The second episode of Lincoln’s Dilemma, “So You See, the Man Moves,” continues the distorted thesis of the first. It starts by reasserting that Lincoln didn’t want to end slavery at the outset of the war. It pushes this claim further, insisting that the conflict’s carnage caused him to suffer, which opened his heart to the humanity of enslaved people and drove him toward emancipation. The episode’s opening recounts in detail the death of his son, Willie, in February 1862. The film thus renders history in terms of psychology and emotion—the grief that assailed Lincoln, the theory goes, put him in touch with the humanity of the downtrodden, raising his eyes to abolition. Christopher Bonner says that the slaughter made Lincoln care about a “broader” set of Americans, meaning Black people (this is underscored, in case we didn’t get it, by visuals of the enslaved).

But the episode’s thesis collapses under the documentary’s own evidence. In Episode 1, the film relates how Lincoln always found slavery abhorrent—that the sight of enslaved people was, in his words, a continual torment to him. So by its own admission, then, the series accepts the fact that Lincoln’s “dilemma” over slavery was not about morality—it was about politics and law. He forever hated slavery, called it a monstrous injustice, and said he could never remember a time in his life when he did not so think and feel. Clearly, then, the issue was not about the man’s compassion.

There was something else, then, to explain why he didn’t unilaterally abolish slavery at the outset of the war. That little thing was called the Constitution. As I related in my previous post, Lincoln accepted the Federal consensus—the idea that the Constitution protected slavery where it already existed. But he and the Republicans, from 1854 onwards, crafted ways to bring about slavery’s demise through a combination of indirect measures. And when the war broke out, they immediately began emancipating slaves directly with the First Confiscation Act of August 1861.

Edna Greene Medford claims that Lincoln’s initial problem was that he was “wedded” to the Constitution and didn’t think you could “mess with property” because of the Fifth Amendment. This is buries the truth—Lincoln and the Republicans didn’t think enslaved people were property. As James Oakes relates in Freedom National, that was the crux of their entire dispute with the South. Slaveholders asserted that the enslaved were a category of property. Lincoln and the Republicans completely disagreed, pointing out that the Constitution nowhere protects such a thing as property “in man.” All references to enslaved people in the original Constitution refuse to call them “slaves”—the document refers to them instead as “persons held to service.”1

This may seem like semantics to us, but it made for a crucial point of law. It was an admission, the Republicans argued, that the Founders didn’t consider enslaved people to be property—they were persons. The Republicans cited figures like Madison, who, as Sean Wilentz writes in The New York Times, took pains during the constitutional convention to deny the idea of property in man. Even though the Constitution made compromises over slavery in a few places, it never endorsed the principle of human slavery. That’s one reason why, as soon as war broke out in April 1861, Lincoln and the Republicans justified emancipating enslaved people—they were not private property under the Constitution. And when the southern states left that Union to make war on the United States, they forfeit whatever protections for slavery the Constitution did afford. This was especially so since the Confederates were using enslaved people to wage war.2

As for being “wedded” to the Constitution, Harvard Law professor Noah Feldman argues the opposite in a new book, The Broken Constitution: Lincoln, Slavery, and the Refounding of America. He claims that Lincoln, far from slavishly obeying our founding charter, remade it in unprecedented ways. As he relates in an opinion piece for The New York Times, Lincoln did three things that broke constitutional law: He waged war against secessionists (something his predecessor, James Buchanan, didn’t believe within the power of the Federal government). He suspended habeas corpus in several places in the North (because of secessionist insurrections). And he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order without antecedent in U.S. history.

Who’s right—Medford or Feldman? I think the answer lies between them. Oakes is probably most accurate when he says that Lincoln and the Republicans strove for fidelity to the Constitution. But they believed that the war gave them powers that were extra-constitutional—they could emancipate slaves directly under the pretext of military necessity. While they could not say outright that abolition was the war’s purpose (that would be unconstitutional) they all knew that slavery was the war’s cause and that emancipation would be its ultimate effect.3

The episode continues with its misleading narrative. It reasserts the claim, hinted at in Episode 1, that enslaved people liberated themselves before Congress or Lincoln imagined emancipation. As I related in my previous post, this is inaccurate. In Freedom National, Oakes explains that the Republicans came into office in 1861 with a pre-meditated plan to emancipate slaves of disloyal states. The enslaved people who ran to Union lines did so because they’d heard that the Lincoln administration was on their side, for the first time in American history. The series dramatizes this through the incredible story of Robert Smalls, an enslaved man in Charleston who commandeered a ship and steered it toward a Union ship (he later served as an elected official in South Carolina and the U.S. Congress). We need to learn and trumpet such astonishing tales. But such self-emancipations were rare—a fact I’ll come to in the next episode. And even when they occurred, the people doing it were given the impetus by the new, antislavery Federal government.

