I. The Abundance Agenda

Over 2,000 verses of the Bible speak of social justice. Put together, they paint a vision of how we, God’s creatures, are to order our political economy to align with divine intentions. That vision, as Edith Rasell explains in her recent book The Way of Abundance: Economic Justice in Scripture and Society, consists of five core ideas:

The Earth Is the Lord’s. The Bible reveals that everything we have comes from God. The creation stories of Genesis paint a world fundamentally dependent on the Creator. We—as individuals, as nations—do not own the earth. We’re temporary tenants, only passing through (Lev 25:23). “The earth and its fullness are the Lord’s,” writes Paul (1 Cor 10:26). Without God’s gifts, we do not exist. We have nothing, produce nothing, are nothing. “Indeed, the whole earth is mine,” Yahweh says (Exod 19:5).

God Gives Us Abundant Material Resources. The vision of scripture is a vision of abundance. Creation is a bounteous gift, overflowing with richness (Deut 8:7b-10). With God’s blessing, all parts of creation prosper (Lev 26:3-5). God intends for the human family to have all we need—not just to survive, but to thrive, to “flourish as a garden” (Hos 14:7b). Jesus symbolized God’s reign as a lavish banquet to which everyone’s invited and everyone fed (Matt 22:1-10; Luke 14:16-24). God’s creation provides more than enough for all.

God Cares About All Aspects of Life. As physical-spiritual creatures, all aspects of our being matter to God. The Exodus story reveals that the Lord is concerned for our material, emotional, and social welfare. God loves us and seeks our health. And since oppression is both physical and spiritual, God’s rescue is also physical and spiritual. “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly,” Jesus says (John 10:10).

God’s Intentions for God’s Resources. During our sojourn as God’s creatures, in God’s creation, we’ve been called to the sacred responsibility of exercising stewardship. We must discern and live out God’s wishes for how to cultivate and administer the resources the Lord’s provided (Luke 12:48). We’re accountable to the Creator and bear solemn obligations for how we organize society (Matt 21:33-46; Luke 12:42-48). When some of members of the human family receive too small a share of the abundance in our midst and fail to thrive, we thwart God’s purposes and betray our vocation.

God Requires Justice.

The Bible ascribes many attributes to God, but the primary one is justice (Jer 9:24; Ps 89:14; Ps 33:5). “Justice connotes more than individual piety,” Obery Hendricks says. “It also means holistic, collective—that is, social—righteousness.” In a similar vein, Walter Brueggemann argues that distributive justice is the central teaching of the Bible: “Justice is to sort out what belongs to whom, and to return it to them. Such an understanding implies that there is a right distribution of goods and access to the sources of life. There are certain entitlements that cannot be mocked.” Likewise John Dominic Crossan: “The primary meaning of ‘justice’ is equitable distribution of whatever you have in mind…Do all God’s children have enough? If not—and the biblical answer is ‘not’—how must things change here below so that all God’s people have a fair, equitable, and just proportion of God’s world?”

Related to God’s justice is the Hebrew word hesed, which occurs some 240 times in the Old Testament. It’s commonly translated as “steadfast love,” but in context it doesn’t mean sentiment or feeling, but actions—actions that bring about the well-being of others. That’s the kind of love God is: more a verb than a noun. To do hesed as a society, then, means that “every political decision must be based on what is best for the masses, on what their real needs are,” says Hendricks. “Our allegiance must be to crafting policies with our neighbors in mind, to listening and contemplating the people’s challenges and needs with prayer and humility.”1

God doesn’t grade nations on a curve. When it comes to enacting social justice, it’s pass/fail. The Lord doesn’t look at 40 million poor people or 11.5 million unemployed people or 1 in 8 children going hungry in the United States—the wealthiest empire in history—and think, “Exceptional!” On the contrary, as Isaiah proclaims, he’s appalled and infuriated by such degradation. He vows to fight oppression and avenge the poor. God loves all, but in our war on the indigent, he takes a clear side.

