Baseball Blues

Should We Ban Cheaters From the Hall of Fame? Or Abolish the Museum Itself?

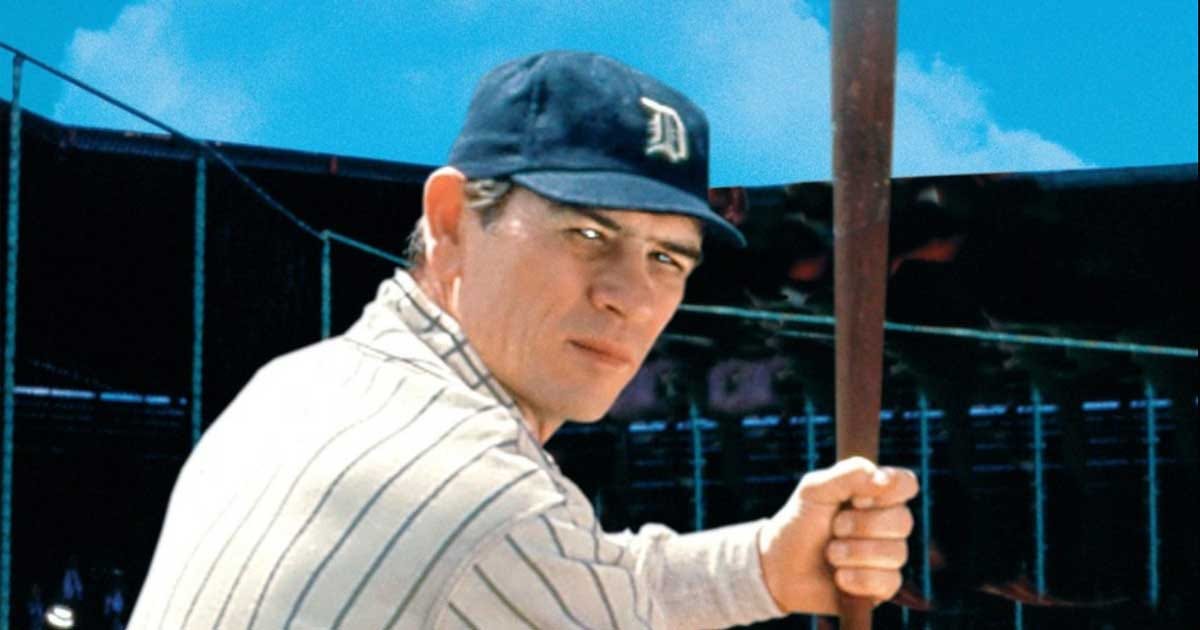

Last month, New York magazine ran an article about whether to admit into The National Baseball Hall of Fame players implicated in various scandals. The most significant of these, of course, is the performance-enhancing drug saga that afflicted the sport from the late-’90s through the mid-2000s. The Baseball Writers Association of America has once again denied stars Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Curt Schilling entry into the Hall. The first two were ostensibly voted down because of their ties to doping, and the refusal was their last shot. They’re ineligible for future consideration (unless the Veterans Committee intervenes).

In his piece, Ben Jacobs raises salient questions around the health of the Hall. Tyler Kepner highlights even more in recent reporting for The New York Times. The PED scandal has broken the institution, Jacobs argues, as the guardians of the shrine struggle to make the choices demanded by the moralists of our age. Do you admit dopers? How can you ban them when questionable players from the past are already enshrined? More than most, I have a stake in this debate. Not only am I a fan, I was born and raised in Cooperstown itself. My family were friends of the Hall’s president, and I even had a summer job there in high school (I recall giving a private tour to pitcher Don Sutton and his kin—nice people). I’m personally invested in these decisions, since they bear on the future of the village I call home.

My views on this issue have shifted over the years. I used to think, Just let these players in and create a permanent wing in the museum about the drug culture they took part in. Name the men involved in doping and display their faces on the wall. Hell, engrave right on their plaques that they were taking PEDs. That could be the compromise: you're in the Hall, but your name’s forever associated with drug use. This is more or less the realist position that Zev Chafets stakes out. As does Jeff Levitsky. The latter investigated Bonds, Clemens, and other stars from the steroid era and claims they should be let into Cooperstown, since their behavior was part of a larger failure of baseball. Yet I've been thinking more and more and this proposal seems wrong to me now—my heart has hardened.

