The Cross & Salvation

On Atonement Theology

A note for my readers: Despite my best intentions, this post became long and academic in places. I’ve broken it up into sections and sub-sections, with images, music, podcasts, and videos to try to aid your reading. But I encourage you to take it chunks. Luckily, the Easter season is fifty days—you’ve got plenty of time.

I.

I didn’t post last week while my wife and I observed Holy Week, which the Orthodox Church is keeping right now. Palm Sunday found us in Wilmington, NC (we were there for a week with my extended family) where we attended liturgy at the oldest Episcopal parish in the city, St. James. Back in Boston, I prayed with a good friend at a Tenebrae service in a Cambridge monastery on Wednesday, before celebrating the Triduum at St. Paul parish in Brookline. This culminated in a cold sunrise service on Easter Sunday at a park overlooking Boston, featuring some of the greatest hits of the St. Louis Jesuits.

Like my politics, my theological views are idiosyncratic. By that, I mean they don’t always scan cleanly along the left-right divide. This leads to conflicts both with conservatives (who don’t get my socialist economics) and liberals (who balk at my orthodox christology). Few positions, however, land me in more debates than my views on the crucifixion—the death of Jesus.

This sub-field is known as ‘soteriology,’ or theology of salvation. It explores the meaning, implications, and dynamics of the cross. For centuries, Chrisitans have professed—in prayer and worship—that the cross “saves” us. What do we mean by this claim? How does the cross do this and why? What exactly happened on Good Friday? Soteriology aspires to answer these questions, in fidelity to the revelation of scripture, the liturgy of the church, and the witness of the People of God.

Unlike with christology, however, the church has never pronounced a definitive doctrine of salvation. There’s no conciliar formula that encapsulates what Christians believe about the crucifixion, which speaks to the reality that at a fundamental level, it defies reason. The cross baffles us to this day—a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, Paul of Tarsus writes (1 Cor 1:23).

This has led some to conclude that there’s no normative vision of soteriology at all—that it’s up for grabs and open to any and all interpretations. Such an impulse, though, is misplaced. Despite a lack of credal concision, the tradition has, over the centuries, articulated a coherent theology of the cross that roots itself in scripture.

II.

But where to find it? Many Christians don’t have the time or training to wade through thick tomes and make sense of the evidence. I was lucky in graduate school to take a course that devoted an entire semester to the topic, but that’s rare. Fortunately, a book appeared a few years ago that changed the game. In 2015, Fleming Rutledge published The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ through Eerdmans press.

Rutledge is an Episcopal priest known for her dynamic sermons and profound reflections on scripture. She combines the training of a systematician with a style fit for a popular audience. The Crucifixion garnered praise across the ecclesial spectrum. Catholic bishop Robert Barron called it one of the most “stimulating and thought-provoking” books of theology he’d read in a decade. Stanley Hauerwas, perhaps the greatest American theologian of our day, dubbed it the “work of a lifetime.” Having read it recently, I agree.

In prose that packs a punch, Rutledge treats the major aspects of the topic—the gravity of sin, the godlessness of the cross, and the question of justice. The crucifixion is primary to the Christian faith, she insists, though liberals seek to downplay it and conservatives to weaponize it. “Christianity is the only major religion to have as its central focus the suffering and degradation of its God,” she quotes from a 1981 PBS documentary. In the earliest texts of the New Testament, Paul says he preaches nothing “except Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor. 2:2).

When it comes to the Gospels, the long, dramatic passion narratives are the oldest parts of the stories, comprising one-fourth to one-third of their total length. As Rutledge says, scripture presents Jesus’ crucifixion—validated by his resurrection—as the defining feature of his life and ministry. All his work, however important, was provisional until then. The cross seals his mission—it illuminates and explains everything that preceded it. She renders the point as follows:

The crucifixion is the touchstone of Christian authenticity, the unique feature by which everything else, including the resurrection, is given its true significance.

After exploring the biblical texts and the tradition, she admits that there’s no single, explicit theology of salvation. At the same time, though, she identifies eight motifs that provide a constellation of meaning. These are:

The Passover and Exodus

The Blood Sacrifice

Ransom and Redemption

The Great Assize (Judgment)

The Apocalyptic War: Christus Victor

The Descent into Hell

The Substitution

Recapitulation

While they appear contradictory, these ideas reveal an underlying consistency. A “unitary reality” pervades the different accounts of the crucifixion, she says, and the multiplicity of motifs “attests to the same truth.” Taken together, they produce two overarching categories—they point to two things happening on the cross of Christ:

God’s definitive action in making vicarious atonement for sin: the cross is understood as sacrifice, sin offering, guilt offering, expiation, and substitution. Related motifs are the scapegoat, the Lamb of God, and the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53.

