On Easter Sunday, The New York Times published an op-ed by conservative columnist David French entitled, “Easter Rebukes the Christian Will to Power.” French is a self-described orthodox evangelical Christian, orthodox here standing in opposition to white Christian nationalism, which (in his view) has perverted authentic evangelicalism into an idolatrous MAGA cult. As he put it recently on Firing Line, Donald Trump’s converted evangelicalism far more than the other way around. The Times column continues this critique, as he chastises the Christian right for harboring “the spirit of Barabbas,” the criminal who’s exchanged for Jesus during the Passion:

The spirit of Barabbas tempts Christians even today. You see it when armed Christians idolize their guns, when angry Christians threaten and attempt to intimidate their political opponents, when fearful Christians adopt the tactics and ethos of Trumpism to preserve their power. The spirit of Barabbas most clearly captured the mob on Jan. 6, when praying Americans participated in an insurrection based on a lie.

French equates these Christians with Barabbas in order to condemn them for their increasingly anti-democratic, lawless means of seizing control of the government. In this, he’s spot on. But he goes further, arguing that the fundamental error on the part of such fascists is that they’ve forgotten that Jesus’ kingdom is “not from this world.” Christ “wasn’t a political leader,” French says, “even though the people hoped for political liberation.” Jesus rejects Satan’s offer of the world’s kingdoms, he points out, and likewise stops Peter when the disciple wields the sword in Gethsemane. Christ’s purpose “was to go to the cross,” French concludes—earthly power wasn’t the point.

This reading of the Gospels pervades the minds of most American Christians today, especially those who (like me) are well-fed, well-heeled, and live in relative freedom. With sleight of hand, it makes two false moves: first, it spiritualizes Jesus’ mission; it divorces his life and death from history and turns his preaching of the reign of God into a poetic idea. The kingdom’s not about our lives here on Earth, but going to a non-corporeal heaven when we die (somewhere way far away). Secondly, it’s an individualist reading; it reduces the Gospel to one’s interior state before God. Personal relationship—accepting Jesus as “my” Lord and Savior—is what matters. Paul’s message of justification by faith gets watered down to the affective mood of particular believers. Social ethics are, at best, secondary—an optional add-on.

To French’s credit, he acknowledges that Christians are called to work for a better world. “Believers are required to ‘act justly,’” he says. “We should not stand idly by in the face of exploitation or oppression. We do not retreat from the public square.” And the example he gives is one I’d point to myself: the Second Reconstruction of the 1950s and ‘60s. “The single most consequential movement for American justice in the last century,” he says, “was influenced and empowered by the Black churches in the South.” This is a point lost on many leftists today. It’s impossible to make sense of the civil rights movement—especially its belief in redemptive suffering—outside of its Christian worldview. Rev. King’s rhetoric and those of other leaders was saturated with biblical imagery and ideas.

Yet French would have us believe, somehow, that these efforts either weren’t political or weren’t directly linked to the evangel of Christ. That’s the tenor of his argument when you game it out. But there’s a blatant problem: the civil rights movement was explicitly Christian and political. King and his followers believed their struggle for the vote and equal treatment under the law—express political demands—were the logical consequence of discipleship. And the strategy and tactics they practiced were the immediate application of Christ’s teachings to their situation. They weren’t adapting some vague, generalized ethical instructions from Jesus, as French might contend. No, they saw in the words and example of the carpenter from Nazareth (mediated through Tolstoy) an explicit command to engage in civil disobedience to the state. Since the time of slavery, the Black church has always seen the Gospel—and the entire Bible—as the Good News of our collective liberation here and now. And it’s this theology, not that of French (and most white Christians), that’s true to God’s revelation.

II.

