Wages of Sin

The Justice of Affirmative Action

I. Land of the Free

On Thursday, January 12, 1865, an extraordinary meeting took place in Savannah, Georgia. The city had been liberated from rebel control just three weeks earlier by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and some 62,000 Union troops of the Army of the Tennessee, bringing his March to the Sea to a climax. “I beg to present you,” he wired President Lincoln, “as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.” That cotton, of course, had been picked by slave laborers, and during the general’s six-week blitz across Georgia, thousands of them flocked to the banner of the United States.

Unlike his boss, Ulysses Grant, Sherman was a virulent racist; he never agreed with emancipation and refused to obey Lincoln’s policy of enlisting Black men into the ranks. Like it or not, though, he found himself overseeing a biblical exodus of Freedmen, which had created a logistics nightmare. What to do with them? In response, Lincoln dispatched Edwin Stanton, his Secretary of War, to the fair city to be his eyes and ears on the ground. The President always craved first-hand information from the front, and Stanton’s visit would provide him valuable intelligence as he continued to develop his reconstruction policies.

Stanton urged Sherman to hold a conclave with twenty leaders of the city’s Black community. Almost all were ministers of various churches, ranging in age from mid-twenties to early seventies. Some were born free; most into slavery. As their representative to the President’s men they chose Rev. Garrison Frazier, a Baptist clergymen, aged 67. Born in Granville County, N.C., Frazier had been a slave until just eight years prior, when he bought himself and wife for $1,000 of his own money (over $30,000 today). He’d been in the ministry three and a half decades, and was in failing health. Armed with the delegation’s sentiments, he commenced a colloquy with the Secretary, preserved for history.

The transcript presents us with visceral insight into the minds of Black Americans just three weeks before the 13th Amendment passed Congress. What emerges from the exchange is a sophisticated, clear-eyed understanding on the part of African Americans as to the causes of the war, the policies of the Lincoln Administration, and their own contested status in the republic. As to the purpose of the conflict, Frazier cut to the heart of the matter, in a manner denied (or unknown) by many white Americans to this day.

Stanton: State what is the feeling of the black population of the South toward the Government of the United States; what is the understanding in respect to the present war—its causes and objects—and their disposition to aid either side.

Frazier: I think you will find there are thousands that are willing to make any sacrifice to assist the Government of the United States, while there are also many that are not willing to take up arms. I do not suppose there are a dozen men that are opposed to the Government.

I understand, as to the war, that the South is the aggressor. President Lincoln was elected President by a majority of the United States, which guaranteed him the right of holding the office and exercising that right over the whole United States. The South, without knowing what he would do, rebelled. The war was commenced by the Rebels before he came into office. The object of the war was not at first to give the slaves their freedom, but…to bring the rebellious States back into the Union and their loyalty to the laws of the United States.

Afterward, knowing the value set on the slaves by the Rebels, the President thought that his proclamation would stimulate them to lay down their arms, reduce them to obedience, and help to bring back the Rebel States; and their not doing so has now made the freedom of the slaves a part of the war.

It is my opinion that there is not a man in this city that could be started to help the Rebels one inch, for that would be suicide. There were two black men left with the Rebels because they had taken an active part for the Rebels, and thought something might befall them if they stayed behind; but there is not another man. If the prayers that have gone up for the Union army could be read out, you would not get through them these two weeks.

Then, after inquiring as to their understanding of the Emancipation Proclamation (which they grasped firmly), Stanton made a crucial probe:

Stanton: State what you understand by slavery and the freedom that was to be given by the President's proclamation.

Frazier: Slavery is receiving by irresistible power the work of another man, and not by his consent. The freedom, as I understand it, promised by the proclamation, is taking us from under the yoke of bondage, and placing us where we could reap the fruit of our own labor, take care of ourselves, and assist the Government in maintaining our freedom.

Homing in on the last part of Frazier’s answer, the Secretary pressed further in grappling with the status of the Freedmen after the war:

Stanton: State in what manner you think you can take care of yourselves, and how can you best assist the Government in maintaining your freedom.