God’s decisive victory over the alien powers of Sin, Death, and the Law: the cross is understood as victory over the Powers and deliverance from bondage, slavery, and oppression. Related themes are the new exodus, the harrowing of hell, and Christus Victor. This category is linked to the Kingdom of God and is thus strongly oriented toward the future—it has an eschatological thrust.

The motifs reveal, reinforce, and play off each other, functioning in a dynamic symbiosis. We can’t isolate one as the sole explanatory idea or erase those we don’t like. When we do, things fall out of balance and we produce a theology that ignores critical content. We’re not free to make up Christianity as we please. If we abolish radical ideas to make the Gospel fashionable, palatable, or politically correct, we fail to proclaim the kerygma—the Good News of Jesus. We trade salvific revelation for facile fads; grace that’s costly for grace that’s cheap. Nowhere is this more true than when it comes to the cross.

III.

I could write a post about each of these motifs, but I thought today I’d focus on one that makes contemporary Western Christians the most uncomfortable: substitution. Even more so, ‘penal substitutionary atonement’. Translated into English, it means this: Jesus, on the cross, suffers the divine punishment for sin in our place, thereby making amends for our injury and restoring humanity to full communion with God. That may sound obvious—isn’t it basic to the Christian faith? Even non-believers could tell you that Christians think Jesus died “for their sins.”

Yet throw this phrase around the halls of divinity schools, and you’re apt to get looks of shock and be treated as a pariah. Many liberal theologians, pastors, and preachers tip-toe around substitution, either ignoring it or recasting its troubling implications. Enter a progressive church today—whether Catholic, Anglican, or Reformed—and chances are you’ll hear nothing about bread-and-butter themes like sin, redemption, and the suffering of Christ. During a Good Friday liturgy a few years ago, I even heard a cleric explicitly deny—from the pulpit—that Jesus atoned for sin. Rutledge sums up the hostility to substitution well:

It is not an exaggeration to say that in some circles there has been something resembling a campaign of intimidation, so that those who cherish the idea that Jesus offered himself in our place have been made to feel that they are neo-Crusaders, prone to violence, oppressors of women, and enablers of child abuse.1

I understand. Substitution used to upset me, too, prompting revulsion, horror, and disgust. More than any other idea, it dredges up childhood trauma—psychological wounds stemming from fear of discipline, corporal correction, and angry adults. It seems to render Christianity sado-masochistic: a twisted religion predicated on a cruel, vindictive Father executing his innocent Son to satisfy his blood-lust.

Certainly it’s been presented this way at times, both in theology and in the popular imagination. Many evangelicals and Catholics flocked to Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ back in 2004—an odious, anti-semitic, even anti-Christian film. Rather than reveal the heart of the cross (which is self-gift), Gibson drenched his picture in pornographic torture that betrays the Gospels. The evangelists pass over the violence of the passion with barely a word—Gibson shoves your face in gore.

But those same scriptures attest to the fact that Jesus does suffer vicariously for humanity’s sin, and that this is the divine plan behind his incarnation. Rather than an accident or unintended consequence of his righteous life, the cross was the express purpose for his advent. In each Gospel, he predicts his passion and resurrection three times. In the Garden of Gethsemane, he willingly submits to undergo the cross in our stead so that we may be rescued.

The bulk of the theological tradition—from Athanasius to Augustine, Anselm to Aquinas, Luther to Calvin, Barth to Von Balthasar—underscore the centrality of substitution. I wrestled fiercely with this motif in my course, but ultimately came not only to accept it, but to appreciate and even celebrate its beauty.

IV.

Let’s take apart the motif piece by piece, in reverse order.

Atonement. Critics of atonement theology argue that it was an invention of Anselm of Canterbury in the Middle Ages that wasn’t present in the scriptures or the early church. But the record indicates otherwise. The word stems from Middle English and simply means “to reconcile or bring into harmony and unity.” Theologian Lisa Sowle Cahill expands on it as follows:

In a Christian theological context [atonement] refers to the creation of a mutual relationship of love between God and humanity. Insofar as a prior state of alienation is presumed, atonement is also "reconciliation."2

In this vein of thinking, sin was an ontological wound to the order of creation. It breaks humanity’s relationship with the Creator, throwing us into exile from God’s presence. The Bible is the story of God’s rescue mission for this lost creation, which took its penultimate step when the Word of God entered into creation as the incarnate Son. Through his nativity, Jesus brought the divine presence into human nature and then into “every dark, lonely, and tormented corner of existence,” as Cahill says, employing the ‘medicinal analogy’ of Athanasius from the fourth century. This mission found its culmination on the cross, where Christ made himself a sacrifice that bridges the “unbridgeable distance” between humanity and God, as Salvadoran Jesuit Jon Sobrino says.

