I.

Imagine you made a cheap knock-off of The Godfather, swapping out its 1940s New York setting for today’s Montana; the Corelone compound for a sprawling ranch; and fedoras for cowboy hats. Then you stripped it of all profundity, cinematography, and character development, and injected it with an overdose of heavy-handed spartanism. Finally, you fired its cast of astonishing Method actors and hired dim replacements, directing them in such a way as to produce one shoddy, crude, preposterous scene after another, strung together by leaden and hackneyed dialogue. What would you get?

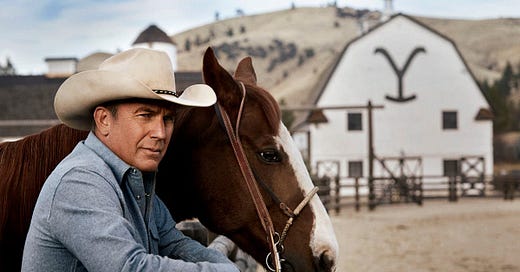

The answer is Yellowstone, the most popular television show in America. The Paramount series (now in its fifth season) notched Kevin Costner a Golden Globe recently for best actor, its first piece of hardware after failing to garner even so much as a nod before. Combined with its snubbing by the Emmys, this awards-circuit rejection has led to complaints of liberal bias against the champion of red America. Such a suspicion would be in keeping with the show’s paranoid worldview. But after enduring its first season, I can vouch that this neglect isn’t because of politics. It’s because Yellowstone is a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad show. The only accolade it should get is the dubious honor of destroying a proud American film genre.

For those lucky souls unfamiliar with the series, Yellowstone follows the Dutton family and their attempts to defend the titular ranch—the largest in the country—from the encroachments of their First Nations neighbors, government agents, and city slickers. The first takes the form of Broken Rock Indian Reservation, led by the proud, calculating Chief Thomas Rainwater (Gil Birmingham). The last is embodied in Dan Jenkins, a shady land tycoon from California played by Danny Huston. To fend of these foes, the widowed John Dutton (Costner) turns to his kin: Jamie (Wes Bentley), the family consigliere; Beth (Kelly Reilly), a caustic, manipulative finance baron and Ivanka look-alike; Kayce (Luke Grimes), a dreamy prodigal son living with his Native wife, Monica, and son on the rez; and Lee (Dave Annable), the eldest and head of ranch security.

John learns that Jenkins is building a subdivision on the adjoining property, which requires damming a shared river for power. Meanwhile, some of his cattle wander onto tribal land, leading the Indians—including Monica’s relatives—to claim ownership. An armed standoff ensues with Lee’s forces, and the Natives give Kayce an ultimatum: our side or your father’s. But there’s not much doubt about his loyalties, since he literally bears on his chest the ranch’s cattle brand, which his father has seared into the flesh of his underlings. Such torture—along with murders, beatings, and other punishments—is meted out by the family’s Luca Brasi: Rip Wheeler (Cole Hauser), the ranch foreman and Beth’s sometime paramour.

Sure enough, Kayce’s date with destiny arrives when John does what any reasonable person would in his shoes: dynamite the river to redirect its course and launch a commando night raid to rescue his bovines. This is despite the fact that a government commission sides with Jamie as he defends the ranch in public hearings. Its head, Lynelle Perry (Wendy Moniz) is the former governor and happens to be sleeping with John. Somehow it doesn’t occur to the rancher to use this immense pull to resolve his disputes. In the course of the invasion—in which cowboys wield assault rifles on ATVs, while Dutton circles above in a chopper—Lee’s killed by Monica’s fiendish brother. But not before Kayce comes out of nowhere and pumps multiple shots into the Indian’s prostrate body, after telling him there’s no heaven. That’s episode one.

Yellowstone is the passion project of Taylor Sheridan, a small-time actor turned writer who’s himself a skilled horseman. Unlike Kayce, his cowboy identity is one of choice, though, not blood: as Sridhar Pappu writes in The Atlantic, he grew up in Fort Worth, the son of a cardiologist. His family had a ranch in the country, which he visited on weekends. After finding modest success on shows like Sons of Anarchy, he turned to screenwriting, first with the movie Sicario (2015) and then the neo-Western Hell or High Water (2016). The latter was a critical and commercial success (rightfully so) and earned him coveted creative license. He poured that freedom into Yellowstone, which has generated two prequel spin-offs, 1883 (2021) and 1923 (2022). Along the way, he’s made a prison drama (Mayor of Kingstown) and an actual mafia series, Tulsa King (2022).