Frazier: The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor—that is, by the labor of the women and children and old men; and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare. And to assist the Government, the young men should enlist in the service of the Government, and serve in such manner as they may be wanted…We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.

Faced with unprecedented social upheaval, Blacks gave the Lincoln administration a direct, unambiguous, eminently reasonable proposal: distribute land—specifically, the plantations abandoned by or seized from rebels—to the former slaves so they could work it and serve the National government.

In their desire for property to secure economic independence, African Americans were speaking exactly the language of the free-labor ideology that animated the Republican Party at the time. In fact, it mirrored Jefferson’s vision of a republic of yeoman farmers and small shopkeepers. The Freedmen sought land not as some free lunch, but as a foundation on which they could work hard, build their communities, and render faithful citizenship to the republic. In this, they wished merely to follow in the footsteps of their white counterparts, who’d received land grants and bought property on the cheap at public auction for decades.

During the war, in fact, Congress had begun the process of colonizing the mountain West with the passage of the Homestead Act in 1862. Through this program, white settlers and corporations obtained millions of acres from the government, which it had seized from First Nations—the same way whites had been deeded lands in the southeast and Great Lakes regions of the country. Including Black Americans in that process would be in keeping with the government’s long-standing redistributionist policies.

Lincoln’s administration had already been experimenting with this approach, in fact. On the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, the government had broken up dozens of plantations and dispersed them to the former slaves, lands their white masters had abandoned in November 1861 after the U.S. Army and Navy liberated the region. With the assistance of federal officials, and hundreds of civilian volunteers from the North, the newly emancipated planted crops, established schools, and built whole towns literally on the ruins of slavery. The Port Royal Experiment was a resounding success, and formed the basis for Sherman, after meeting with the Black delegation in Savannah, to issue Special Field Orders, No. 15.

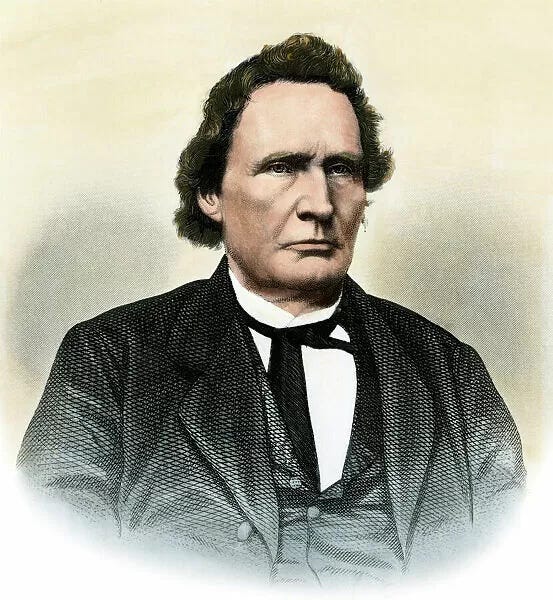

This set of military commands appropriated some 400,000 acres of rebel land along the Atlantic seaboard in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina and divided them into forty-acre plots. Tens of thousands of Black families were settled on these properties, with mules from Sherman’s army thrown in to boot. Following these developments from Washington, Thaddeus Stevens—the radical leader of the House Republicans—proposed an amendment to the Freedmen’s Bureau bill in the fall of 1865. It envisioned creating an executive department mechanism to seize all Confederate estates over two hundred acres—which constituted roughly 2 percent of white Southern families—and to partition that land into forty-acre farmsteads. He explained the justice of such reparations in ringing rhetoric:

Nothing is so likely to make a man a good citizen as to make him a freeholder. Nothing will so multiply the production of the South as to divide it into small farms. Nothing will make men so industrious and moral as to let them feel that they are above want and are the owners of the soil which they till…No people will ever be republican in spirit and practice where a few own immense manors and the masses are landless. Small and independent landholders are the support and guardians of republican liberty.

