Here Comes Everybody

Democracy for All

I. Ill Fares the Land

Yves Sintomer is unknown to most Americans, but he’s a leading light among political philosophers of our time. A visiting scholar at Harvard presently, the Frenchman’s latest book, The Government of Chance: Sortition and Democracy from Athens to the Present, immediately takes its place as the single best book on democracy in at least three decades. A work of synthesis, it compresses between its covers all scholarship on the subject in recent years, moving effortlessly between history, theory, and praxis. In sweeping fashion, it stretches back two and a half millennia and brings you right to our present moment. And it does so with clarity of thought and vivacity of style. If you’re searching for one volume to orient you to the terms of debate within the study of democracy and government, look no further.

He begins in medias res, with the current crisis of liberal governments around the world. Thirty years after the end of the Cold War and the halcyon days they foretold, the body politic of the west lies palsied and febrile, beset by the doppelgängers of decadence and discord. Sintomer offers a double diagnosis of post-democracy and authoritarianism, which together constitute a third stage in the evolution of electoral representative government (after the elite early phase and middle stage of mass politics):

Post-democracy, coinciding with the return of chaos capitalism, has seen the emergence of global power centers outside of political parties, in many cases more influential than the state itself. Corporations; stock exchanges; credit rating agencies; arbitral courts; international monetary organizations; and technocratic bureaus make up these phenomena, which have forced leaders to knuckle under and do their bidding.

Authoritarianism has subsequently fed off the resentment of the middle class toward these new gods; it takes their feeling of being squeezed and blames it on enemies both inside the nation and beyond its borders. The rise of populist movements has followed the evisceration of the working class as a united group and conscious identity, its members abandoning their traditional networks and organizations for the embrace of the strongman, or just opting out entirely and dying deaths of despair both quick and slow.

The endgame to all of this was manifested on January 6th, 2021, with the storming of the Capitol in a tragicomic self-coup. Sintomer bluntly sums up the state of affairs:

At a global level, the prognosis for liberal [regimes] at the beginning of the 2020s is not a positive one. Compared with the two previous decades, there are many fewer governments that engage in democratic innovation. A lot of regions are experiencing downward spirals and the number of failed states is growing…Unless serious progressive actions are taken in the Global North as in the Global South, post-democracy and authoritarianism—or even worse, state collapse—are the most probable outcomes.1

Winter has come for the west. Yet beneath this political deep freeze, a soft springtime flowers: the rebirth of democracy by lottery. Since 2004, a wave of citizens’ assemblies has swept the land, with thousands of everyday people selected to make policy decisions both great and small. But though it looks new, this brand of citizen-rule is in fact the oldest, purest form of democracy ever devised: sortition. To help us understand it—and its illustrious history—Sintomer takes us on a journey that starts 2,500 years ago.

II. The Life of Lots

Democracy dates to time immemorial, practiced by many hunter-gatherer bands and complex societies the world over for tens of thousands of years. But when it comes to the west, classical Greece makes for the most famous example, and the best understood. No Hellenic polis was more democratic than Athens, which implemented its system through a series of reforms and revolutions starting in 508 BCE. Their regime, perfected over nearly two centuries, has been treated extensively by scholars like Mogens Herman Hansen and Josiah Ober. Sintomer summarizes its sophisticated design and gives you an appreciation of its broad success.

Over a 30 year period, a quarter to a third of Athens’s citizens over 30 served for a year on the all-important Council of 500 or for a month on its executive board, thanks to selection by lot and mandatory rotation. Nearly 70% served at least once in their lifetime, and a still larger proportion were called upon to serve as a juror either on a legislative council or judicial tribunal. And since the presidency of the Council rotated every 24-hours, over time thousands of people could proudly proclaim, "I was president of Athens for a day!" In short, almost every citizen took a turn at governing at some point, in some way. That’s a level of participation unmatched by any regime in human history and led to the astonishing cultural efflorescence that shapes us to this day.2