This gonzo success is all the more gobsmacking given the quality of the flagship show. It’s hard to overstate just how awful Yellowstone is on aesthetic and historical levels. The writing’s atrocious, the characters cardboard, the “themes” amounting to fascism American style: the world is a vicious Hobbesian/Darwinian state of nature, with blood-and-soil tribes locked in warfare over scarce resources. In such a milieu, real men ride horses, fuck hard, and shoot harder, dispensing vigilantism without a second thought.

Cities, by contrast, are black holes of soft, drug-addled liberals crowding on the God-given property of rugged Anglo Americans. Indians were terribly wronged once upon a time (by someone, actual blame is never assigned) but now they’re equally conniving and hell-bent on taking back the land via hardball politics and open firefights. The gender dynamics, meanwhile, are so toxic as to induce laughs, were it not for the homophobia and constant fear of emasculation on display. The sexual anxieties that overlay the proceedings are at once pathetic and scary.

Sheridan’s created a bizarre alternative reality ruled by fatalism and primitive machismo, where cowboys are turned into capos and attack anyone who might threaten their private Valhalla. The notion of subtler tactics, let alone cooperation, never crosses any character’s mind. Certainly not that of the patriarchal Dutton, who demands absolute loyalty from his family—sound like a certain former President? The show’s a hard-right fever dream in which its stoic heroes can hardly get through the day without encountering meth labs, sex traffickers, car wrecks, and the dread liberal transplants. The only solution to this chaos is to stand your ground, pull your gun, and blast away—calling the cops or even an ambulance is deemed impractical. Is Sheridan on meth?

II.

The prequel, 1883, makes you really think he is. In this spin-off—even worse than Yellowstone—we see the mythic origins of the Dutton family's claim to their land: a brutal wagon train across the prairie led by Civil War veterans—one Confederate, one Union, with a laconic, token Black thrown in for kicks. We meet the first of this trio, James Dutton (Tim McGraw), as he lashes a team of horses to escape bandits. The second, Shea Brennan (Sam Elliott), is a widower and Pinkerton agent now who watches from a distance as Dutton miraculously steers his animals with one arm and shoots his foes down with the other. Based on this impeccable marksmanship and bodily verve, Brennan offers to team up with Dutton in guiding an exodus of hapless German immigrants from Texas to Oregon.

The latter eventually accepts, but not before gunning down a pickpocket on the Fort Worth street in broad daylight and fending off his daughter’s would-be rapist. Just a normal day in the West. Meanwhile, Brennan rips the migrants a new one for not having guns or proper gear, then culls their numbers after detecting smallpox on the body of one confused man. Once the cavalcade commences, it meets with repeated disasters, endured by brute suffering and firepower. This epic journey’s narrated by Dutton’s daughter, Elsa (Isabel May), with lines that challenge the musical Les Miserables in their bathos. Despite the punishing environment, the girl takes a German lover (who’s then killed by marauders) followed by a Native one (whose people are backed into a tragic war with the pioneers).

The series opens with a shot of Elsa looking on in horror as Indians scalp and butcher a white family, stagecoach aflame, before she shoots down a brave. The only thing more insane than the bastardized Romeo & Juliet trope is the fact that three Civil War veterans, one of whom’s Black, guide a wagon team for months without that titanic conflict (let alone slavery) ever arising. In fact, during a flashback, we see Dutton coming to his senses on the Antietam battlefield, the bodies of his rebel soldiers strewn around him. Mortified, he takes consolation in the embrace of a Union general (a stiffly whiskered Tom Hanks) who caresses him as he weeps. Sheridan, incredibly, has managed to shoehorn Lost Cause propaganda into a major TV series in 2021.

This unconscionable choice is outdone only by his portrayal of how the Duttons got their ranch. James and the stricken Elsa wander into the paradisal valley, which lies conveniently vacant and pristine. After an interminable death scene in which we’re treated to more ersatz poetry, she expires, imbuing the land with her pure American spirit. That’s why, in Yellowstone, Dutton’s descendants are justified in their unapologetic defense of their property: they weren’t responsible for removing the Indians. Their noble ancestor (somehow not a racist, despite being a Dixie officer) was in essence bequeathed it by the Creator via his Native-enraptured Aryan maiden.