Abraham Lincoln did not share Stevens’s views on land redistribution, at least then. He may have gotten there; in his final speech, he endorsed limited voting rights for Blacks, a position he’d not previously held. Lincoln had pushed the country left in the years before the war, and continued to move in the radical direction as the conflict unfolded. During that very speech, in fact, he had Charles Sumner, the leading radical in the Senate, stand beside him at the White House window. But John Wilkes Booth heard the speech, too, and the promise of Black citizenship drove him mad. His bullet forever rendered Lincoln’s Reconstruction policies a historical enigma.

A month before he died, however, the President spoke to the moral question of slavery during his Second Inaugural Address. There, he identified—in uncharacteristically graphic prose—the twin injustices of bondage:

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said 'the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.'

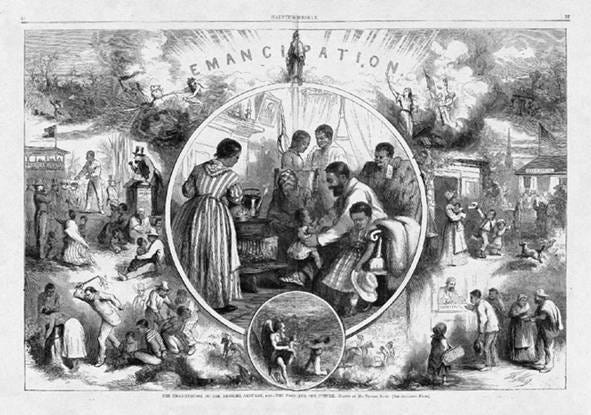

Violence and theft. That, to Lincoln, was the core crime of slavery. In his strident attacks on the institution in the 1850s and ‘60s, he emphasized the wrong of slavery in terms of stolen labor. He returned to that theme in the Second Inaugural, noting that it seemed “strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces.” Shockingly, he told his audience that God would will the war to continue until the country paid back its former slaves both the blood and treasure it had sucked from them. With the sacrifice of some 400,000 Union soldiers and sailors—Black and white—America satisfied its debt of blood. And through its nascent experiment with land reparations, it seemed poised to pay back the wages of sin.

It never happened. After Lincoln’s assassination, Andrew Johnson assumed the Presidency. A bitter racist from Tennessee, he denounced the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist former slaves, in terms that have set the standard for conservative attacks against public assistance ever since. He excoriated the measure as “immense patronage,” claiming, astoundingly, that Congress was helping Black folks in ways it had never done for “our own people.” Having failed to listen to Frazier, the President claimed such largesse would injure the “character” and “prospects” of the Freedmen by implying that they didn’t have to work for a living. He vetoed the measure along with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, saying that granting the rights of citizenship to Blacks somehow discriminated against whites because “the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race.”1

Congress overrode his vetoes, setting up his eventual impeachment. But Stevens’s provision for land redistribution was resoundingly defeated, and Johnson managed to survive his Senate trial and rescind Sherman’s Field Orders. Eventually, almost all the Black families who’d obtained land were driven off, the estates returned to unrepentant traitors. There would be no remuneration for a people emerging from two and a half centuries of bondage. After a brief window of progress, Reconstruction was overthrown in a reign of terror, and the white rebels returned to supremacy in the South. The Supreme Court commenced its evisceration of the legal basis for Black equality shortly thereafter. No sooner were the chains struck from the slaves’ wrists, than the Freedmen were reduced again to a subaltern state. African Americans would make great strides in the decades to come, often accumulating land against the greatest of odds. Yet on the whole, they remained mired in poverty and segregation, subjected to the cruelties of a totalitarian state.

II. A Debt Unpaid

As Eric Foner says, land appropriations alone would not have been a panacea for this white power structure. But the point is, the country never seriously tried. Meanwhile, for the next century, the United States continued to practice affirmative action for whites. During his administration, Woodrow Wilson segregated the federal government (which had been one of the few places to hire Blacks) and the military. Later, as historian Ira Katznelson writes, the New Deal reinforced structural racism in staggering ways, allowing Southern states to set up conditions for Blacks that were “abominable.” African Americans were explicitly carved out of the GI Bill, Social Security, and housing aid by Dixie congressmen, with FDR’s begrudging acquiescence. Blacks benefitted second hand from the legislation, but not nearly in equal measure.