The episode introduces Lincoln’s plan for getting the Border States to abolish slavery. These were the four slave states—Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware—that remained in the Union. The idea was to offer them material incentives to abolish slavery—state laws implementing gradual emancipation (as it had happened in northern states), with the Federal government offering monetary compensation for owners. A plan for voluntary resettlement of former slaves abroad was the final carrot.

Today, colonization strikes us as Lincoln’s most embarrassing belief. The film adopts a suspicious attitude toward the policy. “The message,” says the narrator, “was, ‘You should be free, but not here.’” Whatever our feelings now, colonization was a mainstream part of antislavery politics at the time. Lincoln inherited the idea from Thomas Jefferson and Henry Clay, two of his political inspirations. It was controversial within Republican circles, but Foner emphasizes its centrality:

Before the Civil War, no one, except perhaps John Brown, could conceive of a way to end slavery without the consent of slaveowners; there was simply no constitutional way that this could be accomplished. And it seemed impossible that whites would ever consent to emancipation unless coupled with the removal of the black population…For many white Americans, including Lincoln, colonization was part of a plan for ending slavery that represented a middle ground between abolitionist radicalism and the prospect of the United States existing forever half-slave and half-free.4

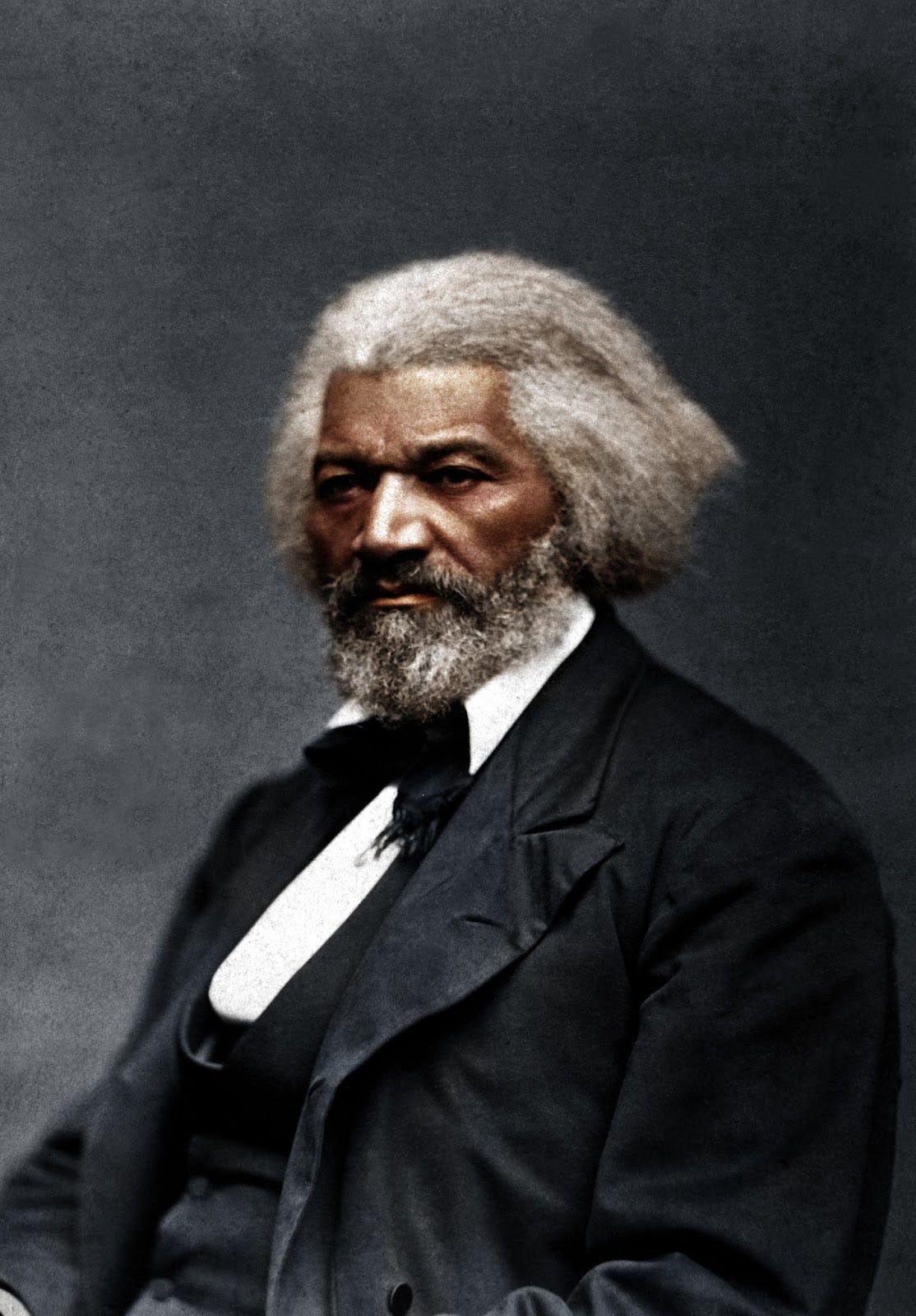

The vast majority of Blacks opposed the idea. But not all. African Americans in favor of separating included Martin Delany, the founder of Black Nationalism, and (for a time) the sons of Douglass. Their ranks grew during the 1850s.5 As for Lincoln, he never sought to make colonization mandatory (as some advisers wanted him to). Rather, he endorsed an optional plan mostly as an incentive to get slave owners to agree to emancipation. Instead of hoping and praying that their hearts would convert, he wanted to offer a substantive policy—the first in American history—to push slaveholders toward abolition. He was changing their material self-interest, an approach both pragmatic and progressive. He was altering the government from being actively pro-slavery (as it had been under all previous administrations) to explicitly antislavery.