You don’t need a doctorate in history to know that every piece of this story’s absurd. Wagon trains to Oregon? Those crossed the landscape in the 1840s and ‘50s, all but disappearing after the government completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869 (fifteen years before the events of the show). Such caravans, while facing hardships, were peaceful affairs for the most part. Indians merely taxed the migrants for crossing their land, when they weren’t outright assisting them. Contra Sheridan, the settlers brought along many luxury goods, with chucked dressers, bathtubs, and even pianos littering the trail. The greatest risk was drowning.

Immigrants? Germans came to the United States before the Civil War, not after, settling in the Great Lakes and Midlands. Immigrants in the Gilded Age hailed from southern and eastern Europe, most making their home in the cities along the Atlantic seaboard. Migrants West came by rail to work the mines and live in company towns (not on wagon trains) or purchased land from Uncle Sam (redistributed from the Indians). And the notion that a European in 1883 wouldn't be immunized against smallpox—or even know about it—is improbable. As Derek Thompson writes recently in The Atlantic, the vaccine for the disease was developed in 1796. Within ten years, it had gone global, especially in Europe where the state promoted its use.

Finally, a word about all this bloodshed. Was the 19th-century West a violent place? Sure, though less than today. Violence came mostly in three modes: First, the wars of the Army against the First Nations, the longest in our history. Second, racial pogroms by whites against Chinese immigrants and other minorities. Third, attacks on organized labor by soldiers and Pinkerton agents. Shea Brennan, Elliott’s character, would’ve been employed by a railroad to bust the skulls of striking miners, not lead a wagon train of boot-strapping pioneers. Western towns experienced occasional vigilante lynchings in their early days, and feuds. But those practices were quickly superseded by organized courts and the rule of law. Sheridan’s image of anarchy is perverse wish fulfillment.

And yet he and his collaborators would have you believe that a wagon train—populated by ignorant, diseased, clueless immigrants—was still crossing the West in 1883, just a few years before the Army's final massacre of the First Nations at Wounded Knee and the closing of the frontier by the government. It’s one thing to embellish the truth for dramatic purposes. It’s another to ride roughshod over it in the service of baleful brainwashing.

III.

Ok, you might argue, but isn’t Sheridan simply regurgitating the tropes of the Western? The cowboy movies of the 1930s and ‘40s and ‘50s were grossly inaccurate, but who cares? Does anyone believe Stagecoach (1939) is a realistic depiction of the West? You have a point. The West that’s come to us through popular culture was an invention of entertainers and showmen: first Buffalo Bill Cody, then novelists, and finally Hollywood. I can’t ding Yellowstone and 1883 for perpetuating this myth if I don’t also attack those pictures, right?

Not exactly. The Westerns of the Golden Age of Hollywood were politically and historically incorrect, yes. But as stories, they formed the bedrock of one of the archetypal American genres. The prototype comes from James Fenimore Cooper, the country’s first novelist and scion to the founding family of my hometown. In books like The Pioneers (1823), The Last of the Mohicans (1826), and The Prairie (1827), Cooper invented his hero Natty Bumppo, who rejects white society after being raised by Delaware Indians. Bumppo’s a crack shot who lives in the woods and harbors deep suspicions of “civilization,” establishing the self-reliant traits that later typified cowboys. Hollywood refined the genre into eight main conventions:

Conventions of the Western

The focus of the Western is on the frontier, freedom, and men on horses.

The dramatic space is divided between the town and the wilderness. Violence flares when outlaws arrive from the wild.

The wilderness has two representatives: the cowboy and the outlaw.

The town has three representatives: the sheriff, the good woman, and the bad woman.

Violence is expected.

There are tests of manhood, usually violent.

Indians are bloodthirsty, except those who have been tamed.

“Moving on” is the theme. Traditionally, Westerns depend on moving against the landscape. The cowboy restores justice to the town, but can’t share in the new community—he’s a loner, and must depart.

