American Nations: Part II

E Pluribus Unum: 1750-1815

[This post is Part II of a series. Here are links for Part I; III; IV; V; VI; VII; and the Epilogue.]

I. The Past is Prologue

“The past is the present, isn’t it? It’s the future, too.” Eugene O’Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night

On Sunday, The New York Times ran an article that reflected on the recent rulings by the Supreme Court. It opens by observing that America is drifting apart “into separate nations,” each with diametrically opposed social, environmental, and health policies. “Call these the Disunited States,” it said. For backup, it quotes Civil War historian David Blight of Yale:

[The Court] has produced this Balkanized house divided, and we’re only beginning to see how bad that will be.

America is indeed Balkanized. But the truth, as I outlined in my last post, is that this has been the case from the beginning. The Times divides the new nations into two—the Northeast and Pacific Coast in one corner, the Southeast and Mountain West in the other, with “islands” of liberalism in Illinois and Colorado. Yet as Colin Woodard argues in American Nations, inside these two blocs live smaller ethno-nations with unique ideologies that derive from their first founders. The history of the United States, then, is the history of how these many nations have struggled for power and influence over time—a contest that’s always been with us, and always will. What follows is the first part of that story, which I take both from Woodard and from additional reading.

I. The First American Civil War (1755-1764)

By 1750, the seven Euro-American nations of New France; Yankeedom; New Netherland; the Midlands; Tidewater; Greater Appalachia; and the Deep South were self-sustaining societies, with El Norte in northern Mexico and First Nation on the border with all eight. It was the lands of First Nation that sparked the subsequent sixty years of war. The French, Spanish, Dutch, and British nations were settler-colonial projects sponsored by their respective empires. While loosely connected to the imperial metropoles across the Atlantic, they understood themselves as autonomous nations and functioned as such. And several of them—especially Yankeedom, Greater Appalachia, and Deep South—wanted to expand.

The Yankees believed in Manifest Destiny, a divine duty to spread their utopian project of Christian civilization to the west. The Deep South, meanwhile, had a similar growth mindset. Its harsh slave system of agriculture exhausted the soil and wrecked the environment, requiring ever new lands for cultivation. Meanwhile, poor whites in Greater Appalachia simply wanted to escape the encumbrances of the coastal aristocrats and Yankee missionaries by homesteading further west. Tidewater elites, watching this, saw a fortune to be made in real estate speculation—if they could secure title to lands across the Appalachians, they could fleece the settlers pouring over the mountains. As for the Dutch nation, well, New Netherland’s always been too obsessed with commerce to care. And the Midlands, with its multicultural, pacifist ethos, was never interested in militant expansion.

The one group standing in the way was First Nation. Though depleted by centuries of trauma, it still exercised fierce power. And it was backed by Protestant England’s ancient enemy: France. New France offered a different model of North American imperialism—a hybrid nation that married French customs with aboriginal ways, resulting in a respectful alliance that preserved indigenous culture and enhanced its political agency. At least in comparison to the English approach: segregation/conversion (Yankeedom) or removal/extermination (Deep South).

The British Crown wasn’t opposed to another war with France, but neither was it itching for a fight. The conflagration was lit by an unlikely actor—a Tidewater gent and frustrated colonial officer named George Washington. Washington was a rampant land speculator; his family (like other Tidewater elites) had a financial stake in seeing the Indians displaced so as to facilitate the real estate ventures of their Ohio Company of Virginia. If only he could get Mother England into a brawl with their French protectors. But how? On May 28, 1754, Major Washington’s band of fifty-two men ambushed a smaller force of New French near Fort Duquesne (present day Pittsburgh.) They killed several Canadiens before strategically withdrawing. News of the skirmish reached Europe, and a world war began. It was also the first civil war between the American Nations.

For the next decade, France and Britain—with their respective First Nation allies—traded blows up and down the continent and around the globe. The plucky, outnumbered French scored stunning victories early on at places like Fort William Henry on Lake George (immortalized in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans). But eventually, the British gained the upper hand and defeated their rival at the epic Battle of Quebec on the Plains of Abraham. France ceded its North American territories and left First Nation to the tender mercies of its conquerors. The Euro-American nations prepared to invade west, and Washington could practically taste the money.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the bank. Exhausted from global conflict, its treasury depleted, the British Crown announced a new imperial policy. First, its Proclamation of 1763 banned settlement by the coastal nations on Indian lands. Second, it agreed in the Treaty of 1763 to safeguard the cultural integrity of New France. This included freedom of religion for its Catholic habitants, who would not be expelled or forced to convert. Finally, it announced a series of taxes on the American Nations to resolve its debt crisis. With these measures, officials in London sought to establish peace and prosperity in the empire—consolidate their gains and exercise rational rule over the raucous American Nations. To wit, they dispatched new governors appointed by the Crown to tie the colonies closer to home.