The film also doesn’t mention Lincoln's other reason for endorsing resettlement: his fear that white hatred of Blacks was so great that they wouldn’t allow African Americans to enjoy equality in the United States. This was a pessimistic view, which Douglass disagreed with—he believed all people, born in America or emigrants to it, were entitled to the rights of citizenship. But given the violence visited on Blacks during Reconstruction, and a century of Jim Crow, maybe Lincoln was more realistic than pessimistic. In any case, he abandoned the colonization scheme when he issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, and unequivocally endorsed Black citizenship.

Douglass evolved, too—he came to endorse a kind of colonization by 1871. During the administration of Ulysses Grant, the President sought to annex the island of Santo Domingo and make it a U.S. state. He envisioned (along with taking the island’s economic resources) turning it into a haven for Black Americans. It would make for a safe place where—if they chose—African Americans could join the local Dominican community, enjoy the rights of citizenship, and find protection from white violence. He had Douglass join a commission and venture to the island to investigate the plan’s viability. The Black leader came back bearing a favorable report. The native population desired annexation, he claimed, as a way of securing freedom from slave societies like Spanish Cuba. Despite the imperialism of the idea (which drove Senator Charles Sumner apoplectic), Douglass made many speeches praising the policy. He saw the United States—with slavery destroyed and Black people made citizens—as having a destiny to bring freedom and “civilization” to people living in underdeveloped lands. Lincoln’s Dilemma, conveniently, leaves all this out.6

Returning to Lincoln, scholar Kellie Carter Jackson states that he didn’t view Blacks as citizens in 1862. Bryan Stevenson goes further, saying that the President “didn’t share the aspirations” of Black people. This is disingenuous and debatable. As I relate in my first post, during his 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln confessed that he didn't think Blacks were the social or political equals of whites. But he made this admission reluctantly, under attack from his racist rival, and with embarrassment—he never trumpeted it. Moreover, he had to do so in order to get elected—most white Northerners, even if they opposed slavery, didn’t believe Blacks should enjoy political equality. To call for complete social and political parity out loud in 1858 was to touch the third rail of politics—it would have cost Lincoln votes to Douglas, who wanted slavery to spread further.

