[This post is Part III of a series. Here are links for Part I; II; IV; V; VI; VII; and the Epilogue.]

America, like the Bible, is the story of a people caught between slavery and freedom. And just as Exodus provides the interpretive key to the scriptures, so too does the Civil War make for the paradigmatic event of the United States. In ways we now appreciate anew, that war never really ended. Its fundamental choice of whether to emancipate the human spirit or crush it beneath the yoke of bondage endures. Every generation must take up this battle between equality, democracy, and liberty on the one hand, or hierarchy, despotism, and chains on the other. Mostly, the American nations fight it out at the ballot box, through the press, and in the courts. But from 1861-1877, they slaughtered each other through fields, on rivers, in the streets.

I. The Third American Civil War

Every one of the American nations introduced enslaved Africans to its territory during the colonial period. And as David Hackett Fischer illustrates in African Founders, slavery was everywhere awful. It broke bodies, minds, and souls. It proclaimed social death for its victims, exclusion from the body politic and even the human family. The physical damage from overwork endures on the skeletal remains of bonded people. In no place was slavery benign, paternalistic, or civilizing. In no place were the enslaved people happy, loyal, or content. On the contrary, all resisted captivity in ways great and small.

At the same time, slavery was a protean institution. It wasn’t the same in Yankeedom as in the Midlands. And none was a brutal as the Deep South. The northern nations were societies with slaves; the southern were slave societies. In New Netherland, Yankeedom, even early Tidewater, substantial numbers of enslaved people rose out of their station and obtained property, wealth, and a modicum of freedom. Such tales of upward mobility, though, never happened down south. In the Carolinas and Georgia, slavery was a totalitarian system from which few Africans escaped.

The planter class made the institution constitutive of their identity and way of life. This differed from the Yankees and Midlanders—even from folks in Greater Appalachia. We see this in the fact that shortly after the War of Independence, the northern nations began to abolish the institution, beginning with Yankeedom in the 1770s and ‘80s. The war galvanized the abolitionist movement, led especially by Quakers of the Midlands—Pennsylvania introduced a gradual abolition law in 1780.

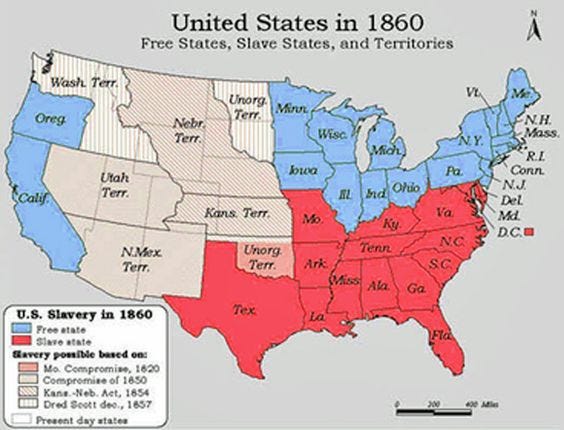

But only in the north. In the southern nations—Tidewater, the Deep South—slavery became stronger after the revolution, not weaker. And with the invention of the cotton gin, gang labor agriculture became more lucrative than ever. The population of the enslaved burst to almost 4 million by 1860, the planter class the richest, most powerful men in the country. As abolition stalled at the Mason-Dixon Line by 1815, two blocs emerged within the federation, one slave, one free. Far more than an abstract discussion, the conflict over slavery that played out over the next sixty years was an existential struggle between two diametrically opposed worldviews: that of Yankeedom and Deep South.

By 1846, after the United States conquered El Norte in an imperial war of colonial aggrandizement, the conflict came to a head. Would these new territories, seized by force, be slave or free? I’ve posted several detailed explanations of the antislavery platform of Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party in the 1850s, so I won’t rehash their ideology. Just remember that, contrary to The 1619 Project, it was their express plan to put slavery on the road to ultimate extinction. They meant to do so through a series of peaceful policies and, if war broke out, military emancipation.