To the Brits, these policies seemed reasonable and prudent. After all, the colonies were taxed much less than subjects in England. But they shocked the Americans—especially Tidewater, Yankeedom, and Greater Appalachia. After a decade of war in which they’d done the lion’s share of fighting and bleeding—all for the purpose of accessing the west—the Crown wished to block their path? Protect their Canadian Catholic foes? And, worst of all, impose a uniform form of government onto their diverse ways of life? Their founders had fled England to get away from that. Now, the motherland was trying to squash self-government. Washington and his ambitious friends were irate. Their plan: do to the Brits what they’d just done to the French.

II. The Second American Civil War (1775-1783)

We all know what followed. Or do we? In our national narrative, the American Revolution was the uprising of humble Patriots against tyrannical Redcoats to secure liberty. The 1619 Project flipped the script, insisting that Americans revolted in large part to protect slavery from British abolitionists. They’re both myths, and they’re both wrong. As Woodard explains, the War of Independence wasn’t a revolution of "America" against Britain. Rather, it was six separate wars of colonial liberation in which the American nations formed a temporary military alliance to achieve home rule.

Or, more to the point, three wars. In truth, only Yankeedom, Tidewater, and Greater Appalachia really fought to break away from Britain. New Netherland and the Midlands were hotbeds of loyalism and didn’t support rebellion. The Deep South, for its part, was coy, seeking whatever arrangement would best maintain its slave regime. The nations formed a military alliance to fight their common foe, but the conflict quickly descended into multiple civil wars and partisan violence. Meanwhile, First Nation sided with the British (as did thousands of enslaved Africans), knowing that the removal of imperial protection would spell its doom.

How, then, did the elites of Tidewater, Yankeedom, and New Netherland convince everyday folks—especially in Greater Appalachia—to risk their lives in a war with Britain? Short answer: they didn’t. The Revolution’s spirit came from an unlikely character—a destitute widower from England named Thomas Paine. Today, Paine is the forgotten founding father. Even his grave is lost. But at the time, he was the single most important figure in the land. His pamphlets were like the blog posts of the day—the first mass media experience in the colonies, one that captured the imagination of a continent. To this day, Common Sense remains the most popular piece of political literature in American history.

It was Paine who turned a civil war between elites into a revolution for equality. As folks heard his clarion call for a republic read aloud in taverns and churches, they sensed a new epoch at hand—a chance not just to throw off a monarch, but to create a free people who could govern themselves, without bosses, aristocrats, or clerics. It was this leveling impulse that drove most of the foot soldiers into the ranks, and that boosted the move for abolition. During the war and right after the peace, these everyday people created state legislatures far more democratic than before—unicameral chambers with short terms of office, subject to recall elections and explicit instructions from constituents.