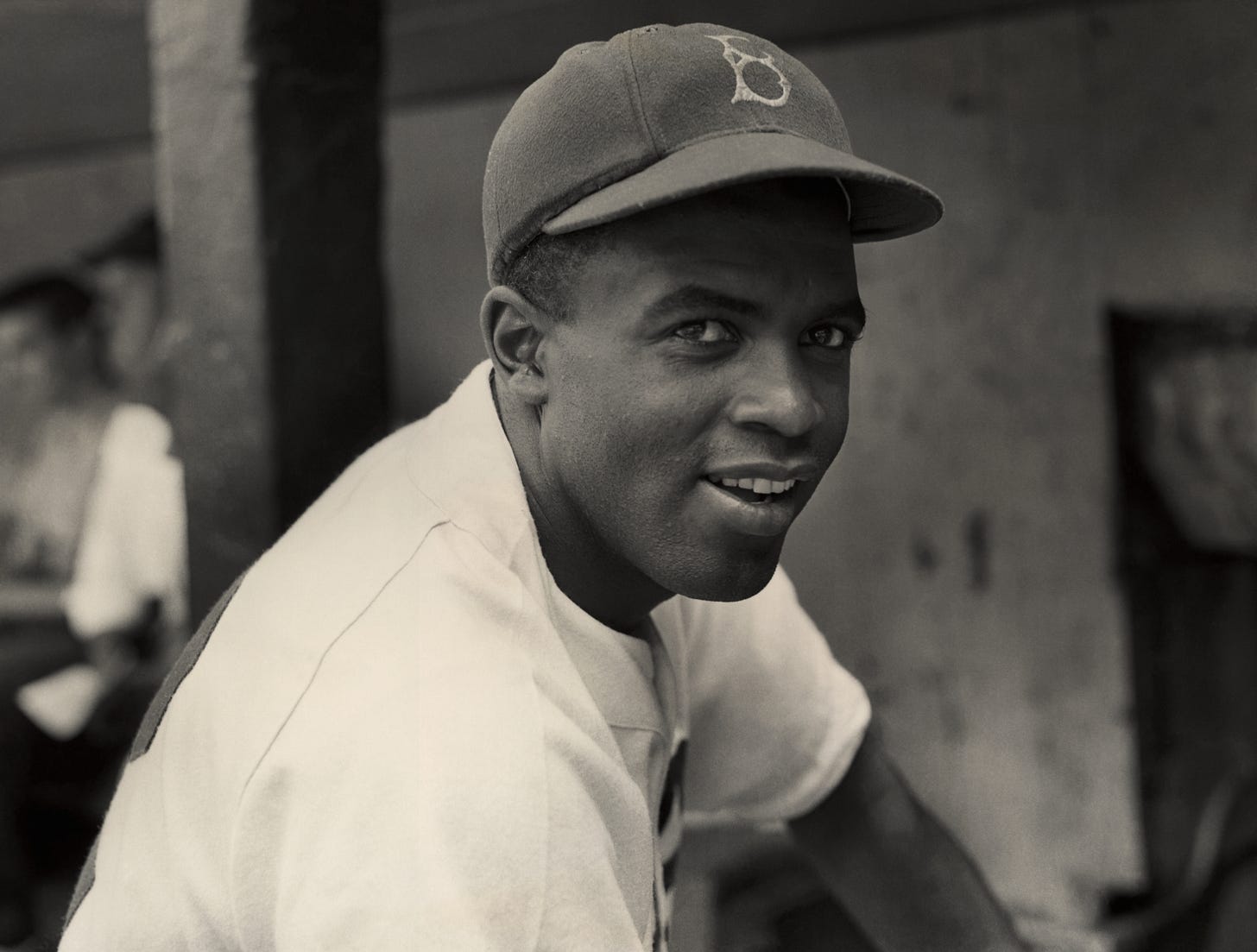

Think about the response to PEDs in other sports. Lance Armstrong had his Tour d'France victories stripped when he at last admitted that he doped—a pervasive practice in cycling. Olympians like Marion Jones have had their medals revoked and their records erased for the same reason. Jones was part of the very BALCO scandal that Bonds was—except she confessed her crimes to the authorities. For that cooperation, she was rewarded with a jail sentence—a reckoning that Bonds and Clemens evaded.

In fact, Clemens had the gall to go before a congressional committee—of his own volition—and lie about PEDs, throwing his former trainer under the bus (a stunt Jacobs, incredibly, doesn't mention). He even backstabbed his New York Yankees battery mate Andy Pettite, who confessed that the two doped for years. Clemens not only used drugs, but pushed them on Pettite. The only reason he didn't get convicted of perjury was because he paid big shot lawyers to thwart the prosecution.