The biblical ideas of ‘sin and atonement,’ ‘exile and return,’ ‘alienation and communion,’ ‘rejection and reconciliation,’ all share a similar meaning when it comes to atonement and the cross. As Rutledge relates, the Romans had two main forms of execution. Beheading was imposed on citizens, considered a quick, humane sentence. Crucifixion, on the other hand, was reserved for slaves, criminals, and the dregs of humanity. A long, agonizing, public execution, it was intended to degrade the victim, rob him of his dignity, and condemn him to the “death of a beast.” For Jews, meanwhile, to be hanged on a tree was a sign that you were cursed by God.

By going to the cross, then, Jesus brought the divine life to the place of humanity’s total exile from God. Rutledge puts it thus:

God in Christ on the cross has become one with those who are despised and outcast in the world. No other method of execution that the world has ever known could have established this so conclusively.

The cross, then, is not about physical pain—it’s about humiliation, shame, and rejection. Again, the Bible doesn’t highlight the violence of the passion at all. Rather, it points us toward the spiritual suffering of the Messiah, Jesus’ cry of abandonment—“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The resurrection, then, is about restoration, reconciliation, and return.

With Easter, God ironically turns the cross of Christ into our way to the divine presence. His death and resurrection undid the alienation of sin, yielding communion. In the shedding of his blood, Jesus ‘re-members’ us—he puts us and our relationship with God back together. He brings us home, makes us one. Paul speaks of this in terms of our “adoption” by God, in which we share in the divine life of the Trinity.

Substitution. Some liberals get on board with atonement when you describe it in way I just did. They falter, though, when we come to ‘substitution’—the idea that Christ achieves this atonement by suffering on our behalf. In addition to its classist elitism, this distaste derives from “at least in part from the contemporary wish to avoid the themes of sin and judgment,” Rutledge states, “a move that is typical of the atmosphere in the culture and the churches today.” Again, critics get around this uncomfortable theme by asserting that substitution isn’t found in the Bible or the ancient church, but was conjured in the 16th century by Reformed theologians like Calvin.

Once more, Rutledge debunks this claim. The New Testament repeatedly uses the Greek prepositions huper and peri when describing the crucifixion, translated as “Jesus Christ died for our sins.” Sometimes these words mean “for our sake,” sometimes “for our benefit,” and sometimes “in our place.” This last phrase, especially, connotes the idea of ‘representation’ or ‘substitution.’ For scriptural support, she elaborates on Romans 8:3-4; Galatians 3:10-14; 2 Corinthians 5:21; 1 Peter 3:18; and, of course, Isaiah 53.

When it comes to the passion narratives, Luke’s Gospel emphasizes the fact that Jesus is exchanged for Barabbas, the crowd choosing to crucify Christ instead of a murderer and insurrectionist. Jesus literally takes the place of the guilty, and Luke wants us all to see ourselves in Barabbas. In fact, we are to see ourselves as the ones who crucify Jesus, like the crowd. Rutledge sums up the insight of all these passages:

Do they not contain the idea—among other ideas—that the sarx of the Savior, in which sin was condemned, was a substitute for our sarx—his exchanged for ours? And if he was condemned in the flesh as the representative man of sin, whose place was he taking? Whose but all humanity’s?3

She goes on to demonstrate that the Patristic scholars of the ancient church—thinkers like Athanasius, Cyril of Alexandria, and John Chrysostom—all contain the substitution motif in their works. It’s not the focus of their soteriology (they highlight the Christus Victor idea much more) but substitution lies in the background. Rather than inventing it out of thin air, then, Luther and Calvin merely brought it to the foreground.

Penal. This is last redoubt of liberals. You may get them to assent to atonement, maybe even substitution, but the idea of Christ suffering a penalty is positively anathema—especially understood as a divine penalty. They might accept the idea of the cross as a punishment inflicted on Jesus by his executioners—the Roman and Jewish authorities. But from God? Never. Rutledge attributes this aversion to a culture that abhors the notion of a punitive deity:

The whole idea of punishment evokes an image of a wrathful nineteenth-century father rolling up his sleeves and reaching for the rod. The archetype of the angry father is permanently and frighteningly lodged in the human psyche and cannot be displaced in this life…It would be a mistake, however, to construe the theological concept of punishment solely according to this wrathful image.4

As she argues, to reject the idea of a divine penalty for sin is to abolish the idea of justice—and even God himself. The Old Testament ascribes many traits to Yahweh, but the major one is righteousness—God brings justice to the poor and lowly. Not vague or amorphous, Yahweh’s justice is specific and particular, she says, “showing that God is attentive to the material details of human need.” The apocalyptic and prophetic books look forward to the “Day of Judgment” or “Day of the Lord,” when all injustice will be rectified. “A major theme of the messianic passages in the Old Testament,” she says, “is the coming of God’s kingdom of perfect justice.”