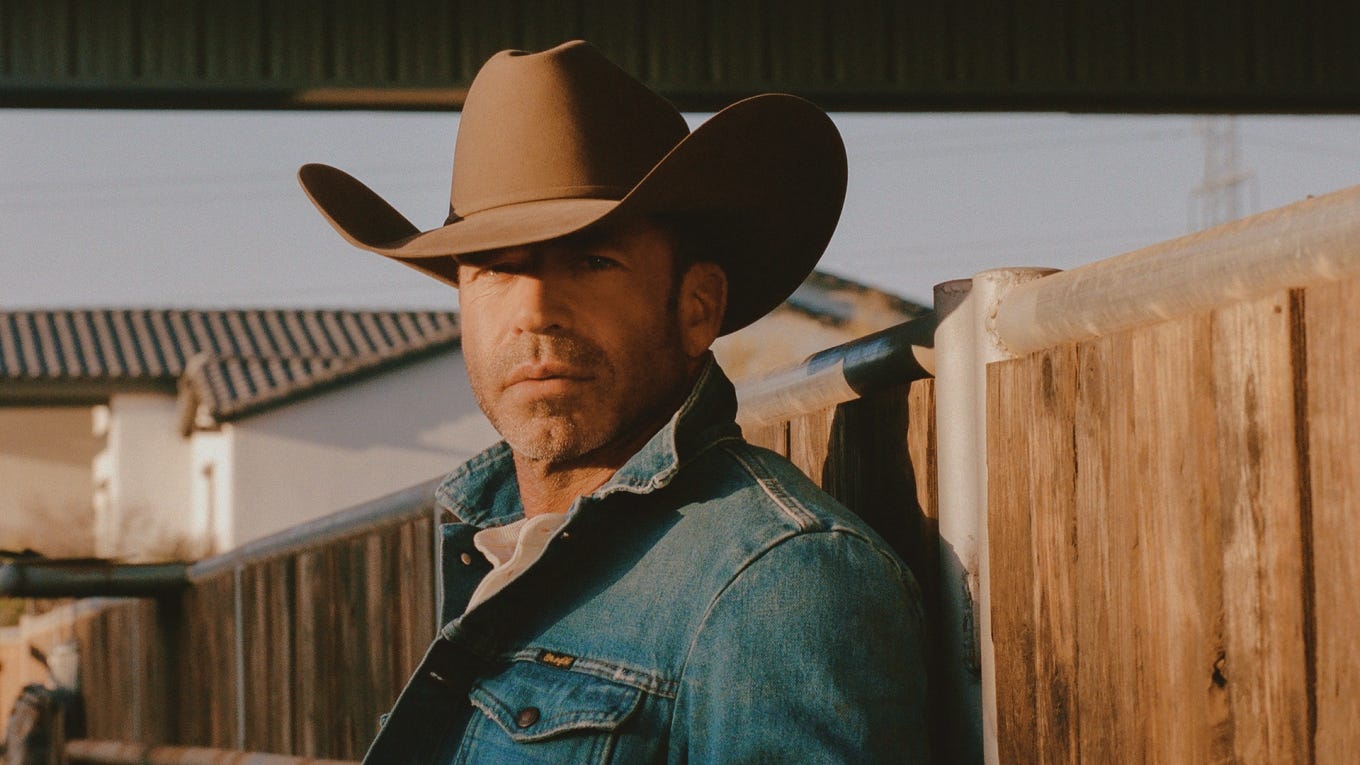

When done well, these conventions yielded classics such as Howard Hawks’s Red River from 1948, with John Wayne and Montgomery Clift as opposing leaders of a cattle drive. The key motif in the Western is the relationship between the individual and the community. Typically, the cowboy helps save the town from the outlaws, but as a solitary figure tied to nature, he can’t share in the restoration of the social order. Instead, he rides off into the sunset, his lot forever bittersweet. In other words, even as it distorts history (not least with its racism), the Western guides us into deeper truths. High Noon (1952), for example, is a parable of the McCarthy Era, chronicling how the community fails to stand up to the wicked in defense of the persecuted. My late friend and editor Kevin Courrier expounded on this theme in a review from a few years ago:

The mythic loner of the Western has always reflected that split in the psyche of the American character where the hopes of nationhood are continually set against the rights of the individual…Unlike the gangster figure of the Depression Era who chose to live outside the law…the hero of the Western always sought Americanism, and permanent roots, even though, deep down, he knew he'd never have them.