Finally, in the wake of the Second Reconstruction, this official discrimination ended. In an attempt to redress lasting wrongs, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations implemented affirmative action—this time for Black Americans. After a century of delay, the country was taking a small step to atone for the stolen wages of slave labor. Instead of direct economic reparations, though, it endorsed race-conscious admissions practices in universities and workplaces. In other words, a chance at a better job in the future, not back-payment for labors of the past. Inadequate, incommensurate with the historical harm, but a start.

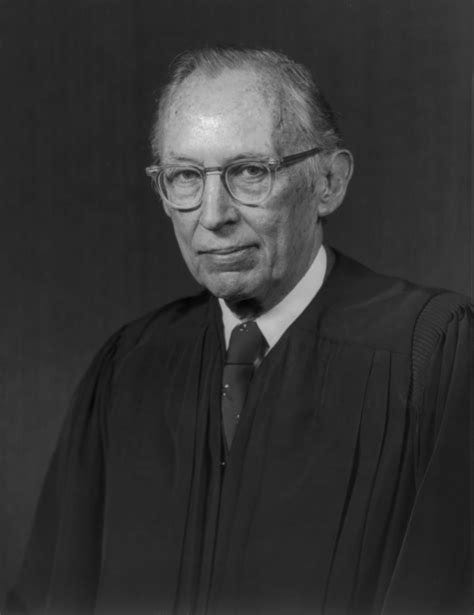

It didn’t last long. Barely a decade into the policy, it was challenged before the Supreme Court. The death of affirmative action began with the Bakke decision of 1978, when a Virginian, Lewis Powell ruled that race-conscious admissions could not be employed as a means of remedying the rape, torture, lynchings, bombings, and theft visited upon Black Americans for generations.

This was despite the fact that laws like the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1870, as well as the Freedmen’s Bureau and other federal agencies, were set up by Congress explicitly to assist African Americans and remediate their suffering. The government had created entire divisions of United States Colored Troops, for God’s sake, without whose valor, Grant said, the Union would’ve lost the war. Likewise, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed by congressmen who specifically talked about it in terms of preventing racism against Blacks. Powell ruled that this didn’t matter, that society can’t rectify injustice against people who’d been enslaved and held as second-class citizens for almost 340 years, because doing so would create “a racial spoil system.”

Instead, he allowed affirmative action as a way of creating “diversity,” which the Court claimed bore benefits to all students. You see the slippage? Instead of upholding it as a means of repaying Black Americans (however indirectly) some of their stolen wealth—and thereby rectifying a national crime—affirmative action was justified by the virtue of campus multiculturalism. And it then applied that vague claim to all manner of students, including those from groups not connected to the original injustice (like students from today’s Africa, or from any non-white country or group).

Pluralism is admirable and good. But it makes for a much weaker, murkier legal rationale than repairing historic degradations against a specific group. It’s baffling that the Court thought diversity—which offers little in the way of sound judicial principle—was somehow more constitutional than, you know, the actual purpose of law, which is to repair harm and render justice. Especially since Congress during Reconstruction so clearly had the Freedmen—and all Black Americans—in mind as they crafted legislation and erected institutions to assist them after the horrors of slavery and the ravages of war. Baffling, but not surprising, coming from the pen of a Southerner.

And now, with yesterday’s foreordained decision, we see the culmination of the classic conservative strategy: first, weaken a progressive program by stripping away its strongest rationale but allowing it to continue on flimsy grounds. Then, watch as the program becomes ineffective, confusing, and unpopular. Finally, attack those very grounds—which conservatives themselves laid down—as untenable, so as to kill the whole damn thing. This despite the fact that both lower courts found that the plaintiffs—after the testimony of 130 witnesses—did not prove a single Asian American applicant to Harvard was discriminated against on account of their race. The conversations some claimed were had about their personalities were uttered equally of all applicants, personality being a legitimate criterion in making a decision. The data in the trial showed, meanwhile, that Asian applicants’ chances under the policy declined by just 0.08%. In fact, the percentage of Asian students at Harvard has been rising steadily for decades.