That behavior alone should have disqualified him from the Hall. Our prisons are crowded with people guilty of less. Say what you will about Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Rafael Palmero, but at least they admitted to using steroids before the same committee. Clemens is such an arrogant asshole that he felt accountable to no one—including Congress, the representatives of the American people. And now we’re supposed to feel sorry that he’s been denied the Hall? Who the hell does he think he is?

Ok, you might reply, we should keep him out. But in the case of Bonds, Alex Rodriquez, and others, they weren't doing anything at the time that was banned. They were part of a culture of drugs—almost everyone was using. This is the argument of Levitsky and Chafets. Fair enough. It's wrong to single these guys out for criticism. But do we use such logic in any other area? The Catholic Church had a culture of child sexual abuse for centuries, but the church shouldn't just shrug that off and canonize abusers (although in the case of John Paul II, it’s done so for their enablers). Society demands justice.

Similarly with these players. What they did is not on the level of sex abuse, obviously. But they're lucky when you compare them to Armstrong, Jones, and athletes in other sports. No one’s decided to strip their records and awards—their World Series rings, their MVPs, their Cy Youngs. We're not going after the millions they made for the invaluable skill of hitting a ball with a stick. Few want to bar them from the game or throw them in the brig. We're simply denying them honorary induction into a private museum—one that’s a privilege, not a right. There’s a difference between not punishing a player and actively rewarding him.

It’s easy for me to say this. Growing up, my greatest heroes on the Yankees were Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, and their manager, Joe Torre. (I’ve written glowingly about their dynasty.) All three were elected into the Hall; they strike me as not only worthy performers, but respectable men. Perhaps I’m naive. But neither Jeter or Rivera has been linked to PEDs, which should give apologists for dopers pause. If the drug culture was a matter of course, too powerful to resist, how do you explain the sobriety of these players? Shouldn’t they be the very ones we applaud—for their integrity as much as their stats? On that score, their clean play didn’t hurt their performance: Rivera was the most dominant closer in history. Jeter accrued the sixth-highest number of hits.

I’m not claiming they’re pure—Clemens and Pettite were on their team, so they benefited second-hand from the drugs. And what did Torre know about steroids in the clubhouse? Maybe down the road historians will produce revelations that finger Rivera and Jeter. I’d be disappointed. But I’d hold them to the same standard. If this means an even tinier number of players make it into the Hall, so be it. And before you jump down my throat, I know: the BBWAA just elected David Ortiz into the Hall. Ortiz—who tested positive for steroids, denied it, and (despite his gregarious reputation) evinced checkered behavior on field. The excuses made for him—often from the same quarters that denounced Bonds, Clemens, and the rest—baffle me. What can I say? It’s rank hypocrisy and should never have happened. Be better, baseball.

All of these issues raise a bigger question—what exactly does the Hall of Fame celebrate? Athletic excellence alone? Or something more expansive—sportsmanship, cultural contributions, your impact on society? The more I think, the more I believe the Hall must be about the latter, not just the former. It should be clear to players from day one that entry is about not just your performance, but your character: as an ambassador for the sport, a citizen, a human being. You don't have to be the second coming of Christ. But you do have to meet a basic standard of decency. The Hall already instructs the voters to consider “integrity, sportsmanship, and character.” Good. If you want to be a sexual harasser like Omar Vizquel or gamble on your team like Pete Rose, fine, go ahead (actually, please don't). If you're great, our sycophantic culture will turn a blind eye and reward you with fame and fortune. But you will not be immortalized as some legend.

Unfair? Perhaps. After all, many figures are in the Hall who cheated, played dirty, and worse. Should we remove their plaques like Confederate statues? At the moment, I don't think so, and I realize that’s a contradiction. We can’t undo past decisions. I'm uncomfortable with cancel culture and nullifying the achievements of people when we find out that, guess what, they're sinners like you and I. My favorite painter, Caravaggio, murdered a man in a bar. Should I not contemplate his paintings? Martin Luther King, Jr. was an adulterer—does that invalidate the good he did? No. We can appreciate the triumphs of people while also admitting their crimes. Only God can judge. If dirt’s dug up on past Hall of Famers, we can do what I suggested before and put such information in the museum’s galleries. Such transparency would help end the hagiography around these men, the kind Ken Burns indulged in with his 1994 documentary.