The contrast he draws between the gangster and the cowboy is instructive. The latter’s a figure of the modern, frenzied cityscape. Unlike the cowboy, he seeks not to save society, but war against it. As such, he represents our sociopathic side, the underbelly of the American dream. Scarface, Michael Corleone, Tony Soprano—these characters wish to dominate and control all in their path, knowing that their position at the top depends on ruthlessness. The great film critic Robert Warshow compared the two characters in his famous essay from 1954:

Where the Westerner imposes himself by the appearance of unshakeable control, the gangster’s pre-eminence lies in the suggestion that he may at any moment lose control; his strength is not in being able to shoot faster or straighter than others, but in being more willing to shoot. ‘Do it first,’ says Scarface expounding his mode of operation, ‘and keep on doing it!’ With the Westerner, it is a crucial point of honor not to ‘do it first’; his gun remains in its holster until the moment of combat.

This is why Sheridan’s attempt to recast cowboys as gangsters in Yellowstone is a fool’s errand. Filmmakers often mix genres together in movies, to great success. But the gangster and the cowboy are like oil and water. In their attributes, settings, and relational dynamics, they make for polar opposites. For example, the gangster—ever fearful of getting whacked—surrounds himself with his crew. He needs people in his life, even as he destroys them in his business.

The cowboy, on the other hand, is a man of repose and solitude. “His loneliness,” writes Warshow, “is organic, not imposed on him by his situation but belonging to him intimately and testifying to his completeness.” But though the cowboy is anomic, “it is obviously absurd to speak of him as ‘anti-social,’ not only because we do not see him acting as a criminal, but more fundamentally because we do not see his milieu as a community.” The Westerner is also “par excellence a man of leisure,” Warshow continues:

Even when he wears the badge of a marshal or, more rarely owns a ranch, he appears to be unemployed…As a rule we do not even know where he sleeps at night and don’t think of asking…Possessions too are irrelevant. Occasionally, employment lies open to him, but when he accepts it, it is not because he needs to make a living, much less from any idea of ‘getting ahead.’ Where could he want to ‘get ahead’ to? By the time we see him, he is already ‘there’: he can ride a horse faultlessly, keep his countenance in the face of death, and draw his gun a little faster and shoot it a little straighter than anyone he is likely to meet.

The gangster, for his part, strives to get ahead at every turn. He’s a capitalist with a Tommy gun. “The World Is Yours,” reads the neon sign in Scarface (1932), and its anti-hero wants to eat that world. Fast cars, fast women, fast everything—the gangster lives for the material pleasures of his ill-gotten gains, which, in the end, form his prison. To have the cowboy owning a mega-ranch, then, and guarding his turf like a kingpin is to destroy the physical and spiritual freedom he represents. It turns him into the cattleman, the corporation, which the cowboy always hated. The cowboys in Yellowstone have more money than God and more perks than a country club. Where’s the pride in that?

Finally, the killing. The gangster and the cowboy exercise a hold on our imaginations because they offer competing responses to the problem of violence. As Warshow puts it, the gangster allows us to taste the thrill of being a professional people hurter, while also punishing that same desire. In his loss of control, he represents our Id, which both attracts us with its erotic physicality and repels us in its mayhem. When Cagney smushes a grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s face in The Public Enemy (1931), its cruelty disgusts us. This is a key difference from the Western, as Warshow notes:

There is little cruelty in Western movies, and little sentimentality; our eyes are not focused on the sufferings of the defeated but on the deportment of the hero. Really, it is not violence at all which is the ‘point’ of the Western movie, but a certain image of a man, a style, which expresses itself most clearly in violence…A hero is one who looks like a hero.

It’s the perversion of this heroic style that makes Yellowstone and its siblings so loathsome. Cruelty saturates these shows, with nearly every character taking part. In Sheridan’s eyes, this is legitimate. Brando’s Don Vito dispatches enemies fiercely, but the tone of The Godfather (1972) is against his murderous deeds. Coppola sought to explore the wages of sin, while never excusing it.

This is a point lost on Sheridan. He claims that he weighs the cost of violence, but his approving tone—and his prurient indulgence in the Duttons’ vice—speaks otherwise. The moral and emotional fallout of their choices is never processed, unless you count a few manly sniffles from Costner. But the people they take out are degenerates anyway, so why shed a tear? Better rid the world of their contagion than let an Edenic ranch be desecrated by the impure.