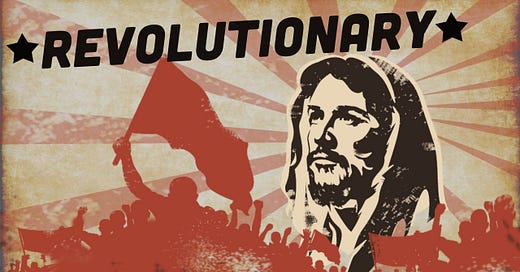

This claim finds firm footing in two books that share a title: The Politics of Jesus. The first, from 1972 , belongs to the late Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder.1 The second, from 2006, was written by Obery Hendricks, an influential biblical scholar and an Ordained Elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Coming from different ecclesial traditions, Yoder and Hendricks arrive at the same thesis: that Jesus is revealed by scripture as the model par excellence of radical poltical action. His ministry and teachings “are best understood as presenting to hearers and readers not the avoidance of political options,” Yoder says, “but one particular social-political-ethical option.”2 Hendricks puts it more powerfully:

To say that Jesus was a political revolutionary is to say that the message he proclaimed not only called for a change in individual hearts but also demanded sweeping and comprehensive change in the political, social, and economic structures in his setting in life: colonized Israel. It means that if Jesus had had his way, the Roman Empire and the ruling elites among his own people either would no longer have held their positions of power, or if they did, would have had to conduct themselves very, very differently. It means that an important goal of his ministry was to radically change the distribution of authority and power, goods and resources, so all people—particularly the little people, or “least of these,” as Jesus called them—might have lives free of political repression, enforced hunger and poverty, and undue insecurity. It means that Jesus sought not only to heal people’s pain but also to inspire and empower people to remove the unjust social and political structures that too often were the cause of their pain. It means that Jesus had a clear and unambiguous vision of the healthy world that God intended and that he addressed any issue—social, economic, or political—that violated that vision.3

Such a reading of the Gospels stands in broad agreement with the liberation theology of South and Central America, but for one major difference: unlike that strain, it maintains a high Christology, i.e., it integrates its understanding of Jesus as a social revolutionary with the Chalcedonian confession of Christ’s divine personhood and human nature. Jesus of Nazareth was the Messiah, the Incarnate Word. To encounter him was to encounter the second person of the Trinity. And in his incarnate life, the Son of God poured himself out to free his people from political, spiritual, and economic bondage. Hendricks states as much: "Jesus Christ was 'made flesh and dwelled among us,' as John’s Gospel puts it, to model and set into inexorable motion the way of liberation of mind, body, and soul from the tyranny of principalities and powers and unjust rulers in high places."4

Yoder concurs, putting the matter more systematically:

Jesus was, in his divinely mandated (i.e., promised, anointed, messianic) prophethood, priesthood, and kingship, the bearer of a new possibility of human, social, and therefore political relationships. His baptism is the inauguration and his cross the culmination of that new regime in which his disciples are called to share…There is no difference between the Jesus of Historie and the Christ of Geschicte, or between Christ as God and Jesus as Man, or between the religion of Jesus and the religion about Jesus (or between the Jesus of the canon and the Jesus of history). No such slicing can avoid his call to an ethic marked by the cross, a cross identified as the punishment of a man who threatens society by creating a new kind of community leading a radically new kind of life.5

Contra French, Jesus differed Barabbas in one respect only: the use of force. Barabbas, the evangelists tell us, was imprisoned for “murder committed during an insurrection.” Christ disavows such violence, absolutely. Waging a holy war against Rome and the corrupt Jewish authorities was a real, constant option for him; he wrestled with it through the Passion. Time and again, he renounced the path of the Zealots not just tactically, but on principle. Yet—and this is the crucial point—he shared their goal. He aimed for social revolution; he fomented a direct confrontation with the state. Like Rev. King, he did not seek power for himself, only freedom for his people. And he did so through active, non-violent resistance. The Spirit of Jesus is not one of withdrawal or conformity or spiritual quietism. It’s the Spirit of God’s justice, which destroys the sin of Empire through a catastrophic upheaval. This eruption brings history—political history—to a dramatic climax.