The Gospels take up this theme in its presentation of the Messiah. For instance, Mary’s Magnificat, her long prayer during her pregnancy with Jesus, proclaims that her son will bring justice to those at the bottom of society. This justice is portrayed as a dramatic reversal of the social order, as when the Lord threw down Pharaoh and liberated the Hebrews from slavery in Exodus. Later in Luke, Jesus reads Isaiah in his synagogue and announces that he’s come to fulfill its prophecy of good news for the poor and freedom for the oppressed.

Since God is holy, righteous, and just, then, the Lord must inherently oppose and condemn every form of sin, injustice, and evil. “Because justice is such a central part of God’s nature,” Rutledge says, “he has declared enmity against every form of injustice. His wrath will come upon those who exploited the poor and weak; he will not permit his purpose to be subverted.” She goes on:

God’s righteousness leads him to all lengths to oppose what will destroy what he loves, and that means declaring enmity against everything that resists his redemptive purpose. This is the aggressive principle in God’s justice.5

By committing sin, therefore, humanity has become complicit in evil and fallen under God’s judgment. According to the demands of justice, humanity must pay the penalty for sin. God cannot overturn the principles of justice and rationality without contradicting his own being.

But on the other hand, God doesn’t want to see humanity destroyed. For one, it would reflect weakness on his part—evil and suffering call into question God’s power and goodness. Moreover, God loves his creation. Humanity’s suffering—especially that of the innocent and poor—pains him. In fact, injustice toward the poor is one of the prime causes of his anger. As angry as he is, though, his love is greater. Both God’s anger and love express his complete involvement in and care for creation—they reflect his mercy.

God solves the dilemma by an action no one could anticipate: exchanging places with us and taking upon himself, in the form of the Son, his own penalty. Here, the Isaiah 53 passage becomes most relevant:

But he was wounded for our transgressions,

crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the punishment that made us whole,

and by his bruises we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray;

we have all turned to our own way,

and the Lord has laid on him

the iniquity of us all.Rutledge takes this passage and runs with it:

In the crucifixion and its vindication in the resurrection, we see how every Power that wars against God has been and will be overcome and ultimately annihilated. In this sense, we may say that Jesus Christ absorbs into himself the divine sentence against Sin and Death. When Paul says “God made him to be sin,” he can be understood to say that in the tormented, crucified body of the Son, the entire universe of Sin and every kind of evil are concentrated and judged—not just forgiven, but definitely, finally, and permanently judged and separated from God and his creation.

Rutledge acknowledges that the idea of punishment has been overemphasized and warped for dangerous purposes by some preachers and theologians over the centuries. But she cites none other than Karl Barth, the greatest Protestant theologian of the 20th century, for support. In his towering Church Dogmatics, he construes the idea of penal substitution thus:

If Jesus Christ has followed our way as sinners to the end to which it leads, in outer darkness, then we can say with [Isaiah 53] that He has suffered this punishment of ours. But we must not make this the main theme.

He follows up with a fine-print explanation:

The very heart of the atonement is the overcoming of sin: sin in its character as the rebellion of man against God, and in its character as the ground of man’s hopeless destiny in death. It was to fulfill this judgment on sin that the Son of God as man took our place as sinners. He fulfills it as man in our place, by treading the way of sinners to its bitter end, in destruction, in the limitless anguish of separation from God…We can say indeed that He fulfills this judgment by suffering the punishment which we have all brought ourselves.6

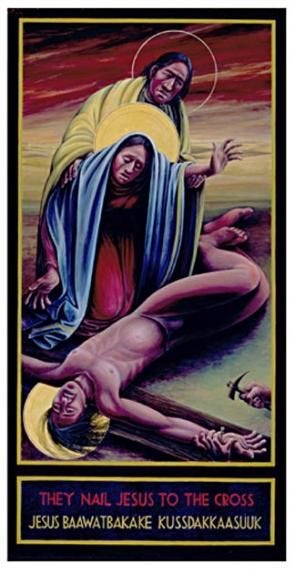

(Above, the Boston Liturgical Dance Ensemble performs a piece choreographed by Bob VerEecke, SJ)

V.

This exposition of the substitution motif sparks a slew of questions, complaints, and objections. Rutledge lists many of them:

It’s crude.

It’s culturally conditioned.

It views death as detached from the resurrection.