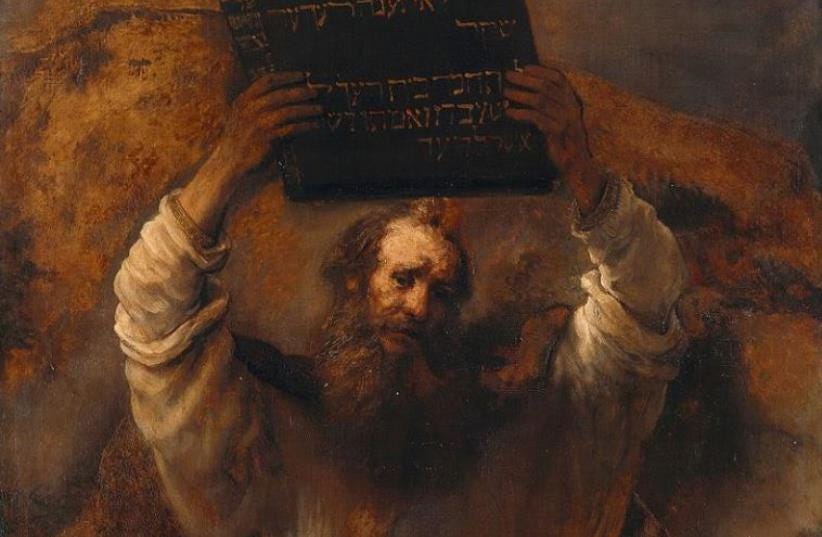

Yet the Good News is that the Lord’s also provided an instrument to guide us in establishing justice: the Law. Far from an onerous burden, the Law is a gift to entice us into more fulfilling and joyful lives lived in communion. In its original form, the Law is “a means by which the divine ordering of chaos at the cosmic level is actualized in the social sphere,” as Terence Fretheim says.2 It was through obedience to the Law, Bruegemann adds, that Israel “was able to participate in the ongoing revolution of turning the world into it’s true shape of God’s creation.”3

The Lord’s vision for the economy is eternal, unchanging through the ages. But the specific statutes and instructions God commands develop over time in the Bible to adapt to changing circumstances. It’s an evolution that played out over the course of Israel’s political history, a history to which we now turn.

II. The Age of Equals: Democratic Israel

Israel’s origin story was that of Exodus, which begins with their slavery in Egypt, the Bible’s ur-empire. In an act of epic political emancipation, their god—Yahweh—destroys Pharaoh and his hosts and leads the Hebrews dry-shod through the Red Sea. During their testing in the wilderness, this Lord of liberation forms them into a people meant not to be his slaves (in contrast to the gods of their neighbors), but a light unto the nations: they’re to live in right relationship with him and each other, making Yahweh alone their god and practicing justice. All this is to be done in freedom. As Hendricks puts it, “the seminal importance of the Exodus event is that in God’s response to the class oppression of the Hebrews, God posited justice and liberation as the very foundation of biblical faith.”4 Yahweh’s identity as a god of deliverance undergirds the people’s egalitarian ethos: they’d been delivered from bondage in Egypt, so they are not to oppress anyone among themselves.

According to Rasell, the diverse peoples who became the Israelites—at least some of whom really had escaped Egyptian slavery—settled the highlands of Canaan in the 13th century BCE. Over the generations, they developed a society characterized by some 250 to 300 self-sufficient settlements made up of clans of 100 to 300 relatives. They were very much a horizontal people, providing mutual support and sharing resources in reciprocal relations of kinship. This communalist behavior contrasted with the stratified societies of neighboring Canaanite cities. No one was rich, but no one lacked essential material resources—every family worked their land and produced what they needed. They were obligated to care for each other and uphold the welfare of their kinfolk.5

Justice was the Israelites central focus, and they believed that Yahweh’s laws specified economic and social practices that, if followed, would lead to the good society. This started with the distribution of land, which was accorded to families based on need—larger parcels to larger families, smaller parcels to smaller ones. The land was never to be bought or sold as a commodity (Lev 25:23). Instead, it was distributed by (drum roll, please) democratic lotteries! Yes—God commands sortition. This practice allowed Yahweh to determine the land’s final, equitable apportionment (Num 26:52-56; 33:54; Josh 14:2; 18:6, 8, 10; 19:51). Democratic lotteries ensured fairness and responsiveness to divine purposes.6

The Lord’s commandments for social justice continued with prohibitions on worshiping Canaanite gods, which would be to affirm that nation’s acquisitive, hierarchical, elite-dominated political economy. He laid down many anti-poverty statutes as well among the Israelites:

Their society was to care for widows, orphans, and the elderly (Exod 20:12; 22:22-24).

Their society was to provide loans to the poor without charging interest and with restrictions on how collateral was held and collected (Exod 22:25-27).

People who fell into debt bondage were to be released after six years of service, regardless if the debt was paid off (Exod 21:2).

Their society was to observe not just a Sabbath Day, when all economic activity would cease, but a Sabbath Year as well: every seventh year, the land—as well as the people and animals—were to rest from productivity (Exod 23:10-11).

The edict against coveting was meant to thwart the idolatry of consumerism, and that against stealing was intended to make enough communal possessions available so all could thrive.

There were laws against lying in judicial proceedings (Exod 20:16); exploiting the poor in lawsuits (Exod 23:6); and taking bribes in an official capacity (Exod 23:8).