The announcement of the Messiah as liberator comes right off the bat in Luke’s Gospel. There, both Zechariah (the father of John the Baptist) and Jesus’ mother, Mary, anticipate the births of their sons as the fulfillment of the people’s eschatological expectations—the belief that Yahweh would return as king, gather Israel, throw off their foreign rulers, and establish justice on earth. It’s always baffled me how the Catholic Church, which venerates Mary to an obsessive degree, mutes the radical nature of her longest speech. In the Magnificat, Yoder says, “we are being told that the one whose birth is now being announced is to be an agent of radical social change.”6 Lest their be any doubt about his intentions, Jesus proclaims his revolutionary agenda when he reads from Isaiah in synagogue:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Hendricks analyzes the constitutive elements of this mission statement one by one:

Good news to the poor. Jesus announces that the reason for his ministry is to struggle for radical change in the circumstances and institutions that kept the people downtrodden and impoverished. Only radical change could make a real difference in their plight.

Release to the captives. This declaration of mercy for those unjustly incarcerated was explosive. Roman jails were full of political prisoners and those reduced to penury by economic exploitation.

Freedom for the oppressed. This was the ultimate political pronouncement: liberation to those crushed by the weight of colonial empire.

Year of Jubilee. To proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor was to announce the coming of the Jubilee. This was a law in Leviticus that decreed all land that had been confiscated or lost by the people through debt peonage be returned to its original owners every fifty years.7

This is a political manifesto from Jesus, not just spiritual. It essentially decrees Year Zero, a leveling of all inequality and a reset of economic life. This was to be a visible restructuring of socio-political relations among the people of God, achieved by divine intervention in the person of Jesus as the one Anointed by the Spirit. Yoder draws the profound implications:

We must conclude that in the ordinary sense of his words, Jesus, like Mary and like John the Baptist, was announcing the imminent implementation of a new regime whose marks would be that the rich would give to the poor, the captives would be freed, and the hearers would have a new mentality (metanoia), if they believed this news.8

We’ll explore the Jubilee Year in a subsequent post. But this is something that modern, post-Enlightenment readers must get through our heads: in the ancient world, people did not differentiate religion from politics. The Bible, including the New Testament, makes no such distinction. It was all one and the same. The idea of a wall of separation between church and state “is familiar enough to us,” N.T. Wright says, “but Jesus’ world remained innocent of it.”9 Such a notion would’ve struck them as absurd; it would be like if we tried to communicate with an extraterrestrial. The cosmology of their age was utterly different from ours.

And it was this cosmology that animated Jesus: one in which heaven and earth, the divine and the human, the political and the spiritual, interpenetrated and intermingled. His announcement of the Year of Jubilee was to proclaim the reconstitution of socio-economic-religious relations in Israel, the kingdom come. “What is Caesar’s and what is God’s are not on different levels, so as never to clash,” Yoder says, “they are in the same arena.”10 To announce God’s reign, then, is to declare the downfall of Caesar’s.

But why did Christ feel compelled to do this? What had happened to God’s people that this moment, more than any other, demanded the Messiah’s advent and assault on the regnant regime? To understand, we’ve got to go through the story of Israel and attend to the political developments that had brought them, as in ages past, to a state of slavery.

III.

Before we do, though, we must situate the narrative inside the Bible's vision of politics. This starts with the acknowledgment that governments—and all social systems—are not inherently evil or a mistake. On the contrary, they’re part of God’s good creation. Everything was made through the Word, Christians confess, and holds together in him. “This ‘everything’ that Christ maintains united is the world powers,” Yoder says. “It is the reign of order among creatures, order which in its original intention is a divine gift…Society and history, even nature, require regularity, system, order—and God has provided for this need.”11

Yet because of our rebellion, humankind wanders in exile from God and has no access to that good creation. “The creature and the world are fallen,” he continues, “and in this the powers have their own share…These structures which were supposed to be our servants have become our masters and our guardians.” They aren’t totally wicked; they still serve an ordering function and God can use them to accomplish his divine purposes. But they’ve brought us to a place of slavery, idols that have set themselves up as absolutes that demand our obedience.12