It’s incoherent: an innocent person can’t take on the guilt of another.

It glorifies suffering and encourages masochistic behavior.

It’s too theoretical, scholastic, and abstract.

It depicts God as vindictive.

It’s essentially violent.

It’s morally objectionable.

It doesn’t develop Christian character.

It’s too individualistic.

It emphasizes punishment.

While she rebuts all of these, she grants that the motif can fall victim to the abuses that these objections point out. Too often, especially in evangelical circles, it leads to an individualistic view of salvation (Christ saves me). While Jesus does save us, of course, as individuals, the New Testament emphasizes much more the idea that God saves us as a people.

Likewise, Reformed theology did damage the motif in the past by turning it into an abstract, schematic, forensic equation rather than the poetic idea as it’s found in the Bible. And with substitution, it’s all too easy to split off the death of Christ from the incarnation and resurrection. We must hold all three together in our soteriology. They form a play in three acts, with the crucifixion as the climax.

I want to address three other critiques, however, that I find important:

Substitution separates the Father and the Son. First, the idea of penal substitution can easily lead to separating the Father and the Son in our minds. Comedian Bill Maher, in one of his cynical assaults, put this charge well: “Christians believe God sent his son, Jesus, to earth on a suicide mission.” I catch his drift. In the wrong hands, the motif implies that an unhinged Father punishes his innocent Son to displace his pent-up rage.

Obviously, that’s not how to think about it. Rather, the passion is a joint project of the entire Trinity. The Triune God—Father, Son, and Spirit—together wills to save humanity in the manner of the cross. Jesus is not a hapless victim. Though he is handed over to sinners and appears inert during the passion, the truth is that he wills it himself (as does the Father) because he loves humanity. God, in Christ, maintains agency throughout the passion—he hands himself over, too. Rutledge insists on this point:

It is crucial to maintain the agency of the three [divine] persons and to remind ourselves that the whole enterprise is a transaction undertaken among the persons of the Trinity. The Son is not intervening to change the Father’s disposition toward us. His disposition toward us remains the same as ever—unfailingly determined upon our redemption.7

To avoid pitting the Father against the Son, liberals insist that the cross wasn’t the intention behind God’s rescue mission at all. Rather, they uphold it as a mere “moral example.” Jesus, in this view, loved God and others so much and so single-mindedly that he accepted the inevitable resistance of a sinful world. He never meant to die, and the Father never willed it—that would be cruel. Rather, Jesus was passive—just as he didn’t fight back against his persecutors, so too he didn’t forsake his mission of justice in the face of oppression. He was an accidental martyr.

Yet however much this salves our consciences, it’s not the Christian proclamation. The sense of scripture is that Christ shared God’s specific will that he undergo death on the cross. Here, Isaiah 53 in particular “serves as a guide or partial substructure for the New Testament as a whole,” Rutledge explains. “The passage gives strong support for the affirmation that the suffering of the Messiah is part of the plan of God for salvation revealed proleptically to ancient Israel.” The theological tradition agrees. Aquinas notes that Jesus both obeys a command from the Father and actively wills to do it himself. He’s not forced “to do something by a will that is exclusively the Father’s,” Von Balthasar states.

Moreover, Aquinas says that the Father inspired in Christ “the will to suffer for us,” so that God did not inflict a hideous death on an unwilling man. Jesus’ humanity shrunk at the face of death—he loved life. And, in his divine person, he didn’t want to become sin or experience separation from the Father (“Not what I will). But he also exists solely to do the Father’s will, which in this case was to undergo the passion for us (“But what you will.”). Rutledge sums it up well when she says that “the purpose of the incarnation was the offering of his entire incarnate life on the cross.”

Substitution implies a change in God’s being. This objection is related to the first. When construed in a crude manner, substitution paints a picture of a fickle, weak deity: God creates us in love, but then (to his surprise) we rebel in sin, which makes him angry. In response, he threatens to punish us with annihilation and death. But on the cross, Jesus takes the blow in our stead. God then works out his wrath on his Son, and then once again looks on us kindly.