Finally, the people were always to remember that they had once been aliens in Egypt—the word Hebrew literally means “immigrant.” Therefore, they were not to wrong or burden any immigrant or guest worker who chose to live among them (Exod 22:21; 23:9).

In terms of politics, multiple Israelite clans formed a tribe, and these tribes constituted a self-governing federation. Decisions were made democratically via a tribal council, with “judges” exercising temporary leadership in times of collective self-defense. These men were chosen based on one and only one characteristic: not their holiness or religiosity, but their willingness fight for the people’s freedom. There was no king or chief or even centralized government. Instead, Israel “chose to be a free and independent people with no ruling class to lord over it,” Hendricks says. Yahweh alone was sovereign. “In that time and place,” he continues, “the choice to bow to no king and pay tribute only to God was truly revolutionary.” He unpacks the significance of the Judges period as an enduring political model for Israel:

Malkuth shamayim—the sole sovereignty of God—became the basis for all the resistance movements in Israel to come. The radicality of this notion lay in its rejection of all human domination. Its impeccable logic was that if God is the sole king of the universe, no other claim to kingship is legitimate. For common people to declare that they would bow before no earthly king was a dangerous and radical statement in the ancient world and they knew it.7

III. The Age of Kings: Monarchical Israel

The Israelites maintained their democratic society for some 200 to 300 years. But as they faced increasing threats from the Philistines and others, their settlements became more complex and interdependent. This prompted them, in the eleventh century, to make a fateful choice: to institute a human monarch. It was a controversial decision, one that God himself opposed. Through the judge Samuel, Yahweh warns the people about what will happen if they crown a king: exploitation, militarism, oppression. “In that day you will cry out because of your king, whom you have chosen for yourselves,” Samuel tells them. “But the Lord will not answer you in that day.” They demand it, however, and the Lord at last acquiesces (1 Sam 8). That’s right—despite what you heard during the coronation of Charles III, God hates kings!

Unlike the judges, the new king (or messiah, anointed one) exercised permanent power. Still, he was answerable to God and shared the judges’ primary duty: to deliver the people from their oppressive enemies. First Saul, next David (the messiah par excellence), and then Solomon fulfilled this responsibility. But Solomon grew more and more corrupt in his old age, and his successors (as chronicled through both the prophetic and historical books) amounted to mediocrities at best, disasters at worst. What God warned the people of came to pass. The kings of Israel and Judah, Rasell notes, built lavish palaces where they reclined in opulence. They erected immense fortifications, glittering cities, and grand public structures—all monuments to themselves. They conscripted men into armies bent on conquest, and impressed them into unpaid labor on construction projects (1 Kgs 5:13-18; 12:1-20). This forced servitude took the peasants away from work on their farms, throwing their livelihoods into crisis.

As to that farming, it was transformed from diverse agriculture meant for families, into monocultural operations that produced cash crops for trade. Grains, olives, and grapes were cultivated on ever-larger estates and sold throughout the Near East. This commercial agriculture increased the value of the land, which became a source of great profit. Such lucrative real estate in turn caught the eye of the kings. Because they couldn’t buy it outright, they adopted alternative tactics. Sometimes they just seized the land from the peasants. Usually, though, they turned to a more devious weapon: debt.

When Israelite farmers fell on hard times, they were forced to borrow on credit until the next harvest, when they could repay the loan. This situation arose if more than one in four harvests failed, a frequent occurrence in the region’s arid climate. Often their only collateral was the land itself, which meant that if their crops continued to fail and they couldn’t repay their debt, their land was foreclosed on and their families evicted from their ancestral homes.

This happened with increasing regularity in Israel, yielding ever larger numbers of landless peasants and ever larger estates of wealthy creditors, including the kings. After losing their homes, many of these peasants were forced to live as tenant farmers and suffer the indignity of renting their old land. Others became unemployed laborers, toiling for a meager daily wage. All had to grow commodity crops for the market, which burdened them with the added absurdity of needing to buy food for their families. Rasell sums up the new, grim state of affairs thus:

The near universal thriving of the premonarchy era, when everyone was responsible for the well-being of their neighbors, was upended. Increasingly, society became characterized by hierarchy, domination, poverty for many, a precarious livelihood for many others, and extreme wealth for a very few. Abuse of the poor, loss of land, exploitation of workers, fraudulent commercial transactions, and dishonest judicial proceedings became more common.8