And even if they were discriminated against, how is that cause for ending a policy aimed at dismantling racism? If anything, it would be further justification for taking active measures to eradicate all racial animus from our institutions. Black applicants were not chosen over Asians—nothing that the plaintiffs entered as evidence proved that cause and effect. If anything, as Justice Sotomayor writes in her dissent, it is white applicants who continue to benefit from preferences and privileges: through athletic scholarships; dean’s list picks; faculty and staff parents; and, most perniciously, legacy admissions. If Asian applicants are being unfairly passed over, it’s likely to the continued benefit of whites.

How the Supreme Court can allow these violations of our fictive meritocracy to go on—while striking down a race-conscious policy it had affirmed in multiple cases over forty years—is unconscionable. Nothing has changed in university admissions during the past two decades that would merit a revision to the policy. As with Dobbs, all that’s changed is the personnel of the Court. Which means we’re governed not by the rule of law, but the whims of men. And the fact that the majority exempts military academies from their decision—for reasons pulled purely out of thin air—just reveals them, once again, to be hacks engaging in their own arbitrary form of social engineering.

As to that personnel, it’s worth recalling that two of the justices in the majority were put on the bench by unconstitutional means. Two of the others have been implicated in ethics violations (not to mention, in the case of Thomas, January 6th) that, if they were sitting on any other court, would’ve had them hauled before a judicial conduct commission and thrown out of office. Instead, they’re allowed to reign with impunity, as the Chief Justice has all but declared the Court beyond any constitutional check or congressional oversight. It is, in other words, above the law—the apotheosis of unlimited government that conservatives claim to oppose. Oh, and did I mention that the man behind the plaintiffs, Edward Blum, is a member of the Federalist society, whose current Board chairman, Leonard Leo, has been the one pairing the justices with billionaire buddies? Easy to win cases when you pick the jurists from your own club, pack them on the bench, and lavish them with the largesse you deny everyone else. Hannibal Hamlin’s aphorism bears repeating:

Of all the despotisms on earth, a judicial despotism is the worst. It is a life estate.

Matt Bruenig, over at

, argues that yesterday’s ruling actually reopens the door to affirmative action’s original premise: redressing discrimination against a historic minority. I hope he’s right. But colleges can walk through that opening only in a discreet, oblique manner now and many will be too afraid or apathetic to try. And the message the decision sends is unmistakable. It tells historically maltreated Americans, once again, that they’re on their own: the government does not care about you or your rights. It further precludes any discussion or attempts to rectify injustice committed as a nation against whole categories of people. It says, in effect, that there’s no such thing as social sin or social justice. As if slavery and Jim Crow were applied to individuals who all happened to be Black.This is the warped, blinkered, morally bankrupt vision of the Roberts Court and his counter-revolutionary movement, one that claims—beyond the most utopian fantasist—that we live in a post-racial paradise. You’ve really got to wonder about a person who would, like John Roberts, make it his career goal to take the legacy of Dr. King and shred it to pieces. In his mind, all that past prejudice is water under the bridge, magically evaporated by the dawn of a new day. Someone might want to point out to him that there are still hundreds of statues dotting the land in honor of men who launched a slaveholders’ rebellion that left a million Americans dead and the republic nearly shattered. That’s not accidental. Tribal hatreds have long afterlives. And slavery did not die honestly. Even after the massive bloodletting of the war, the southern states abolished the institution only at the point of federal bayonets. Same with de jure segregation, which occurred well within living memory.