With Colin Woodard’s thesis in mind, we can now see the Civil War and Reconstruction as, essentially, an attempt by Yankeedom to invade, occupy, and reconstitute the Deep South—to nation build within the federation. In its initial effort to destroy slavery, bring down the planter class, and suppress treason, the Yankees found allies among the Midlands and Greater Appalachia. Together, this coalition won the first phase of the conflict. Then Yankeedom decided to go farther: to remake the Deep South in its own image, based on free labor, civil rights, and biracial democracy. At this point, Appalachia (always hostile to big government) fled the coalition and sided with the Deep South.

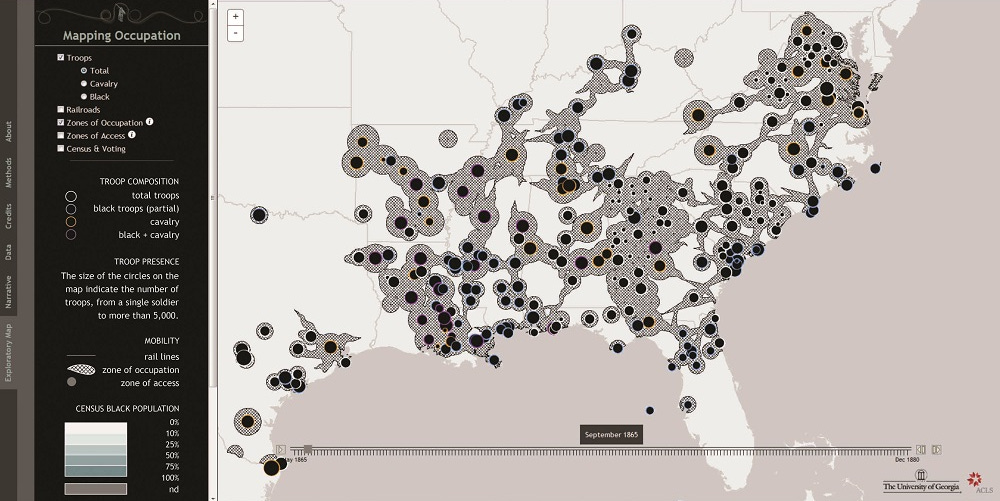

The Yankees and Midlanders sent scores of soldiers, teachers, businessmen to the region to change its culture. They worked with emancipated and free Blacks to build a political coalition based on equality. They even rewrote the Constitution to enshrine these higher values. Initially, they met with success. But they failed to provide enough security or sustain the occupation, and the ex-Confederates mounted a counter-attack of domestic terror unparalleled in Western history.

As the Yankee public grew weary with the white supremacist backlash—and more interested in colonizing the Far West—they took their foot off the gas and pulled out, leaving Black folks to the tender mercies of their former tyrants. Ulysses Grant bitterly remarked after his presidency that Yankeedom should have occupied the Deep South for fifty years. But there wasn’t the will.

II. The Triumph of Yankeedom

From the fall of Reconstruction until 1932, the story of the American nations took a paradoxical turn. On the surface, the conflict between the giant blocs cooled down. The Far West was brought into the fold, and the Left Coast became more and more a free-wheeling paradise. The Deep South reimposed its caste system on the region, while progressive reformers in Yankeedom, the Midlands, and the Far West repackaged the slavery-freedom fight into new terms: labor v. capital.

Boosted by the engine of war, the industrial revolution entered its monopolistic stage in the 1870s. Oligarchs like Andrew Carnegie and J.P. Morgan exercised dangerous new powers. Inequality exploded to untold levels, with most of the wealth placed in the pockets of a few. Opposed to these robber barons was a rising tide of socialists, populists, and religious reformers led by dynamic figures like Eugene Debs and William Jennings Bryan. They hailed from Yankee cities, the Midlands, and the Far West, and achieved victories large and small.