So on that note, I don’t want to airbrush Bonds, Clemens, and A-Rod out of history. We can forever appreciate their skills, watch their highlights, savor their records—with eyes open about their doping. I just insist they not be installed in a pantheon of demigods. Remember: the institution comprises two sections, a museum, and a rotunda that houses the plaques of 340 players. Most players never get in the latter, but many are discussed in the former. In other words, we can document the achievements of juicers in the galleries without installing them in the Hall proper. We can tell the story of the game—warts and all—without anointing cheaters. The choice between acknowledging the flawed history of the sport and deifying dopers is false.

What would it say about baseball if they did get plaques? That you can cheat your way to glory as long as no one got hurt and almost everyone else was doing it? Think about the message that sends. Yes, they would’ve amounted to amazing players even without those drugs—that's the tragedy. But we can't deal with counterfactuals—we have to deal with what actually happened. And it only underscores the point: cheating isn't worth it. This isn’t meant to preserve a Golden Age of baseball that never was—it’s to endorse a higher set of values for the future.

So many of these jocks carry around massive egos, what with the attention and money we lavish on them. Maybe it's time we changed that—by making entry into the Hall of Fame based on the requirement that you don't live a narcissistic, self-indulgent, hedonist life. Or at the very least, that you don’t dope. On that score, perhaps we should induct players who were marginal on the field but solid people. There are a lot of them, I suspect. Wouldn't it be better if every schoolboy could recite the charitable actions of a player, rather than his ERA? Or if we honored courageous souls like Colin Kaepernick, instead of blacklisting him? Or pitcher Zack Greinke for his triumph over depression and anxiety? We say it to our kids all the time: it's not about whether you win or lose, it's how you play the game. Well, maybe we should apply that message to adults.1

Don’t think I’ve forgotten about management and ownership, by the way. They’re just as guilty as the players, if not more. How does the BBWAA justify electing former commissioner Bud Selig into the Hall? He presided over the steroid era and the Mitchell Report concluded that he bore as much responsibility as anyone else for the drug abuse. Yes, he revived the league after the ‘94 strike and introduced revenue-sharing, a baby step toward economic democracy. But that’s not earth-shaking. For decades, owners have gorged themselves at the public trough, off-loading the costs of for-profit stadiums onto hapless citizens. They conduct their business like the ruthless robber barons they are. I’m with Ben Burgis: we should nationalize the clubs and turn them into public organizations. We call baseball our national pastime—let’s make that a reality.

Which raises another question: who makes the call? Why is it that induction into the HOF is determined by a cabal of writers unanswerable to the public? Their process is enshrouded in mystery, like the Oscars. How do they vote? What's their criteria? I'd be in favor of creating a transparent process for making these decisions. Something akin to the citizens' assembly model I favor in government. Have a group of fans, former players, and officials come together by lottery each year and hear presentations from experts about candidates, going over the case for why they should or shouldn't be inducted. Then let the assembly deliberate and come to a consensus. Because that's the only way to address the questions at play here. The Hall can't answer them, the writers can't, the MLB can't. And if they try, they'll look like what they are—a priestly cult issuing dictums. If we’re going to maintain an exclusive club of elites that caters to their every whim, let’s at least make the process democratic. Fans are the only reason ballplayers exist—give them the final say.

Jacobs’s article gets at a larger pathology—all around, we see our institutions buckling under unprecedented stress. Baseball's one of them. Contrary to what Gregory Hill argues in Commonweal, the sport’s really in trouble. Freddie deBoer has an excellent post about the problems that plague our national pastime. Plummeting attendance, lack of action, games longer than it takes to read War and Peace. I’ve neither the time nor the attention span to watch nine innings at this point in my life. I drop in for the playoffs because those contests have high stakes and generate excitement. But the regular season asks a lot of you. The ball’s barely in play anymore, and there are rarely runners on base to try tactics like a steal or hit-and-run. The game’s obsessed with homers and strikeouts to the point that little else happens. Maybe that's the real failing of McGuire and company—they introduced the era of the long ball, and it's ruined things. Let’s try to induct players adept at skills other than blasting bombs and ringing up Ks.2

Or should we? The more you think, the more you wonder about the very purpose of a Hall of Fame at all. What’s this for, in the end? I enjoy sports as a fan and player, and baseball’s still up there for me, despite its troubles. But we already fetishize athletes to an unhealthy degree. Same with movie stars. They’re modern royals, complete with entourages and glitzy consumption. Isn't it enough that they become rich and famous? Why invent more accolades to give them and build a “Hall of Fame” that functions like Mecca? (Except Mecca is where you worship God, not men.) Is this really what we should spend our time and money on? I’m all for museums that preserve the cultural enrichment that baseball or basketball or movies or whatever provides. And in those places we will of course tell tales of the greats. But we can also acknowledge their flaws, keeping their feet on the ground instead of boosting their head into the clouds. Making idols of people—whether politicians, artists, or sports stars—is dangerous, especially in a republic.