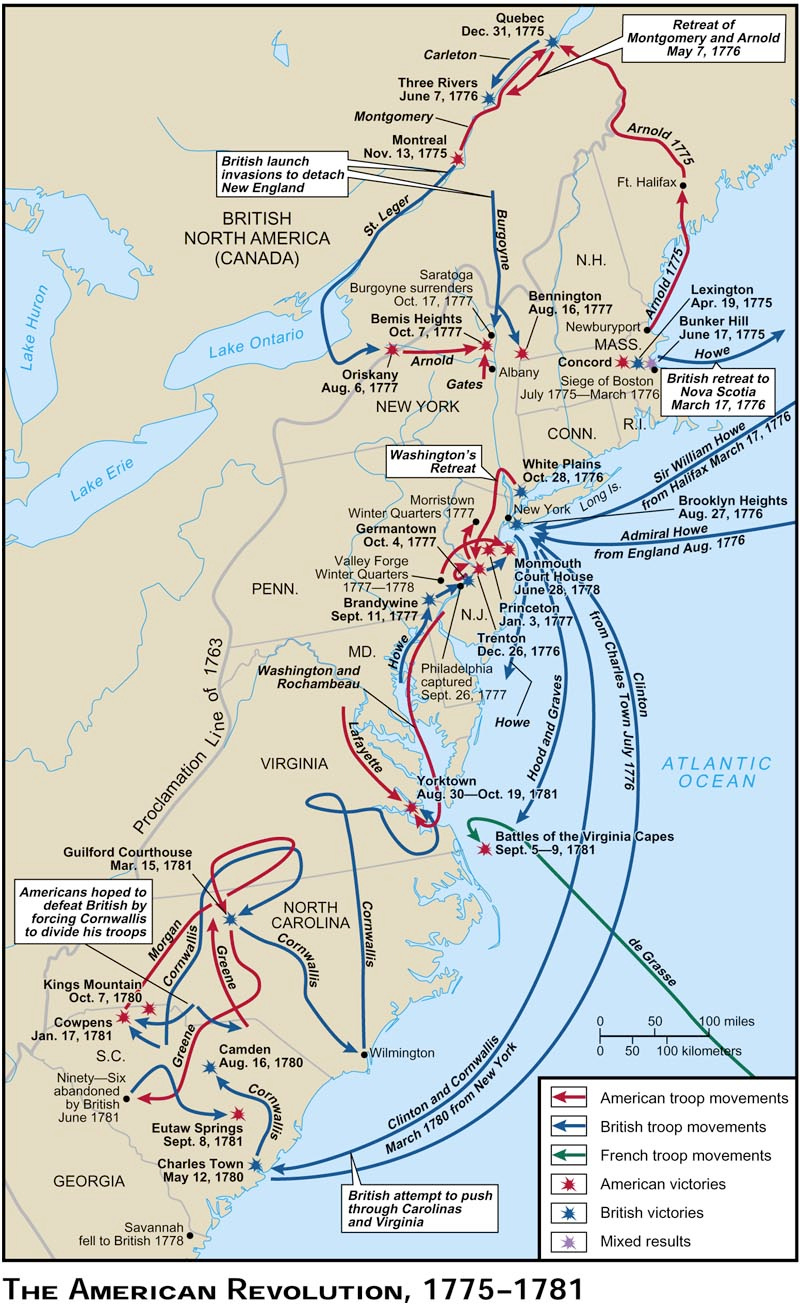

The conflict had several phases, each marking an independent sub-war. In phase one, Yankeedom, led by Benedict Arnold, tried to pull off the conquest of Catholic New France they’d always wanted. Their plans came to grief at Quebec City. But once they succeeded in driving the British from Boston in April, 1776, its nation was independent for all intents and purposes.

Phase two shifted to the mid-Atlantic colonies. The Redcoats returned by occupying New Netherland—a welcome development on the part of the locals, who didn’t want to secede. The nation became riven by guerrilla violence as loyalist families were attacked by Patriots in retaliation. Midlanders, too, sought refuge with the British—including Benjamin Franklin’s own son, the Governor of New Jersey. Ironically, though the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, the city was rather passive in the face of invasion, in keeping with its “get along” ethos.

Tidewater provided the military and political leadership of the revolt, but the Deep South didn’t get in on the action until phase three, when it was invaded and its caste system undermined (here, the narrative of The 1619 Project might hold more water, though it’s still tendentious). Its war became a savage, multi-sided conflict, with slaves executed out of fear of revolt, First Nation villagers massacred in the backcountry, Appalachian white trash ambushing Deep Southern oligarchs, and the Redcoats in the middle punching left and right.

Once Yankeedom, Greater Appalachia, and Tidewater achieved final victory—thanks to the vengeful assistance of France—the fleeing Brits evacuated tens of thousands of emancipated slaves, Midlanders, and New Netherlanders (the Loyalists) to Canada. There, the Crown exercised the orderly rule it had intended for all the colonies. The reason Canada today is animated by good, moderate, wise government is because of the preponderance of Midlanders who settled there post-1783—their communitarian ethos allows it to hold together its diverse nations in a balanced brew.

III. American Unions (1783-1815)

Such civility would not be found further south. As Woodard puts it, the history of the United States after 1783 boils down to a death match between its two dominant ethno-nations: Yankeedom and the Deep South. These regions are polar opposites, the first being essentially a democratic socialist nation, the latter amounting to a proto-fascist regime based on punitive authoritarian rule. Both are inherently expansionist, their worldviews fundamentally incompatible. Both try dominate the national government and impose their vision of the good society onto the entire federation.

Over the centuries, the smaller nations have joined one or the other of these Big Two in shifting Blue and Red coalitions. Today, the Blue coalition consists of Yankeedom, New Netherland, Tidewater, and the Left Coast (along with Greater Africa/Greater Polynesia/and the remnants of First Nation). The Red coalition consists of the Deep South, Greater Appalachia, and the Far West (with the remnant of New France thrown in). The Midlands, along with latecomer El Norte, serves as the swing region and kingmaker.

The first government of the newly-independent states, the Articles of Confederation, continued the war’s loose alliance of separate nations for the purposes of defense and trade (basically, today’s European Union). The adoption of the Constitution of 1787 turned the confederation into a full-blown federal state. In this new arrangement, the separate nations ceded sovereignty to an enhanced national government but retained significant autonomy (just how much has been a source of conflict to this day). The question is why? Why would these sovereign nations ever give up power?