It’s the life of sortition outside of Athens, though, that makes for one of the chief insights of Sintomer’s study. He explores its practice in religious contexts over the ages, noting its presence in the Bible and various shamanic cultures. While the Catholic Church banned it for selecting bishops, Protestants were able to rehabilitate sortition techniques in a number of reformed and Calvinist communities. The Romans used it for both religious and certain secular purposes, and it enjoyed widespread use in India and various indigenous tribes of South Asia for centuries down to the present.3

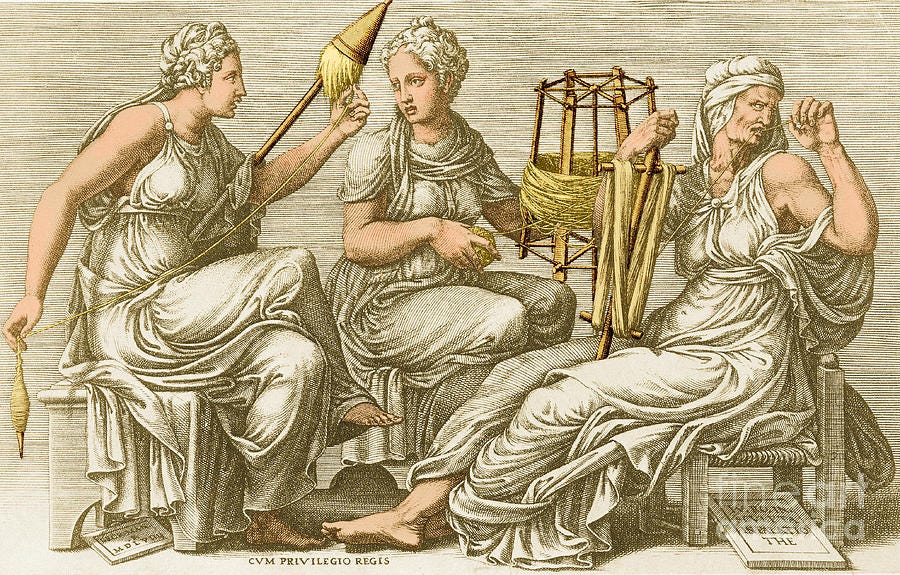

In Europe, sortition survived the classical age and continued into the Renaissance. It’s here that the book really begins to expand your mind. Sintomer offers a wealth of insight into the deployment of lotteries by the Italian communes, especially the republics of Venice and Florence. For 600 years, from 13th century to 1797, the former used a labyrinthian process of sortition and election to select its doge. “Venetians were convinced that they had the best electoral system in the world,” Sintomer says, “and no voice came to contradict them; in fact, most foreign observers agreed.” Florence also used a combination of lots and votes to apportion thousands of government posts over the centuries, from 1250 to 1530. The political systems of these and other Italian city-states contributed to the birth of a civic humanism that indirectly inspired the revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries.4

The Venetian and Florentine regimes, however, were not democracies—in their context, sortition was used to create “distributive aristocracies.” Only the elite were eligible for selection, though that included the rising bourgeoisie. This is an important lesson for today’s advocates of lotteries: while sortition itself is democratic, it can be put to anti-democratic purposes. Nevertheless, even with its limited use by the Italians, sortition sparked the development of modern republican theory by figures like Machiavelli.

As Sintomer says, democratic lotteries “reflected a consensus-based political order that was ideally oriented towards the common good, one where the plurality of interests was viewed negatively and internal conflicts were condemned.” Sortition, he continues, “helped the political community to transcend the divisions caused by factionalism, patronage, and corruption.”5 A brilliant quote from the Florentine intellectual Francesco Guicciardini (1483-1540) captures the vices of elections (which favor the rich) and the virtues of lotteries (which favor the common man):

Of course, selection by lot for public offices could also lead to conflict, but it would be more honest to tolerate a little disorder than to exclude the rest of us forever, as if we were enemies or people from another city, or as if we were donkeys interested only in fetching wine or drinking water…If we are as much citizens and council members as [the aristocrats] are, the fact that they have more possessions, more relatives, and more money does not make them citizens more than we are; if the issue is who is best suited to govern, we have the same mind, feelings, and tongue as they have, and perhaps fewer of the appetites and passions that corrupt people’s judgments.6