Nothing could be further from the values of the classic Western, as Warshow tells us:

Those values are the image of a single man who wears a gun on his thigh. The gun tells us that he lives in a world of violence, even that he “believes in violence.” But the drama is one of self-restraint: the moment of violence must come in its own time and according to its own special laws, or else it is valueless.

The lack of restraint, in the end, is the ultimate sin of Yellowstone. When the cowboy is the first to draw—and draws over and over when he doesn’t need to, leaving a trail of carnage in his wake—he becomes irredeemable. He loses his nobility, his value, his style. If the answer is that you’re turning him into a gangster on purpose, one must ask why you’d want to, when the other genre is ready-made for that character.

Moreover, the lack of restraint kills drama. Narratives work by creating tension and then releasing it, like a pop song. Chekhov famously said that if you show a gun onstage in the first act, it better go off by the third. He didn’t say, “Shooting off ten guns and a cannon every five minutes is even better.” This basic lesson fails to register in Sheridan’s mind. When the body count approaches twenty within the first half-hour of the opening episode (as it does in 1883) or a character can’t take a step without running into human wreckage, all dramatic tension evaporates—and our interest with it. At that point, the eyes of any self-respecting viewer glaze over.1

IV.

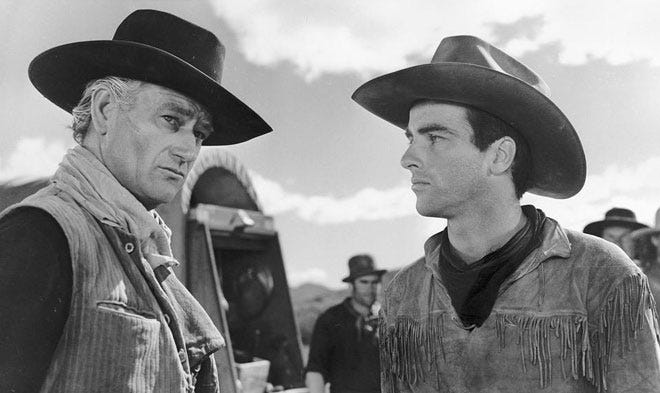

The defense that Sheridan’s creating anti-heroes and upending the genre by design doesn’t exonerate him. Hollywood started doing that in the ‘60s, often with aplomb. Films like The Wild Bunch (1969) and McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) are unconventional Westerns and masterpieces of American cinema. More recent installments have met with success, too. I'm thinking of films like No Country For Old Men (2007) by the Coen brothers (which mixes in elements of the psycho killer genre), and their remake of True Grit (2010). Likewise, the 2015 picture Slow West with Michael Fassbender. The Mustang (2019) and Buck, a documentary from 2011, are beautiful tales of how horsemanship heals the wounded soul.

These films work by playing with our attraction to violence, subverting our expectations of justice, and drawing characters we care about. When they die, their deaths shake us. The directors do all this while putting their own gloss on the style, values, and self-restraint of the classics. Take The Wild Bunch, directed by Sam Peckinpah. Its central idea is that William Holden’s Pike Bishop and his band of robbers are, ironically, the true men of honor—the lawmen on their tracks lack all conviction. It's this ethic that marks the Bunch as relics in the modern age, eclipsed by machines and bureaucrats. Warshow highlights the critical role of honor for the cowboy:

What does the Westerner fight for? We know he is on the side of justice and order, and of course it can be said he fights for these things. But such broad aims never correspond exactly to his real motives; they only offer him his opportunity…What he defends, at bottom, is the purity of his own image—in fact his honor…The Westerner is the last gentleman, and the movies which over and over again tell his story are probably the last art form in which the concept of honor retains its strength…The Westerner is there to tell us that even in killing or being killed, we are not freed from the necessity of establishing satisfactory modes of behavior.

Warshow concludes by observing that if talented artists don’t explore violence, like Peckinpah, the task will be “left more and more to the irresponsible.” Sheridan established such satisfactory modes in Hell or High Water. But whatever creative juices he had going in that picture have abandoned him with Yellowstone. He has no editorial oversight on set, writing scenes often days or even hours before filming. This lack of collaboration or even basic research yields doltish, dangerous results. In channeling his most sadistic impulses right to screen, he’s abdicated all responsibility. His cowboys have no honor, and neither does he.