But, as I also pointed out, Lincoln believed Blacks were the equals of whites under natural law, as expressed by the Declaration of Independence. He thought they had the right to freedom, to the fruits of their labor, and to family life. As Michael Burlingame relates, Lincoln was a racial egalitarian at heart. He sympathized with enslaved people, wanted them to enjoy their natural and economic rights, and have the opportunity to advance in the “race of life,” as he put it—just as he had. He saw in the aspirations of Blacks a reflection of his own ambitions. He returned to this basic equality over and over in his debate with Douglas:

Let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the other man—this race and that race and the other race being inferior, and therefore they must be placed in an inferior position, discarding our standard that we have left us. Let us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout this land, until we shall once more stand up declaring that all men are created equal.7

What to make of these distinctions? Scholars disagree. Foner argues that for most of his life Lincoln struggled, like many whites, to imagine a biracial nation. According to him, Lincoln saw Blacks as having been stolen from their native land and thus should be allowed to return (oblivious to the fact that, by 1860, the vast majority of African Americans were born in the United States). Only after he witnessed the service of Black soldiers during the war did he evolve.

Wilentz, on the other hand, argues the opposite: that Lincoln recognized Black citizenship as early as the 1850s. Oakes agrees, relating how Lincoln quietly hinted at Black citizenship even as he denied it to Douglas. His statements in the 1850s were “hesitant and inconsistent,” Oakes says, but he was moving toward a solid pro-citizenship position. During his first inaugural address, in fact, he offered the South a compromise: I will have the Federal government enforce the Fugtive Slave Act if you will agree to revise the law to accord Blacks Federal recognition of the “privileges and immunities” of citizenship.

A year and a half later, in August 1862— before Lincoln even issued the Emancipation Proclamation—Attorney General Edward Bates produced a thirty-page document stating that, as far as citizenship was concerned, the Constitution made no distinction between Blacks and whites. All were citizens—including Blacks born and raised as slaves on American soil. As soon as they were emancipated, they were entitled to all the protections of citizens under the Constitution. This brief went directly against the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott case of 1857. Moreover, it was the first time that the Federal government crafted a national standard of citizenship—before that, it was a matter left to individual states. This document, issued at Lincoln’s behest, laid the legal groundwork for the 14th Amendment in 1868: all people born in the United States are full citizens.8

The documentary points out that Lincoln’s plan for the Border States failed (they didn’t accept the policy), which prompted him to rethink his approach and decide to go for full-blown emancipation by military decree. This is a bit confused. The plan for the Border States, as Oakes explains, and the one for military emancipation were separate and distinct. The first was a peacetime policy for the abolition of state laws creating slavery. The second was a wartime policy for emancipating individual men and women directly by the Federal government, while leaving the laws on the books. Yes, the Border State plan was defeated. But that wasn’t what prompted Lincoln to choose the Emancipation Proclamation as his tool.

Rather, it contributed to his later decision to endorse an amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery everywhere. Most Americans at the time didn’t imagine amending the Constitution to solve national issues. The document had been altered only twice in the seventy years since the Bill of Rights. Citizenship and identity, for most Americans, was tied to their state, not the nation. The Federal government was extremely tiny in 1860, with just a few thousand employees, most working for the Post Office. So the change in Lincoln was not one of the heart, but of policy—as Foner says in the series, Lincoln’s greatness was his capacity for growth in ideas. He was always pointed towards Zion (as he said of the Radicals)—he just altered his thinking about how to get there.

The episode recounts how the Republicans in Congress abolished slavery directly in the District of Columbia in April 1862, with Lincoln signing it into law on the 16th of that month. It fails to mention all the other antislavery legislation they passed. That same month, on the 24th, the Senate approved a treaty with Britain that would allow the British to search American ships suspected of trafficking slaves across the Atlantic. (The show does relate, fascinatingly, the little-known story of how Lincoln endorsed the execution of Captain Nathaniel Gordon—the only American ever convicted of illegal slave trading). Congress also outlawed slavery in all Federal territories in June, thereby settling the main antebellum conflict. In addition, it welcomed West Virginia as a state after it broke away from Virginia, on the condition that its state constitution abolish slavery. Lincoln promptly signed all these bills into law—not the actions of a reluctant abolitionist. He and his fellow Republicans made good on their campaign pledge to create a cordon of freedom around the slave South.9

But the film continues its cautious portrayal of the man. It recounts the episodes in early 1862 in which Lincoln overruled Generals John C. Fremont and David Hunter. These generals had taken it upon themselves to issue emancipation decrees for all enslaved people in Missouri (where Fremont exercised jurisdiction) and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (where Hunter held sway). The film states that Lincoln rescinded their orders and leaves it at that. What goes unsaid is the reason he did so. It’s not that he disagreed with their antislavery views, or denied that the government could issue such orders in time of war. As I have shown, Lincoln and the Republicans were already emancipating slaves under the First Confiscation Act. They shared the abolitionist intentions of Hunter and Fremont.