There are several reasons. First, the government under the Articles was just too weak—everyone could see that. It had no power to tax or create monetary policy. It couldn’t regulate commerce nor control intellectual property. Moreover, the states (being independent) frequently nullified national laws and passed their own legislation—they worked at cross-purposes with each other.

Most troubling to the elites of Tidewater and New Netherland, the democratic ethos of the Revolution had (in their minds) run wild. State legislatures passed populist measure like canceling debts and introducing paper currency. Such laws were good for everyday people, but not for creditors. And creditors held the strings. When an rebellion by debt-ridden farmers broke out in Massachusetts—using the same tactics as they did against the Brits—the elites panicked.

Michael Klarman thus characterizes the convention as a conservative counter-revolution that suppressed democracy. The delegates achieved reforms that many people thought necessary—for example, federal power to tax and regulate trade. But it went farther than most wanted. It built in a bevy of oligarchic devices to insulate the government from the popular will, including a bicameral legislature with tiny numbers of representatives who served long terms of office (in the case of the Supreme Court, life). Senators were chosen by state legislatures and the President (who retained vestiges of monarchy like the pardon power) by an aristocratic Electoral College. It was a bloodless coup by fifty-five elites, the Thermidor of America’s Revolution.

The Constitution enumerated certain powers of the federal government. The rest they delegated to the states. Just how much is a conflict that’s plagued the federation to this day. The restive nations, uneasy with surrendering sovereignty, have insisted on governing their regions according to their unique cultural values. This has thrown them into conflict with federal authority—and each other—from the outset.

While fighting those battles, the nations also embarked on a various settler-colonial projects west, spreading an “Empire of Liberty,” as Jefferson put it. First Nation fought for every inch of its homeland—even building a vibrant new capital in Georgia, New Echota—and wielded substantial power throughout this period. The Indigenous nations frustrated many colonial projects and won major victories on the battlefield. But they were drowned out by the overwhelming tide of invaders.

The Yankees swarmed into the Northwest Territories around the Great Lakes. The Midlanders carved a strip across Ohio and Illinois into Iowa. Greater Appalachia poured down the Ohio River into Kentucky, Tennessee, and, eventually, the Hill Country of Texas. And Deep South spread its slave empire through the Gulf. Tidewater, ironically, got trapped on its Chesapeake beachhead. But it exercised outsize political influence in the new federation—its conservative brand of liberalism dominated the Convention of 1787, and it produced four of the first five Presidents.

New Netherland, meanwhile, exploded in population and exported its financial capitalism throughout the federation thanks to the efforts of its adopted son, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton served as Treasury Secretary under Washington (really more like his Prime Minister), and his plans—from the creation of a National Bank to the development of his “American School”—ensured that New Netherland would be the economic capital of the empire. After a final throw-down with the Brits during the War of 1812, the (kind of) United States cemented its territorial claims all the way to the Mississippi.

Far from a united endeavor, these colonial schemes continued to perpetuate what Alan Taylor has labeled separate American Republics. But the Spanish Empire still held sway in Florida and El Norte, the British in Canada, and the Russians in the Pacific Northwest. Even the French might return: Napoleon could, they feared, invade New Orleans and Louisiana the way he did tried with Haiti. In a world of powerful empires, the fate of the fledgling American Nations was far from certain. Especially when one considered their comically absurd diversity. As I said earlier, Canada’s federation consists of four like-minded nations: Yankeedom, First Nation, Left Coast, and New France. The Midlands, its dominant nation, is communitarian and moderate. The populist Far West represents its only right-leaning region, and even it can swing in a progressive direction. First Nation—with its communal living—and bohemian New France pull Canada Left.

The U.S. has the opposite phenomenon. The fascist Deep South and right-libertarian Greater Appalachia swap out First Nation and New France and yank the federation Right. The Founders of the Constitution feared that these nations—especially the expansionist Deep South and Yankeedom—were so opposed in worldview that they’d descend into another civil war. Hence their exhaustive labor to celebrate the new Constitution and promote the “Spirit of 1776.” The mystical nationalism that grew around the Union in the early 1800s (promoted by figures such as Yankee Daniel Webster and Tidewater Henry Clay) intended, like Moses and the Israelites, to bind the American tribes together around a new set of values. That’s why, as Woodard points out, it's so important for the U.S. to abide by its constitutional system. Without those shared rules of governance, there's little else tying the nations together. So, when the electoral system breaks down and different nations stop abiding by its results (as we're seeing now) violence follows. Such a crisis exploded in the middle of the 19th century—the subject of my next post.