Beyond Italy, sortition was used by many other urban republics in the early modern period, including in Spain, England, France, Germany, and the Swiss cantons. In China, meanwhile, the imperial dynasties used lots to administer the most advanced state apparatus on earth at the time. After taking qualifying exams, civil servants were allotted their posts, which prevented graft and nepotism and purified the meritocracy. Across the Atlantic, there were several attempts to implement sortition in the English colonies of North America, especially Pennsylvania and New Jersey. While these were unsuccessful, the use of juries in criminal trials flourished, to the point today where millions of Americans are summoned annually and nearly 160,000 picked by lot to serve at the state or federal level.7

Far from being an exceptional procedure, then, for centuries democratic lotteries were considered a perfectly acceptable way to choose officials both in Europe and Asia. Even when combined with elections and co-optation, sortition made for an essential feature of republican regimes and was hailed as a balm for numerous pathologies. It served as an antidote to corruption and intrigue; limited the factionalism and power struggles of elites; softened the psychological blow of losing; and replaced crony clientelism with the ideal of a united community governed by the common good. Democracy by lottery wasn’t an aberration. On the contrary, it’s the lack of lotteries in our time that’s bizarre. Which prompts the question: why?

III. The Strange Death of the Democratic West

The standard narrative about how sortition disappeared from western political life, one that I’ve subscribed to myself, is quite simple: the revolutions in France and America in the late 18th century were led by landed gentry and bourgeois professionals. While they opposed hereditary kings and nobles, they in no way wished to give power to the people. They were anti-democrats. Instead, they wanted to implement a new order based on mixed regimes that would ensure that men like themselves would rule. And so they rejected lotteries and turned to elections.

Sintomer doesn’t deny that the liberal elites who helmed these events were oligarchs at heart. “What were created in Western Europe and North America were ‘elective aristocracies,’” he says, “arrangements where the core institutional power was largely monopolized by the elected few.” Elections benefitted “a relatively small group of people coming from a privileged social stratum,” he continues, “and they usually implemented policies that profited these same strata.”8 But, as he illuminates for us, there’s more to the story. By the 1770s, sortition’s radical purpose had been lost. The only living examples of its use were among the Swiss, where it continued to serve aristocratic ends. More importantly, things began to change in western political thought and its theory of republicanism.

About this time, liberalism entered the zeitgeist, thanks to an injection by John Locke (1632-1704). The Englishman was a philosopher of political consent, not self-rule. He justified elite domination by imagining a social contract between government and the governed, in which the body politic “consents” to surrender some of its liberty to the state to secure its safety. Likewise, the French philosophes Montesquieu (1689-1755 ) and Rousseau (1712-1778) desired an elective aristocracy, with the wisest citizens picked to serve. Sortition, to them, was anachronistic and dangerous, elevating potentially incompetent people to administer a vast bureaucracy. Meanwhile, in Germany, Hegel differentiated the peer judgment involved in the jury system from the general interest represented by the state, thereby denying juries a role in politics.9

These ideas led to three sea changes in the political imagination, which, together, killed democracy by lot:

“Identity” Representation vs. “Mandate” Representation. In classical and early modern republican theory—based on sortition—the operative notion was “identity” representation. Citizens chosen by lot were considered to be the community in microcosm; the part stood for the whole. The assembly, in this worldview, is the community. Citizens form a single legal person with their allotted representatives and are thus bound to the latter’s decisions. In the new worldview, though, citizens bequeath a legal right to agents to speak on their behalf and make decisions for them. The representative body is not a stand-in for society writ-large. Rather, it's received a mandate from the latter to rule in its stead. The ritual of election re-enacts the primordial moment of designating delegates.10

