. The texts achieve their effect precisely through the element of uncertainty. They have a highly symbolic and allusive character. Apocalyptic literature isn’t governed by the principles of Aristotelian logic; it’s closer to the poetic nature of myth.

The insight that the apocalypses did not aspire to conceptual consistency but allows diverse formulations to complement each other is especially important. These texts utilize expressive language, articulating feelings and attitudes rather than describing reality in an objective way. This allusiveness enriches the language by building associations and analogies between the biblical contexts and the new context in which the phrase is used. We should focus on the illocution of the text, or that which it does in saying what it says. Exhortation and consolation are typical illocutions of apocalypses.

Revelation 12: The Woman & the Dragon

Form. What shape do these writings take?

Transcendent Journey: There are two strands of tradition in Jewish apocalypses, one of which is characterized by visions—with an interest in the development of history—while the other is marked by otherworldly journeys with a stronger interest in cosmological speculation. The form of apocalypses involves a narrative framework that describes the manner of revelation. The main vehicles of the revelation are visions and otherworldly journeys, supplemented by discourse or dialogue and, occasionally, by a heavenly book. The constant element is the presence of an angel who interprets the vision or serves as guide on the otherworldly journey. This quasi-divine figure indicates that the revelation is not intelligible without supernatural aid—it’s out of this world. In all the Jewish apocalypses the human recipient is a venerable figure from the distant past, whose name is used pseudonymously. (Dante picks up this trope in Inferno, where his alter ego is led by Virgil into Hell.) This device adds to the remoteness and mystery of the revelation. The disposition of the seer toward the revelation, and his reaction to it, typically emphasize human helplessness in the face of the supernatural. The revelation of a supernatural world and the activity of supernatural beings are essential to all apocalypses. In all there are also a final judgment and a destruction of the wicked.

Cosmic World View: In apocalypses, the world is mysterious and revelation must be transmitted from a supernatural source, through the mediation of angels. There is a hidden realm of angels and demons that is directly relevant to human destiny, and this destiny is finally determined by a definitive eschatological judgment. In short, human life is bounded in the present by the supernatural world of angels and demons, and in the future by the inevitability of a final judgment.

Apocalyptic Eschatology: All apocalypses involve a transcendent eschatology that looks for retribution beyond the bounds of history. In some cases this takes the form of the judgment of individuals after death, without reference to the end of history.

Revelation 13: The Beast of the Sea & the Beast of the Earth

III. Meaning

Revelation 14: Harvesting the Earth & Trampling the Wine Press

Apocalyptic literature conveys three major ideas:

It is the literature of the oppressed.

It is the literature of the imagination.

It is the literature of hope. Hope must have an object; there must be a reason to hope in it; and it must have a possibility of coming true.

Apocalypses are intended for a group in crisis, exhorting and consoling them by means of divine authority. Whatever the underlying problem, it’s viewed from a distinctive apocalyptic perspective. This perspective is framed, spatially, by the supernatural world and, temporally, by the eschatological judgment. The problem is not viewed simply in terms of the historical factors available to any observer. Rather it is viewed in the light of a transcendent reality, disclosed by the apocalypse. The function of the apocalyptic literature is to shape one’s imaginative perception of a situation, and so lay the basis for whatever course of action it exhorts.

Revelation 15: Seven Angels With Seven Plagues

In pursuing this goal, apocalyptic literature employs a number of rhetorical features and theological devices:

It attempts to persuade by the power and beauty of its vision.

It includes edifications as a feature of theological discourse.

It has a polemical and argumentative side. It’s prepared to say no to a secular culture that says no to Christianity.

It’s inherently a diagnostic of deficient and insufficient forms of Christianity.

It both recommends and comments on practices in which vision is made flesh in witness and forms of life that are exemplary.

It moves towards a condition of ecstasy and anagogy, because its discourse is of our future with God.

It uses famous names from Israel’s history to receive the revelations of what is to come. These are persons of real authority, pitted against the claims of the present false leadership.

The revelation is secret and must be kept until the events come to pass.

The language is always highly symbolic and can be decoded only by the elect.