An honest conservative would acknowledge that cultures are deeply ingrained by thought, custom, and social conformity. Change must be sustained firmly over generations. We’ve made much progress on the race question as a society. But the deep South is still a retrograde region, whose crypto-fascist worldview remains alive and well in too many quarters. I recall watching gobsmacked as the residents of Charleston welcomed the Hunley—a recovered Confederate submarine that contained the remains of its crew—into the harbor. A flotilla of private yachts all bearing the Stars and Bars accompanied the vessel, an amphibious salute that was followed by a parade downtown. Thick crowds cheered along the route, their euphoria palpable. On vacation from New York with my family, my sixteen-year old Yankee brain exploded. This wasn’t 1890 or 1930 or 1960. It was 2000. Four years later, the rebel sailors were given a military burial with full honors.

III. The Weight of the Past

“Fellow-citizens,” said Lincoln, “we cannot escape history.” History shapes the world we live in and the lives we lead. Our forebears hang over us like heavy oaks. No matter when our ancestors arrived in America, we inherit all of its past: its triumphs and its crimes. But if we study history’s currents, we can better navigate its rapids and chart a wise course. Too many refuse, however, and in the Roberts Court they have powerful friends. You may tell me that sizable majorities of Americans oppose affirmative action, not just in the South, but in states like California and Michigan. True. But a large plurality of Americans—48%—still believe that the main cause of the Civil War was states’ rights. Only 38% think it was slavery. Lincoln said in his Second Inaugural that “all knew” slavery was the cause of the war in 1861; they don’t know that today. The Lost Cause endures.

And if people hold false ideas about the war, they know next to nothing about Reconstruction. I came through a good public high-school with a strong history department. Yet Reconstruction was essentially fly-over country in our curriculum, and this was in New York. Corruption and carpetbaggers—that was all I learned. Only through my own reading did I come to appreciate its complexity, and I’m unusually (my wife might say obsessively) curious. Most Americans have neither the time nor the inclination to study the details of land appropriations in the 19th century. Many cling like children to outright nationalist myths. But the snippet of history I’ve recounted here is not some woke CRT propaganda. It’s true. And until we comprehend the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth of our country, our reasoning on this issue will be woefully crude.

The justices on the Supreme Court can’t claim ignorance, though. They know better. But like a zombie in a horror film, the majority is intent on dragging us back to a darkness we’ve barely left, an America that just can’t lay the whip in the grave. Marx said history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. At this point, I’d take the tragedy—at least tragedies end, the bodies buried and the rebuilding begun. Farces like ours go on and on. The fact that the current act is being performed in the name of the 14th Amendment tips it into full-blown absurdism.

In the face of the massive inequalities in this country, affirmative action was always weak tea. It did nothing to dismantle the bastions of elite power, and no education policy can ever close wealth gaps that are economic in origin. I’d prefer we didn’t have an aristocracy in this country (after all, we claim equality as a self-evident truth). Yet as long as we have one, I’d rather it be diverse. In an actual egalitarian nation, we’d have no Ivies, which are just glorified patronage clubs, gatekeepers to society’s most plum posts. My preferred approach would be to make private schools, at every level, public and free (or, short of that, tax the endowments of private schools heavily).

As for admissions, only democratic lotteries would render the process truly fair (arguments can be found in the Atlantic; Equality by Lot; the Atlantic again; NPR; Boston Business Journal; New America; Forbes; and Current Affairs). Beyond that, we must continue the emancipatory spirit of Thaddeus Stevens and level all areas of our society through universal, democratic, class-conscious programs. Until we do, reparations for the descendants of enslaved people (not to mention First Nations) will likely never occur.

Affirmative action was not about diversity. It was about justice. The whole approach to the issue in the United States has, on that score, been shameful. In the wake of the Civil War, the Freedmen didn’t ask for much—just protection of their natural rights, and land to make a fresh start. After a few halting tries, the government gave up and turned them over to the tender mercies of their former masters. This was in the same era that Uncle Sam seized millions of acres from Native Nations in the West and gave them to white settlers, with the Army to keep them safe. A century and half on, America still refuses to pay the families of its former slaves a modicum of the wealth piled by the bondsman’s 250 years of unrequited toil, nor even erect a memorial to their name. Andrew Johnson would be proud.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: HarperCollins, 1988), 247-250.

Heartbreaking...

Well said. Loved the context and history to better understand current policies. Very concise and thoughtful.