Shadowing their comrades in Europe, the Socialist Party in America grew into a powerful mass movement. Debs tallied nearly a million votes in the presidential election of 1912, six percent of the total. By 1913, it seemed like socialism might actually lead the world to a post-capitalist future. Then, disaster. The Great War shattered the solidarity of the world’s working classes. Four years of total combat destroyed a generation and destabilized the liberal republics of the West. On the surface, laissez-faire capitalism kept the party going during the Jazz Age. But in October 1929, the lights finally went out.

With the Wall Street crash, the American nations entered their darkest period since 1865. Millions were thrown out of work, demobilized war veterans adrift across the landscape. The feckless response of conservatives like President Herbert Hoover prompted many citizens in Europe and the U.S. to turn against self-government. On the Left, inspired by the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, radicals embraced communism. On the Right, the masses looked to the fascist alternative pioneered by the Deep South. Though most successful in Italy and Germany (where the Nazis copied the race laws of Jim Crow), the national socialist movement gained shocking power at home. The American nations faced the same cross-roads: barbarism or socialism, enslavement or freedom.

Here, luck saved the federation. The Depression was so catastrophic that it utterly discredited both the unregulated capitalism of New Netherland and the cultural conservatism of Tidewater. Meanwhile, folks in the Far West had cried out for government help against heavy industry since the 1870s—the most powerful unions were established in there. In the election of 1932, as Germany went to the Nazis, the federation took a chance on the social democratic agenda of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt, a New Netherlander who betrayed his class, had become the champion of Yankeedom’s central planning. Over the next twelve years, he proved its ideology successful.

The New Deal was a unique event in the history of the American nations. For once, Yankeedom and the utopian dreamers of the Left Coast had a popular mandate to establish social democracy. Their success was incredible. Over eight years, New Deal programs created more than 20 million jobs. These workers built 39,000 schools, 2,500 hospitals, 325 airports, and tens of thousands of smaller projects. The Civilian Conservation Corps put 275,000 young men to work in its first summer clearing trails, building parks, and restoring the soil. “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” went on to employ close to three million workers and plant over three billion trees.

The New Deal never implemented full-blown socialism. But it came as close as the U.S. ever has—what some have called “moral capitalism.” It established Social Security, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Its Works Progress Administration built hundreds of public works to expand the physical commons. Its Federal Theatre Project was the centerpiece of the most robust public arts program in the nation’s history. The purpose of these initiatives was not just economic relief. It was to cultivate a democratic culture—new values of community and public goods that were the hallmarks of citizenship. It was a campaign for hearts and minds.