Their objection had more to do with the chain of command—the generals had usurped their authority, issuing orders that went beyond the scope of Congress’s law. The First Confiscation Act liberated enslaved people who came into Union lines, but the commands of Fremont and Hunter went farther—they freed every slave in their jurisdiction, wherever they were. Lincoln simply wanted his commanders to follow the laws as Congress wrote them. Hunter issued his order on May 9, 1862. The President immediately rescinded it, preserving political authority in the hands of civilians—not the military. But he hinted that he was ready to make such a decision himself.10

In fact, he knew something Hunter did not—the Republicans were closing in on full-blown emancipation. Just two months later, on July 17, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act. This statute freed the enslaved people of all rebels in seceded states, pending a proclamation by the President. On July 13—while the bill was still being debated—Lincoln told William Seward, his Secretary of State, that he was prepared to issue the Proclamation upon signing the law. When he announced this to the rest of his cabinet on July 21, they—though stunned—agreed. Some made minor objections—to the scope of the decree, the military rationale, the way it would be implemented, etc. Most of these Lincoln dismissed. But Seward made a point he thought prudent: that the administration should wait for a prominent Union win on the battlefield. This would make the Proclamation come from a position of moral strength, rather than look like an act of desperation. Because such a victory didn’t occur until September with the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln delayed the decree by two months.11

The documentary does a decent job of providing context for Lincoln as he sat on the Proclamation. It describes him as a tight-rope walker trying to navigate between the conservative and radical factions of his party. This is fair. It explains why he issued contradictory statements (like the famous letter to Horace Greeley, editor of The New York Herald & Tribune) in which he said that his primary purpose was to preserve the Union, not emancipate slaves. As Wilentz points out, you have to understand what’s going on around Lincoln’s statements. He was priming the country for a Proclamation he’d already decided to issue. The show fails, however, to explain his poor meeting in the White House with Black leaders on August 14. Bonner recounts Lincoln’s haughty treatment of the delegation, in which he blamed Blacks for the war, pushed colonization, and said the races could never coexist.

What Bonner leaves out is that Lincoln met with many Black leaders, the first President to do so (and one of the only until Lyndon Johnson in 1964). Most of these meetings went well. The filmmakers thus leave in Lincoln’s worst day on the job, without highlighting his best ones. All other Blacks who met him spoke of the courtesy, respect, and dignity with which he treated them. What went wrong this day? Oakes explains how Lincoln’s behavior in this instance (while undiplomatic, even demagogic) was coached in subtle political meaning—he was trying to cover his political right flank from attacks by conservative Republicans and the Democrats. While not excusing Lincoln, Oakes mitigates his actions.12 “With his left hand, Lincoln leaked a conservative message of races not co-existing, so as to relax the majority of whites” says Ted Widmer in the episode. “But with the right hand, he’s moving radically toward extreme emancipation.”

Jelani Cobb claims that all this makes Lincoln an enigma. There’s some truth to that. He never kept a diary and was killed before he could write his memoirs. We don’t have access to his inner life the way we do others. Yet let’s not take this description too far—through his actions and speeches, we have a good overall sense of Lincoln’s political positions. Those are clear. From 1854 on, he evinced firm opposition to slavery, moving inexorably to deal it a death blow. Between the outbreak of war in April 1861 and his announcement to Seward that he intended to issue the Proclamation, fourteen months passed. During that interval, he and Congress passed numerous pieces of antislavery legislation.

Measured in terms of the life of an enslaved person, that’s fourteen months too long. But measured in terms of a politician—hemmed in by factions on all sides, not to mention the Constitution—that’s remarkably swift. No one could have predicted in 1861 that, just fourteen months later, Lincoln and the Republicans would destroy slavery head on. Why not underscore this revolution, instead of giving it short shift? The filmmakers, like the creators of The 1619 Project, may argue in reply that they want deconstruct a saintly view of Lincoln by emphasizing his warts. But as Wilentz writes, “Whether or not the public still regards Lincoln as a saint, a myth cannot be corrected by a distorted view.”

James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), 8-14.

Oakes, 8-14.

Oakes, 113-118.

Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York W. W. Norton & Company, 2010. Kindle Edition.), 125-127.

Foner, 128-129.

David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 536-545.

Lincoln-Douglas, 5th Debate: https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/debate5.htm

Oakes, 353-360.

Oakes, 261-276.

Oakes, 213-218.

Oakes, 302-307.

Oakes, 307-313.