‘Powers,’ by the way, is the New Testament’s shorthand for a host of social structures: organized religion; intellectual traditions and ideologies; moral codes and customs; and the elements of political economy, e.g., legislatures, courts, markets, schools, corporations, the nation-state, etc. All of these systems are made up of individuals, but they're more than the sum of their parts. And that “more” is an invisible Power. We can’t live without them—there would be no history, no society, no humanity itself unless we had them. Yet we can’t live with them, either—we lie in their grip, a state of domination that cannot, it seems, be undone from within. In this, the invisible Power feels existential, cosmic, metaphysical.13

Such tyrannical Powers, even if they look “normal” to us, are an affront to God’s sovereignty. If God reigns, then he reigns over society, not just individuals. To save us, then, in our all our humanity, the Powers cannot simply be destroyed or set aside or ignored. God must break their sovereignty. This is what Jesus did, concretely and historically, in his free life and subversive death.14 As Yoder puts it, Jesus “did not say (as some sectarian pacifists or some pietists might), ‘You can have your politics and I shall do something else more important’; he said, ‘your definition of polis, of the social, of the wholeness of being human socially is perverted.'”15

The confession by the early church of Jesus as “Lord,” then, wasn’t (contra contemporary thought) a statement of personal affection or intimacy or reverence. It was an affirmation of Christ’s victory over the Powers of the cosmos. And it remains that—the declaration of a social, political, structural fact. Jesus is Wonder Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. The government, as Isaiah prophesies, shall be upon his shoulders and no one else's, be they a party or premier or president. To deny the political aspect of these titles is to deny his Lordship; it’s to assert that the God of the universe somehow doesn’t exercise authority over the stewardship of his creation.

The church is called to live this truth out not through mere charity, but by making known to today's principalities that Jesus has defeated their rebellion and destroyed their pretense, and by laboring for a political order that gives God’s people—all of them—abundant life.16 To do so authentically, it must establish justice within its own polity, too, as Hendrikus Berkhof brilliantly puts it:

All resistance and every attack against the gods of this age will be unfruitful, unless the church itself is resistance and attack, unless it demonstrates in its own life and fellowship how believers can live freed from the Powers. We can only preach the manifold wisdom of God to Mammon if our life displays that we are joyfully freed from his clutches. To reject nationalism we must begin by no longer recognizing in our own bosoms any difference between peoples. We shall only resist social injustice and the disintegration of community if justice and mercy prevail in our own common life and social differences have lost their power to divide.17

Building—and losing—such a just society was the story of Israel. And it’s to that tale, and Christ’s revolutionary role in it, that we turn next.

Yoder, who died in 1997, was accused of sexually assaulting dozens—possibly over 100—women in his career. As in the Roman Catholic and Southern Baptist churches, the abuse was initially covered up by the Anabaptist leadership. In 2014, the church created a task force to investigate and produced a report, which you can read here. Some may be able separate Yoder’s crimes from his theological convictions. Others may—with justification—decide that such a position is morally untenable. For the purposes of this essay, I’ve adopted the former position. But I leave it for readers to come to their own judgment.

John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus, second edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994), 11.

Obery M. Hendricks, Jr., The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Nature of Jesus’ Teachings and How They Have Been Corrupted (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 6.

Hendricks, 10.

Yoder, 52-53.

Yoder, 22.

Hendricks, 8.

Yoder, 32.

N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 296.

Yoder, 44-45.

Yoder, 141.

Yoder, 141-142.

Yoder, 142-143.

Yoder, 144-145.

Yoder, 107.

Yoder, 156-157.

Hendrikus Berkhof, Christ and the Powers, quoted in Yoder, 148.

Excellent. The Good News ain't news from nowhere--that is, it is not utopian, it's grounded in the lived experience of a real human being who taught us what real equality and the grace that goes with it might look like. But as God, as Spirit, he (or whatever pronoun you prefer) is the unknowable Other as well. There is a difference, and it's worth holding onto and living with, no matter how paradoxical it sounds, for it opens the way to treating all Others as your equal.

I sure learn a lot of new words related to religion when I read these. I like the message of social justice and your arguments are persuasive. I think cleaning up their own "houses" is the first step and we are far from that.