At his most extreme and rhetorical, Calvin sounds like this. But, obviously, if this were a literal claim, substitution would be unacceptable. God never changes in his disposition toward creation and humanity, as Rutledge hinted at just now. She expounds on this further:

God is not divided against himself. When we see Jesus, we see the Father (John 14:7). The Father did not look at Jesus on the cross and suddenly have a change of heart. The purpose of the atonement was not to bring about a change in God’s attitude toward his rebellious creatures. God’s attitude toward us has always and ever been the same. Judgment against sin is preceded, accompanied, and followed by God’s mercy. There was never a time when God was against us. Even in his wrath he is for us. Yet at the same time he is not for us without wrath, because his will is to destroy all that is hostile to perfecting his world.8

Again, this is a joint project of the Trinity decided upon from all eternity. Rutledge continues:

God does not change; least of all does he change as a result of the self-giving of the Son. This is a central affirmation. The event of the cross is the enactment in history of an eternal decision within the being of God. God is not changed by a historical event but has always been going out from God’s self in sacrificial love.9

Here is where the Last Supper and the eucharist play an important role. With the Passover meal, Christ reveals the meaning behind the cross. The crucifixion is itself a revelation of God’s being: God is self-gift, in his very nature. Jesus washes his disciples feet in John to underscore this symbolism.

Substitution endorses an angry God. This, in my experience, is the crux of the resistance to the substation motif. It’s not rational—it’s purely emotional. Many contemporary Christians, as we noted before, are terrified of the notion of God’s wrath. Whether in reaction to a harsh form of Christianity from earlier generations, or simply because they want a cuddly, Care Bear deity, liberal Christians today preach almost nothing but a vague, bland slogan of love—one evacuated of all depths.

So when we come to passages in the Bible that talk of wrath, many of us skip them or stop dead in our tracks, unable to process the language. It triggers us, to borrow a popular term. “It makes many people queasy nowadays to talk about the wrath of God,” Rutledge confesses, “but there can be no turning away from this prominent biblical theme. Opressed peoples around the world have been empowered by the scriptural picture of a God who is angered by injustice and unrighteousness.”

To work around wrath, some liberals unwittingly adopt the heresy of Marcionism, believing that an angry God is a product of the Old Testament; whereas, in the New Testament, Jesus reveals God as loving kindness and compassion. Thus we can ignore the Old Testament and just focus on the New. This is wrong on multiple levels. To begin with, the Old Testament depicts God as love from beginning to end. Christ gets his commandment to love God and neighbor from Leviticus, after all. God’s love isn’t “unconditional”—he has expectations for his People—but it is “steadfast.” God’s always there to take us back.

Secondly, Jesus, to quote a divinity school professor of mine, is not a “nice guy.” Yes, he’s inspiring, charismatic, and deeply compassionate toward the poor and outcast. But he’s got elbows, and he throws them. He gets angry in many places, in constant conflict with the authorities. He pronounces woe to the rich and powerful; drives out money changers from the Temple with a whip; and has sharp words for his disciples. We understand this anger as his righteous indignation at sin and injustice. Clearly, scripture portrays Jesus’—and thus God’s—wrath as a function of his love, not in opposition to it. Rutledge builds on this idea in several dense quotes:

It is essential to read the “wrath of God” as symbolic language. It is a figurative way of expressing the eternal opposition of God to all that would hurt and destroy his good creation.

And later:

The biblical message is that the outrage is first of all in the heart of God. If we are resistant to the idea of the wrath of God, we might pause to reflect the next time we are outraged by something—about our property values being threatened, or our children’s educational opportunities being limited, or our tax breaks being eliminated. All of us are capable of anger about something. God’s anger, however, is pure. It does not have the maintenance of privilege as its object, but goes out on behalf of those who have no privileges. The wrath of God is not an emotion that flares up from time to time as though God had temper tantrums; it is a way of describing his absolute enmity against all wrong and his coming to set matters right.

As she suggests, liberals should really defend the wrath of God. Scripture clearly indicates that God is angry about injustice done to the poor—a cause dear to the heart of liberals. Think of the outrage we feel over Putin’s war crimes in Ukraine—the fury that rose in our hearts when we saw those photos of massacred civilians in Bucha. If God—perfect righteousness—can’t experience wrath over sin, who are we to feel angry about anything? Rutledge emphasizes this idea:

In our own day, in our haste to flee from the wrath of God, we might ask whether we have thought through the consequences of belief in a god who is not set against evil in all its forms. Miroslav Volf writes, “A non-indignant God would be an accomplice in injustice, deception, and violence.”

Nadiya Trubchaninova, 70, sits next to the body of her son Vadym, 48, killed by Russian soldiers in Bucha, Ukraine. But doesn't God forgive? Yes—through the cross, not above it. Rutledge puts it thus:

Forgiveness in and of itself is not the essence of Christianity, though many believe it to be so. Forgiveness must be understood in its relationship to justice if the Christian gospel is to be allowed full scope. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa has said, “Forgiveness is not cheap, is not facile. It is costly. Reconciliation is not an easy option. It cost God the death of his Son.”

The wrath of God flows from his justice. “God’s justice, as Tutu insisted, is not retributive but restorative,” she continues. “It is natural that many do not understand this, because ‘God’s love, resisted, is felt as wrath.’”