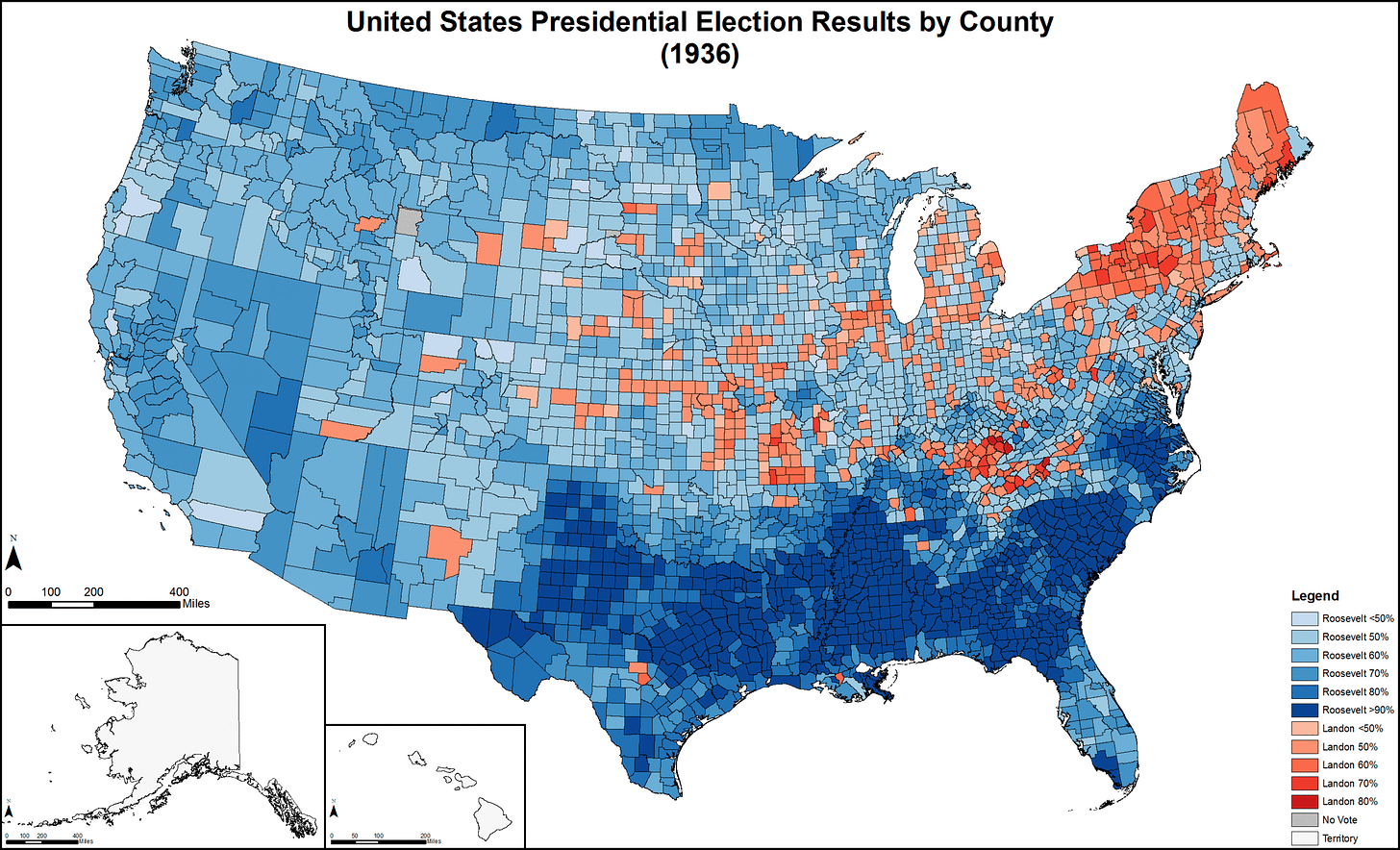

But what of Deep South and Appalachia? How did cultural fascists and right libertarians—opposed to large government and labor regulations—embrace the Yankee coalition? Here, a fateful bargain was struck—the New Deal would not touch the racial regime of the old Confederacy. African Americans benefitted from many of the labor and social programs of the Roosevelt Administration, which won swung their electoral allegiance from the Republican Party to the Democrats. But their civil rights went unprotected, and the Deep South consistently forced Roosevelt to take half a loaf on many programs.

As for Appalachia, the New Deal directed some of its most successful initiatives—like the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Rural Electrification project—to that very libertarian region. Finally, the Scots-Irish of the region got a glimpse of how government—when under popular control—could improve their communities. The New Deal was, among other things, a process of nation-building that expanded on the initial efforts of Yankeedom during Lincoln’s administration.

It worked. Roosevelt’s administration staunched the bleeding, put down a safety net, and blunted the rise of domestic fascists. FDR won three more terms in successive landslides. When their European cousins launched a new global conflict, FDR rallied the federation to fight fascism abroad. The Second World War continued to unify and democratize the American nations. After all, nothing binds squabbling tribes together like a common foe. It proved the greatest example of how a democratic government can plan an economy and remain an open society.

In the decades after victory, Roosevelt’s successors continued his egalitarian agenda. Inequality and poverty were slashed as the government taxed the wealthy to redistribute resources for all sorts of programs. Unions grew strong. Standards of living increased. For thirty years, the American nations learned the lessons of the inter-war period: an activist government that creates greater equality, democracy, and solidarity reaps peace and prosperity.