It uses prophetic prediction to give authority to the words of revelation that are received.

The real authors of these books are anonymous even though they often use the name of famous people of the past to lend weight to their books—figures such as Enoch, Moses, Ezra, Baruch, Isaiah, etc.

Revelation 16: The Seven Bowls of God’s Wrath

Besides these major characteristics, other elements appear regularly in one or more known apocalypses:

Pessimism about the state of the world and human ability to change it.

Dualism between the forces of good and evil and a final battle for world domination. The forces of evil are man-made empires (e.g., Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Rome), which are personified by various symbols (e.g., a statue with different metals in the Book of Daniel).

Determinism of a divine plan that is already preparing for the battle against evil and its final defeat.

Confidence in divine intervention on behalf of the oppressed and the righteous who suffer.

Cosmic viewpoint in which the struggle involves the whole universe.

Use of intermediary beings such as angels and demons.

An expectation that old prophecies will be fulfilled for the first time, or in a new way.

Hope in the resurrection of the dead and victory of the just.

Hope in a glorious new kingdom in heaven or on earth in which God will reign over the just while the wicked will perish.

Revelation 19: Babylon’s Fall & the Heavenly Warrior

Finally, there are a few lasting values basic to all apocalyptic thinking:

God is never indifferent to his world, nor is he powerless to intervene for the sake of his name and to achieve justice.

There are important moments in history when we can expect God to act in new ways and not in the same old ways.

Christian belief decisively rejects the power of evil to control our lives and proclaims that death is not the final end for those who are faithful to God. Martyrdom will not be in vain.

We must show a strong trust in God and reject human war and violence in favor of pacifism. God will deliver us when he decides.

This literature stresses passionate devotion to the Kingdom of God, and the urgency of being counted among the just rather than the wicked.

Apocalypses bring the imagery of the last judgment, heaven and hell into Jewish and Christian thinking.

It is to apocalyptic literature that we can attribute much of our present hope in the resurrection of Jesus as a source of life. The apocalyptic writers held the firm conviction that the just will rise to life because God is faithful to his covenant promises.

Apocalyptic literature encourages Christians to attend to oppression and persecution in our world, while nevertheless offering praise to God. It offers a vision of God that suggests that there is much more to do than do enough; that witness even to the point of martyrdom is called for; and that God is the victor over death as well as sin.

Revelation 20: The Thousand Years

IV. The Inner Apocalypse

Revelation 21: New Heavens & New Earth

In The Great Code, his architectonic study of the Bible as literature, Northrop Frye concludes with a brilliant rumination on what he calls the “inner apocalypse.” This is the most important idea to take away from all of this, the notion that gets lost in the frenzy of doomsday movements. The apocalypse is meant to happen now, in our own minds. Like The Beatles at their most phantasmagoric, it’s a revolution in the head. I’ll give Frye the final word:

There are two aspects of the apocalyptic vision. One is what we may call the panoramic apocalypse, the vision of staggering marvels placed in a near future and just before the end of time. The panoramic apocalypse gives way, at the end, to a second apocalypse that, ideally, begins in the reader’s mind as soon as he has finished reading, a vision that passes through the legalized vision of ordeals and trials and judgments and comes out into a second life.

In this second life the creator-creature, divine-human antithetical tension has ceased to exist, and the sense of the transcendent person and the split of subject and object no longer limit our vision. For the author of Revelation, all these incredible wonders in his vision are the inner meaning or, more accurately, the inner form of everything that is happening now. Man creates what he calls history as a screen to conceal the workings of the apocalypse from himself.

The vision of the apocalypse is the vision of the total meaning of the Scriptures, and may break on anyone at any time. It comes like a thief in the night (Revelation 16:15, cf. I Thessalonians 5:2). What is symbolized as the destruction of the order of nature is the destruction of the way of seeing that order that keeps man confined to the world of time and history as we know them. This destruction is what the Scriptures is intended to achieve. The apocalypse is the way the world looks after the ego has disappeared.1

Revelation 22: The Tree of Life

Northrop Frye, The Great Code (136-138).