As culture, as politics, as history, Yellowstone is shameful. And yet, as mentioned, it’s the most popular show in the country. Given its dreadful nature—and how it mainlines myths like heroin—this doesn’t reflect well on Americans. The corrupt version of the Western (which Clint Eastwood is most to blame for) has become an ideological badge for many, buttressing the nation’s reactionary turn since Reagan. The predatory, dog-eat-dog values the show endorses do real damage, breeding a cynical, false view of human nature and numbness to moral evil. The New York Times held a focus group with a few fans recently, and their responses are stupefying. Take Kathy, a 56-year old white social worker from Minnesota and an independent:

[The Duttons] are a little rough, but yeah, I see them as good, for some reason. Because I like that John wants to keep his land. He’s fighting for what he truly believes in and believes that he can keep it if he tries hard enough.

Or Charmaine, a 40-year old Black libertarian from Maryland:

I see them as being good. I just see them as a family that, if someone comes up against them, then you kind of see the bad side.

Wouldn’t want to be their neighbors. Have our spiritual and aesthetic sensibilities really sunk so low? How do you account for such callous indifference to barbarism? What’s most sad is that they don’t see how—for all its caviling about corporate America—Yellowstone represents the apotheosis of everything it claims to hate. It’s the cowboy as commodity, a lifestyle aesthetic no less curated than that of a Silicon Valley tech bro. Sheridan’s branding his audience the way Dutton does his kin. The “Taylor-verse” has recouped him with unprecedented power and revenue, as Paramount’s milked Yellowstone into a lucrative franchise. Using Costner and Tim McGraw and Harrison Ford is all part of this strategy, drawing heat from their country music and action movie stardom. (They certainly weren’t cast for their acting, unless you harbor an interest in plywood.) As marketing, it’s brilliant. As art, it’s shit.

One thing’s for sure: Yellowstone captures the mood of contemporary Montana to a T, evidenced by its recent transition from maverick purple to nationalist red. Today, it’s ranchers like Dutton who quash everyday citizens from exercising their rights to enjoy our shared landscapes. With this kind of Dark Ages mentality holding sway over the American soul, what hope do we have for a more egalitarian, cooperative country? The tension between community and the self that typified the classic Western has returned with a vengeance in recent years, as Courrier concludes:

Americans will always define themselves in terms much larger than any one person, but it's individual rights—what the loner represents—that will always run counter and prevail alongside the dream of nationhood…It's a contradiction that has no resolution and the movies have reflected that unresolved riddle endlessly in Westerns.

Maybe not. Maybe there can be a resolution, and in the favor of community. It starts by rejecting the lies of Sheridan and redeeming the cowboy from his grip. “This is America,” John Dutton grunts at one point. “We don't share land here.” Really? The name of his fucking ranch comes from a national park just down the road, part of an immense commons that belongs to us all. If we can restore such solidarity, there might be hope for us yet. At the end of The Wild Bunch, the greatest Western ever made, Pike and the Bunch choose to fight for Angel, their captured comrade, rather than skip town with their payout. They reject the selfish gene, the “You get yours” mindset, and sacrifice themselves for their brother and his people. “This land was made for you and me,” sings Guthrie. Dutton could learn a thing or two.

This isn't the complaint of a coastal liberal shitting on red America, by the way. For seven seasons, liberals flocked to watch Game of Thrones, a show I also found deplorable. I couldn't get through three episodes of that series what with the gratuitous violence, exploitative sexuality, and all around debasement of every character to the film's Machiavellian worldview. And that was just in a few episodes! Like Yellowstone, Game of Thrones takes a noble genre—in this case, the epic—and evacuates it of any enlightening motifs, themes, or redemptive features. It’s like a bastardized Lord of the Rings, nose candy for its sycophantic fans. At the same time, I loved the football drama Friday Night Lights that ran on NBC in the early 2000s. That's a show that brought us into the world of a conservative Texas town by humanizing its members and showing their common struggles and triumphs and pathos.

![The Wild Bunch | film by Peckinpah [1969] | Britannica The Wild Bunch | film by Peckinpah [1969] | Britannica](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HHd2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc44048d9-5dc9-4ef0-a7fc-f222dcc71d75_1600x900.jpeg)

Well I have to watch a few episodes now and see what I think. I do think tv is distraction and entertainment. I am not sure many people are looking for historical accuracy. Now I have to go watch….