In response to this injustice, God took two actions: he called forth prophets and instituted new laws. The former served a crucial vocation—they were to preach the Lord’s justice to the kings and leaders, and witness to God’s power. It was a thankless, dangerous job. The super-rich they were sent to didn’t take kindly to being informed of God’s judgment, nor did the kings appreciate the call for repentance and obedience to the covenant. The new laws from this period appear in Leviticus and Deuteronomy. Many reiterated the previous laws of the democratic period. Others made fresh stipulations:

Gleaning. Any poor person, landless person, or immigrant was now allowed to glean, i.e., to enter into private land and avail themselves of food growing there. Farmers were to leave some portion of their crops unharvested for this purpose—blocking gleaning access to the poor was illegal. (Lev 19:9-10; 23:22. Deut 24:19-22)

Tithing for the Poor. Every third year, all farms were to bring one-tenth of their harvest to a central location, where it could be accessed and eaten by the poor. God called this tax a “sacred” portion. (Deut 14:28-29)

Debt Freedom. Laborers in debt bondage were to be released after working six years, even if the debt wasn’t paid. Moreover, the former master had to provide the newly emancipated person with resources to resume his life in freedom. Enslaving fellow Israelites was also banned. (Deut 15:12-15; Lev 25:39-42, 55)

Debt Cancellation. The abolition of debts every seventh year—the Sabbath Year—became formally prescribed. (Deut 15:1-2)

Sabbath Year. Resting from all economic activity every seventh year became a formal law. All Israelites, no matter their profession or status, were entitled to a sabbatical. Their rest superseded gross national product (Lev 25:1-7)

Fair Loans and Contracts. The law continued to prohibit charing interest on loans to the poor. The law also did not recognize “freedom of contract.” That is, it prohibited exploitative contracts that some parties were forced to adopt because of dire circumstances. “Work or starve” could not be the basis of an agreement.

Abolition of Poverty. God commanded the people to share with the poor so that everyone has what they need to live a life of abundance. Poverty was to be eradicated, no questions asked. (Deut 15:4-5, 7-8, 10-11)

Prohibition on Land Sales. The ban on selling land on the market was formally adopted. Land could be leased but not bought or sold, which was taken very seriously (as evidenced in 1 Kgs 21)

Land Redemption. If a family fell into debt and was forced to sell their land, one of their kin was legally obligated to buy the land back and return it to the clan. (Lev 25:25)

Year of Jubilee. Every fifty years, all lands that had become lost for any reason were to be returned to their original families. When Jesus announces a “year of the Lord’s favor,” this is what he has in mind. (Lev 25:8-17)

Anti-Corruption. The Law restated the ban on bribes (Deut 16:18-20) and added additional statutes against dishonest commercial practices (Deut 25:13-15a). Weights and measures for carrying out transactions could not be rigged (Lev 19:35-37), nor stones for demarcating land boundaries (Deut 19:14).

Living Wages. Workers had to be paid a living wage, which was to be given to them promptly at sunset—it was illegal to withhold wages. (Deut 24:14-15; Lev 19:13c)

Universal Citizenship. Strangers, foreigners, immigrants—all these “aliens” were to be treated as citizens of Israel. There was to be one law for all. (Lev 19:33-34; 24:22; Deut 1:16; 10:17-19; 24:17; 27:19) Aliens enjoyed the right to the Sabbath day and Sabbath year; to glean; and to access stored foodstuffs.

Rule of Law. No one—not even the king—was above the law. The king was instructed to keep a book of the law at his side and read it every day. (Deut 17:18b-20)

Love of Neighbor. The capstone and cornerstone of the Law was this: you shall love your neighbor as yourself (Lev 19:18b-19a). Jesus says this commandment sums up the entire Law, making it the foundation of all particular statutes. Israelites were to keep this spirit in their hearts, going beyond the simple letter of the law to its core principle.

The picture that emerges from these laws is that of generous welfare, regular leveling, and radical inclusion. “Israel as a community under obligation to Yahweh,” Bruegemann says, “is indeed a community of social revolution in the world.”9 The Law was meant to structure Israelite politics to enact God's reign on earth and let the people dwell in the presence of the Lord. It sought to overturn the injustices of the kings that were foreclosing so many from God's abundance. Yet as oppressive as their monarchs became over the centuries, the Israelites were about to find out a truth my Irish relatives never let me forget: it can always be worse.

Obery Hendricks, The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Nature of Jesus’ Teachings and How They Have Been Corrupted (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 111-112.

Terence Fretheim, Exodus, Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1991), 204.

Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1997), 200.

Hendricks, 15.

Edith Rasell, The Way of Abundance: Economic Justice in Scripture and Society (Minneapolis: Fortress Press), 8-10.

Rasell, 4.

Hendricks, 20.

Rasell, 29-31.

Brueggemann, 424.

Love how you worked in sortition. I think all the social justice issues you site etc are always aspirational.