How does this relate back to Jesus? In several places, the Bible describes God’s judgment as “the cup of wrath.” In the Gospels, Christ speaks of going to the cross as drinking from this cup—the passion is where the cup of God’s wrath gets poured out upon him. He asks his disciples if they can drink from that cup, too. When he has them drink the cup at the Last Supper, it’s a symbolic enactment that they will share in his sacrifice.

If talk of God’s wrath scares us, then, we should turn to the cross. For the cross is, among other things, the place where God pours out God’s wrath—not on us, but on himself. That is the extraordinary action of Jesus in taking our place. Rutledge puts it thus:

The crucifixion reveals God placing himself under his own sentence. The wrath of God has lodged in God’s own self…The wrath of God falls upon God himself, by God’s own choice, out of God’s own love.10

VI.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, we pray you to set your passion, cross, and death between your judgment and our souls, now and in the hour of our death. Give mercy and grace to the living; pardon and rest to the dead; to your holy Church peace and concord; and to us sinners everlasting life and glory; for with the Father and the Holy Spirit you live and reign, one God, now and for ever. Amen. (From the Book of Common Prayer, Good Friday)

If you’re a liberal and you’re still reading this, I imagine you’re shaking your head “no” vigorously. If you’re conservative, probably the opposite—perhaps to an unhealthy degree. As I said earlier, our reaction to substitution has more to do with temperament than reason. As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has demonstrated, liberals base their unconscious morality mostly on one principle: care. They value caring for others over all other considerations, particularly those whom they consider victims in society. Any theology, therefore, that smacks of an angry God punishing us—let alone Jesus—for sin repels them on a gut level. They much prefer the idea that Jesus, on the cross, has solidarity with the outcast.

Conservatives, on the other hand, value principles like obedience, purity, and loyalty as well as compassion. You can see, then, why they might be comfortable—too comfortable—with themes of chastisement, blood sacrifice, and retributive justice. Their emotions prime them toward the opposite danger—making the crucifixion a perverse justification for the death penalty, authoritarianism, policing, etc. You get this feeling from folks at sporting events who flash signs with “John 3:16” emblazoned on them. I agree with the scriptural statement, but in their hands it feels like some kind of threat. To affirm substitution is not to endorse human systems of control and punishment.

We shouldn’t be too hard on ourselves for getting this stuff wrong. The idea of a suffering Messiah struck the disciples themselves as absurd. Despite passages like Isaiah 53, the Old Testament didn’t overtly foretell such a savior. After Easter, on the road to Emmaus, Jesus himself has to illuminate the scriptures for his interlocutors so that they come to see its truth:

Oh, how foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have declared! Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and then enter into his glory?

Even after centuries of reflection, though, Christians struggle to accept this shocking idea. Over at Pope Francis Generation, Paul Fahey wrote a reflection on the cross last November. It’s very beautiful in places, but it’s troubling to watch him dismiss the notion of substitution and, even more, the wrath of God. “Jesus's death didn't satisfy the Father's wrath,” he concludes, “it fully revealed God's love for each of us.” Doesn’t it do both?

I’m not saying the Bible gives these ideas equal weight. The love of God predominates. No religious text depicts God as love more than the Bible—the parable of the Prodigal Son has to be the most beautiful description of the divine ever composed. But that same book shows that, on the cross, God’s love is somehow related to his wrath.

When I pressed Fahey on this point, however, a friend of mine sprung to his defense. “I cannot accept penal substitution because of what it implies about the Father,” my friend said. “My objection is the idea that the Father would rain down God’s wrath on Jesus as a substitution for us. What a gruesome image that is of the Father. God does not will suffering.” When I suggested my friend read Rutledge’s book, the idea was rejected out of hand. This person’s mind was so closed to the notion that it couldn’t even consider an alternative view.

My friend’s an exceedingly holy, prayerful person and will sail into the Kingdom way ahead of me. Yet something essential is being denied in these statements. They bring to mind theologian Richard Niebuhr’s caricature of liberal Christianity:

A God without wrath brought men without sin into a Kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a Cross.

If ideas like substitution stir up psychic baggage in us, we might seek professional counseling (I benefit from it every week). But what we can’t do is turn Christianity into moralistic therapeutic deism to comfort ourselves. And, anyway, substitution isn’t supposed to mortify us like some flagellate. As Rutledge takes pains to insist, the desirable reaction for a Christian is gratitude, even joy:

This evangel has a very specific outcome: it shows how Christ assumed the weight of sin and guilt that lies upon the human spirit precisely in the moment that the weight is lifted, and it therefore powerfully evokes from us a feeling of thanksgiving so profound that we no longer need to avoid accountability, but gladly embrace it.11

Look, substitution is hardly my favorite theme in theology. As Rutledge says, we mustn’t single it out as the only idea at work in the passion. We have to keep all eight motifs in play, especially Christus Victor. But we can’t excise it, either, just because it offends 21st-century sensibilities. It’s part of the story of salvation, a key part. I wouldn’t preach the atonement most Sundays out of the liturgical year, God knows. And when I would, I’d be sensitive and careful.