You may say that, once again, I'm being inflexible and idealistic. I know. We live in a fallen world, an unjust society. Pro athletes suffer hardships despite their outsized pay—they’re hounded by the media, crushed by fans, under intense pressure to succeed. And athletes have forever sought an edge on their competitors, which shades into cheating. If Chafets is right, baseball was awash in players who altered their bodies, minds, and equipment with substances of all sorts. For all we know, the ancient Greeks used concoctions to gain an advantage. As long as we have sports, we will have such behavior. Don’t expect more of athletes than we do of others. They entertain us—let them do what they want. And where do you draw the line between natural training and artificial enhancement? What’s the difference between transforming yourself with weights and diet and wellness fads—like Tom Brady’s goop regimen—and anabolic steroids? How do you distinguish between sports medicine and cyborg-science?

There’s weight to all this. I don’t have great answers. But realism can curdle into cynicism, and that becomes corrosive. To whom much is given, much is expected. We want better behavior from our leaders and business sector. Why not athletes? We differentiate between politicians who raise campaign contributions and those that take bribes. Both are unsavory, but one we’ve made unacceptable. That may provoke laughter given the graft of 19th-century politics, and I’m all for stricter rules. But it only underscores my point: society advances, institutions reform, and mores change. We have to start somewhere.

Again, look at the discipline imposed on Olympians. On a gut level that we struggle to explain, we feel there’s a difference between hours in the gym and the injection of drugs to get jacked. Why’s the latter better than shots that masks pain? Or surgery that repairs tendons? Or vaccines, for that matter? Hard to say. Maybe because those medicines restore the body to baseline and ward off disease. Maybe it’s just a question of degree rather than kind, a line we draw knowing it’s arbitrary and fluid. If one day (and it’s coming quick) we invent microchips that give batters the eyes of the Hubble telescope or pitchers the arm of a catapult, we’d agree a boundary’s been crossed. On that note, perhaps we just create separate leagues, one for players who dope and one for those who don’t, akin to the Paralympics.

I don’t mean to moralize or pass ammunition for the drug war. I’m not Nancy Reagan. Like all adults, I ingest chemicals on a regular basis—medicinal and recreational, synthetic and organic. I’m writing this essay with the aid of coffee, a drug that warps consciousness itself. I don’t consider baseball juicers beyond the pale. Admit it, apologize, and let’s move on. Nor do I denounce the use of PEDs by everyday people. If you wish to use steroids and other substances, go ahead. It’s your body—you know the risks. But when it comes to judging official competition, we have to erect a higher bar. Otherwise it would render statistics, records, and the very concept of winners and losers meaningless. Unless we want to return sports to an amateur affair pursued for pleasure (which might not be a bad idea) we’ve no choice but to enforce a drug policy.3

If you’re the player “unlucky” enough to suffer the consequences of the new standard, well, tough shit. You got to play a game as your job and make bank. If you feel wronged, go home to your mansion and count the Benjamins. The world’s tiniest violin will accompany you. Afghanistan is starving and half of Americans don’t have enough money to pay an emergency $500 bill. To reiterate my position, I wouldn’t call on the MLB to purge records, expunge titles, or confiscate salaries of dopers. I simply say this: don’t induct them into the Hall. If drug use was a product of a corrupt system and lax enforcement, then let's change the incentive structure. The HOF could set an important precedent in this respect.

Then, of course, there's the question of whether the Hall of Fame is healthy for Cooperstown itself. Having grown up there, I know well the damage it's done. This bucolic slice of creation has weaved quite a tapestry, from James Fenimore Cooper to the Glimmerglass Opera to Otsego Lake. Yet each summer, the 1,900 residents are held hostage by the Hall and the legions it draws. It wasn’t always so. When my parents moved there around 1980, Main Street hosted an assortment of mom-and-pop establishments. You could do your errands, eat lunch in the diner, and stroll the park. Your kids all attended the same school, and the prominent hospital attracted doctors and professionals to dwell in the colonial, Greek revival, and Victorian homes.