III. Rise & Fall of the Second Reconstruction

But people forget. By the early ‘50s, the old fissures between the Blue and Red blocs started to awaken. WWII, like the civil wars of 1776 and 1861, unleashed revolutionary impulses. After they tasted liberation during the war, women and African Americans began to demand their full participation as equal citizens. The Civil Rights, feminist, and gay movements got underfoot in the 1950s and ‘60s, the logical extension of the New Deal’s expanded social contract. But with this cultural shift, the fragile peace between Yankeedom and the Deep South came undone.

Unlike Roosevelt, Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy could not stand by as southern states used brutal tactics to re-impose apartheid. Appealing to the precedent of Ulysses Grant, they sent in federal forces—even the Army—to desegregate the region. The Second Reconstruction was thus a new attempt by Yankeedom to enforce racial equality and democracy in the Deep South and also reckon with its own structural racism.

Once again, it made tentative gains. The high tide came when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act in the mid ‘60s. Johnson was an Appalachian native who converted to the Yankee ideology when he witnessed how the New Deal rescued his region from poverty. When he assumed the presidency in 1963, he vowed to continue the legacy of FDR and launch the next phase of the utopian project: the Great Society. It was a noble, flawed endeavor. But once he betrayed the Deep South by backing civil rights, he plunged the American nations into a cold war.

Over the next fifty years, the Red bloc of Appalachia and the Deep South launched a full-scale counter-revolution—just as they’d done in the 1870s. It was touch-and-go at first. Barry Goldwater, inspired by Herbert Hoover no less, was crushed by LBJ in 1964. But Vietnam broke the Left, and the Red coalition took the presidency with Nixon’s “Southern strategy.” Tricky Dick kept the New Deal consensus in place—he even tried to pass a Universal Basic Income. But the “law and order” mentality of the Deep South had won back the national narrative. Jimmy Carter, a son of Georgia, regained the White House for the Blue bloc, only to acquiesce to the cultural revanchism of his home nation.

Then, the economy handed the Red bloc a golden opportunity. By the late ‘70s, the post-war catch-up boom had run its course. Growth rates returned to normal levels. Combined with a manufactured oil crisis, this led to the infamous period of stagflation. The Tidewater conservatives and the bankers of New Netherland saw an opening to regain the wealth they’d lost. Using a Left Coast traitor—B-movie actor Ronald Regan—as their salesmen, they convinced the federation that the regulatory policies of Yankeedom were stifling GDP. The children of FDR’s generation discarded the lessons of their parents, and gave the keys to the kingdom back to free-market capitalists.

With the accession of Reagan, the Red bloc—combined with Tidewater and New Netherland elites—took an axe to the New Deal. They broke unions, slashed regulations, and cut taxes on oligarchs. Workers were decimated, and over the next forty years, inequality surpassed even the levels of the Gilded Age. For its part, the Blue coalition abandoned its old values and bought into the restored neoliberal order. Bill Clinton took back the White House for the Yankee alliance, but ceded the argument to the Red one. He cut welfare benefits, promoted education as the sole path to opportunity (as opposed to social democracy), and aimed for balanced budgets. The era of Big Government, he announced, was over.

Just as in the 1920s, the regnant neoliberal order juiced the economy for the upper classes and deluded the masses with a message that greed, selfishness, and individualism are good. Turbocharged by the Dot-Com bubble, the ‘90s was a party for the rich. Meanwhile, wages collapsed for the vast majority. And just as in the ‘20s, it led to catastrophe. By 2000, the Red and Blue blocs had swapped parties and sorted themselves into pure partisan alignment—almost a mirror image of the old slave state/free state divide.

In fact, they were so evenly divided that it took a ruling by the Supreme Court to determine the winner of the presidential election. In an echo of the Great War, the Tidewater neocons of George W. Bush threw the federation into military debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan that created a new disaffected generation. Come 2008, it was deja vu all over again: the bankers of New Netherland once more took the global economy off the fiscal cliff. As the world order cracked up a second time, the American nations faced their old choice: slavery or freedom. Which road would they take now?