Yet there are certain seasons of life and days on the calendar that call for—even demand—that the church proclaim this truth from the pulpit. Particularly in a culture as religiously illiterate as our own, and to believers who lack a basic understanding of the fundamentals of the faith. Lent is a great opportunity, especially Holy Week. Pastors may be nervous about making an attempt—it’s easy to do damage with these ideas. The crucifixion is strong medicine. But I think we can take it.

The cross is tragedy. And the cross is triumph. It’s double-sided. A theology that ignores either of these moods does a disservice to the drama. As another professor of mine once said, “The story of the Gospels is that God comes to us and we kill him.” At the conclusion of the Good Friday liturgy in the Anglican communion, the congregation sings a haunting 1630 hymn from Johann Heermann, “Ah, Holy Jesus, How Hast Thou Offended?” It’s lyrics bring home the centrality of the cross in ways that escape many mainline preachers:

Lo, the Good Shepherd for the sheep is offered; / The slave hath sinned, and the Son hath suffered; / For our atonement, while we nothing heeded, / God interceded.

We rich, comfortable, self-satisfied Christians in the West could do with a taste of substitution every once in a while. It wouldn’t do us harm. It might just save our lives.

Fleming Rutledge, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids: 2015) 464.

“The Atonement Paradigm: Does It Still Have Explanatory Value?” Lisa Sowle Cahill, Theological Studies (68) 2007: 424.

Rutledge, 471. Sarx is often translated flesh, but it really means “the human being under the reign of Sin.”

Rutledge, 503.

Rutledge, 136.

Barth, Church Dogmatics, Vol IV/1, quoted in Rutledge, 517.

Rutledge, 280.

Rutledge, 282.

Rutledge, 500.

Rutledge, 132,

Rutledge, 530.

I appreciate the reply. Before I respond, let me say I found your substack from a link Andrew Sullivan included to your Power of the Dog post. It was so refreshing to read your view on a film I also think was way overhyped and full of narrative holes. Anyway, speaking of narrative holes; when I talk about Atonement, I tend to stress 2 points. 1) the fact that there are numerous views on the cross in scripture is not surprising. I love this quote from Peter Enns: “The Christian faith has as its center piece a beaten, tortured, and crucified king. But, here’s the thing. If you wanted to create a religion at any time in history – this would probably not to be your first move. I mean, who’s going to believe this stuff?” So, Paul, the Gospel writers and others had to figure out the “unbelievable” using the historically available Jewish worldview they shared. So, a combination of blood atonement, a suffering Savior, victory over sin and/or spiritual powers, sacrificial obedience, etc were available and combined in such a way that made sense to (a few) Jews and quite a few more “Yahweh curious” gentiles. This was later expanded upon and combined with a metaphysics derived from Greek philosophy at first, and then a more individualistic Enlightenment view in the 16th -17th centuries, then on to now. The point is that people have tried to faithfully and thoughtfully “figure out” the cross for 2000 years using historically available categories. Some “work” better than others, given current circumstances. But, they all point to the divine rescue mission Jesus carries out to reconcile God and humanity. And not just to “save” my own little sin-sick soul from hell — but ultimately, all of creation. Phew! 2) I focus my attention on a Moltmannian view of a Crucified God — and the revelation of the self-giving love at the core of the divine. Then, I can use that to speak about how faith can be manifest in acts of love in response, and how the Spirit works in us by the power of love to shape our faith and actions. There’s more to it than that. But that’s plenty for now. I also use lots of poetry, metaphor and imagery — and try to avoid jargon.

Nick, I really appreciate this post. Like you, I don’t fall easily into niches; never have — especially when I could be categorized as a “Socialist Evangelical” in the 1980’s (not an easy place to be back then). Now I’m a mainline pastor, who finds much theological liberalism to be limp (as did the Niebuhrs), while Protestant conservativism is way too individualistic and groveling before an”angry” God. I must say, however, that as logically coherent as your argument is, it still leaves me somewhat “cold.” I crave a theology that “makes sense” in some ways, but also does not turn God into a person who is reducible to rational categories; a calculating homo economicus writ large, if you will. Still, I appreciate your efforts here to connect wrath and love in a way that “works,” but also leaves room for irreducible mystery.