Today, downtown stands gutted, taken over by tacky card shops and Little League tournaments. Locals avoid the business center, the sidewalks choked with loud, obnoxious tourists. Most of the money they spend lines the pockets of memorabilia dealers from out of state. Little flows back into the community. But the town’s become dependent on the Hall. Unless you work in the tourist sector or the hospital, it’s hard to make a living. Many young people leave, never to return. My siblings and I would love to move back, yet economic opportunities are limited. Most residents have learned to stop worrying and love the bomb; come Memorial Day, they rent out their properties and skip town. Mammon reigns. As a symbol of late-American capitalism, Cooperstown—like baseball itself—is a cautionary tale. Monocultures destroy the soil and destroy people.

How did this happen? For generations, the town’s benefited from the generosity of one philanthropic family, the Clarks. To this day, heiress Jane Clark carries on the tradition of noblesse oblige. She preserves the village’s image, promotes its institutions, and funds college scholarships (I received one myself). Back in the 1930s, her grandfather, Stephen, wanted to put Cooperstown on the map. Baseball was king, and he decided that was the town’s ticket. He lobbied hard and convinced the MLB to build a Hall of Fame in this sleepy backwater (the legend of Abner Doubleday was a convenient fiction).

I thank the Clarks for all they’ve done. But looking back, that may have been the worst decision in the village's history. Not because it failed—the opposite. It's become a victim of its own success, turning a charming idyll into Baseball Land. It’s still a lovely place to visit and live in. Its natural beauty is attractive and it suffers some of the least political polarization in the country. Yet speaking as a native son, I'm at the point where I'd like to see the museum moved—to Pittsfield, MA, or Hoboken. You know, where baseball was actually invented. It's hard to say this, because there's a certain pride that comes from boasting the institution. It was the first and noblest of the Halls of Fame. Cooperstown evokes national nostalgia. But I'd rather see my home restored than strangled by perverse commerce. At the very least, we should keep the museum but rethink the Hall.

As for most devotees, baseball's about the personal memories I associate with the sport: my favorite players, teams, and victories. And the memories are shared. They're of my family enjoying those games together—going to Yankee Stadium with my mom for the World Series; shuttling between the TV and my dad’s study to relay updates when games got unnerving; staying up to watch nail-biters with my siblings. No museum could replicate those moments—each of us carries them as part of our story. It's enough to enjoy them in private. I guess that's my prescription in the end: let each fan make a separate peace.

It's a little tougher with Curt Schilling—it doesn't sound like he's accused of drug use, just of being a reactionary stooge. I don't think we should punish someone for his political beliefs, however abhorrent. But of course beliefs fuel actions, and maybe he's crossed a line by supporting proto-fascists and threatening the lives of the baseball writers. I haven't studied his case, so I can't say. I never liked the guy; he’s an astounding megalomaniac. And of course he broke my heart as a Yankees fan both with the Diamondbacks and the Red Sox. Nevertheless, his example is a harder one to weigh.

It could be worse. It could be football, a barbaric activity that must be abolished. How can anyone still watch or attend the NFL, after what we’ve learned about the sport’s destruction of the brain? I mean, what’s the difference really between football and the gladiatorial combat of ancient Rome? That the former kills its competitors after they’ve retired, instead of right before our eyes? That hardly makes it superior. It might even be worse—at least the Romans were up front about what they were doing: watching warriors slaughter each other for kicks. We carry on like there’s nothing to see, a culture of denial and deceit. Ok, football doesn’t intend to kill its athletes. But the effect is too close for comfort. Yes, I tuned in to the Super Bowl on Sunday and enjoyed it. I’m a hypocrite. Yet every time I turn on the sport, whether college or pro, I feel a pang of guilt—I’m enabling an inhumane practice. And if you think that’s harsh, ask yourself one question: would you let your child play?

What about other areas? Like students who take Adderall to ace tests, a scenario Chafets throws up? Should they have their results thrown out? Yes! Jesus, is this a meritocracy or not? And don’t cry to me about artists and musicians using substances to boost creativity—apples and oranges.

Thanks Nick this is a thorny issue. So topical with the recent Russian ice skaters positive test for a banned substance.if anyone believes she mixed up this pill with one of her grandfathers there is a bridge want to sell them. I like your idea of a separate wing for the drug years and/or noting it on their plaque. It was so much a part of baseball for such a long time how best to remember it? I do like the idea of keeping the museum. So much rich history to preserve. And surely there is a case to be made for moving it but good luck with that. I hope you get some comments from others from Cooperstown. I wonder how they feel about that. I like the variety of subjects you write about. Reading them is a fun way to start the day.