Meritocracy. The new republican theory placed virtue and talents in opposition to the hereditary privileges of the nobles. It praised wisdom, education, and devotion to the common good, but subordinated them under a plutocratic superstructure: At the time, the word capacity referred not just to education, but also the ability to pay tax, i.e., landed gentry. Thus, the virtues required to rule were (the liberal elite believed) unequally distributed among the populace. Moreover, they stressed the competence of an individual representative, rather than the intelligence of the entire body. Unlike in China, which saw sortition as perfecting its meritocracy, this new conception made any use of lotteries anathema.11

The Irrationality of Chance. Finally, a fundamental shift occurred in the attitude toward randomness: Instead of being understood as a rational solution to the pathologies of the polity, sortition came to be viewed as literally absurd. Back in 16th-century Florence, Guicciardini put the fundamental dilemma with politics thus:

The problems stem from the fact that there is a type of men who have been fortunate in the game of life, who have won the jackpot, and who think that the state belongs to them because they are richer, because they are more noble, or because they have inherited a formidable legacy from their parents and ancestors. And we who have lost out on the game of life, we’re not worthy of honors; we should content ourselves with lowly positions and continue to bear our cross as we have done before…In other words, they don’t remember that we are all citizens: they feel like they are worth more than others, they support each other when they are up for election, and only vote against…those who have not been so lucky in life.12

Democratic lottery, for him, was thus a logical mechanism that compensated for the vagaries of birth. But the ascendent liberals of the 18th century disagreed; they thought sortition seeded chaos into the system. Moreover, it denied citizens (they claimed) the ability to express “the general will” through rational choice, i.e., elections.13

As a result of these shifts, almost no one defended sortition during the Age of Revolutions. What radical democrats there were called for small self-governing communities led by town meetings, along with referenda and recall elections. Tom Paine suggested a lottery to select the Speaker of the House, and during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, James Wilson advocated that the Electoral College should use the Venetian procedure to select the President. But his idea was rejected by the delegates without discussion, and Paine by that point had been ostracized from their company.14 Subsequent generations of reformers, well into the 20th century, continued to agitate only for an expansion of rights and the franchise, not sortition. Even the socialist march of the late 1800s was suspicious of selection by lot. Avant-garde was their rallying cry. Sintomer sums up the situation aptly:

Squeezed between the growing professionalization of politics and the widespread popularity of elections, political sortition was largely relegated to the annals of history.15

IV. Democracy 3.0

This brings us full circle to where we began: modern political regimes, thanks to their plutocratic character, are now buckling under the twin scourges of neoliberalism and authoritarianism. Despite endless pronouncements to the contrary, the claim that capitalism supports democracy was only ideological and always ambiguous, Sintomer reminds us. In the second half of the twentieth century, the most democratic countries—those in which human rights and political equality are most fully realized—are those in which capitalism has been tamed by the de-commodification of the public sector. But where this balance has not been struck, inequality reigns and society is in free fall. “As a result, the political system has lost control of the situation,” he says. “Why should we be surprised that the energies awakened by the system are essentially negative?”16 The wages of sin, St. Paul says, is death.

It’s within this whirlwind that democracy by lottery has—suddenly, improbably— reappeared. Beginning with British Columbia in 2004, hundreds of citizens’ assemblies, convened by sortition, have occurred around the world in recent years. Sintomer narrates this history and summarizes how these assemblies achieve equality and render impartial decisions. Within this democratic wave, three fresh political imaginaries have emerged, built by different groups of contemporary sortition advocates. The first, made up mostly of academics, advocates for the use of lotteries to create limited experiments in deliberative democracy. The second, consisting of popular writers and activists, sees sortition as a fundamentally anti-partisan tool, freeing us from the conflicts of party politics. Finally, a new generation of radical democrats—many coming out of leftist and green parties—envisions lotteries as a tool for realizing an egalitarian society, especially in the modes of production and consumption.17

The success of this new demand for democracy by lottery will depend on whether these three imaginaries can unite their efforts. Likewise, its champions must overcome the challenges to sortition that emerged with the French Revolution, which Sintomer outlines as follows:

“Embodied” Representation and the Politics of Presence. Against the charge that sortition subverts the mandate theory of politics, its advocates must articulate a new kind of representation. Through the science of lotteries, citizens’ assemblies reproduce the community in microcosm—a body that, quite literally, looks like us. And through their deliberations, these “mini-publics” come to decisions that accurately reflect the public’s judgment, if everyone had the time, information, and chance to engage with their fellow citizens. With political parties hijacked by special interests, citizens’ assemblies carry greater legitimacy because of their symbolic representativeness: it’s not just the ideas they express, but the identities of the members expressing them—equitable numbers of workers, women, and marginalized groups. This lends much greater authority, responsiveness, and accountability to allotted bodies than elected ones.18

Epistemic Democracy and the Wisdom of Crowds. Against the charge that sortition is irrational and empowers incompetence, citizens’ assemblies illustrate how the cognitive diversity of a group of everyday people selected by lot achieves a much greater intelligence than panels of specialists or elected representatives. By aggregating the knowledge of experts and subjecting it to careful scrutiny and common sense, the collective reasoning of the group results in judicious policies and rewards long-term thinking, instead of the short-term illogic of politicians.19

The Politics of Peace. Von Clausewitz’s maxim that war is politics by other means implies the reverse: politics is war by other means. Today, that war has left citizens exhausted, disillusioned, and turning to actual violence. Democracy by lottery offers relief from the permanent campaign mode and agonistic quality of partisan power struggles. Far from consensus by the lowest common denominator, citizens' assemblies yield robust results. They surface and engage conflicts in a civil manner; air all points of view; articulate substantive agreement and real solutions; clarify choices; identify levels of support for various positions; and allow minority voices to feel heard and respected. Sortition, when applied well, restores the old republican ideal of a united community serving the common good, and reaps the fruits of a secure, prosperous, free society.20

The answer to our present calamities is clear: we need Democracy 3.0, a new regime where We the People, chosen by lottery, finally rule ourselves. This must be a hard reset of the system; there’s no time for tinkering. “Given the massive disrepute into which institutional politics has fallen,” Sintomer says, “preserving the status quo is neither realistic nor sufficient. A ‘real utopia’ is needed, and randomly selected assemblies and other mini-publics must be part of this new landscape.” Career politicians, however, will never accede to their loss of power, and mere “normative arguments exchanged in gentle conversation” will not convert them. “The changes to come are huge,” he writes, “and even revolutionary.” It’s time we all joined the fight.21

Sortition comes from the Latin word for fate. The ancients believed it was the destiny of those selected by lot to serve. Views of providence have changed: Vox populi, vox dei. Yet one thing’s clear: this new crusade for democracy will depend upon not just our efforts, but the blessing of the Almighty. In 1714, eight magistrates in Basel—who were also theologians—placed the fate of their republic in the hands of the God of chance:

The means that the good God has left us to pull a large part of the mud out of our unholy intrigues is the Lot…The Lot, who is not governed by any man, but by God alone. The Lot, who looks at no particular person, who does not cling to any party, who does not let himself be won over by flattery or promises, who is not frightened by the threats of the mighty…The Lot, who does not make anyone a slave to a party…This unpassionate Lot, who, alone, can help us.22

Amen.

Sintomer, The Government of Chance (2023), 31-32.

Sintomer, 53-54.

Sintomer, 44-45; 66-68.

Sintomer, 74-78; 84-89.

Sintomer, 122-123.

Sintomer, 86-87.

Sintomer, 136-150.

Sintomer, 19-20.

Sintomer, 131-135.

Sintomer, 72-73; 164-165.

Sintomer, 157-158.

Sintomer, 96.

Sintomer, 184-185

Sintomer, 162.

Sintomer, 182.

Sintomer, 25-28.

Sintomer, 237-249.

Sintomer, 254-259.

Sintomer, 260-265.

Sintomer, 265-267

Sintomer, 268-277.

Sintomer, 118-119.