[This post is Part VI of a series. Here are links for Part I; II; III; IV; V; VII; and the Epilogue.]

I. Introduction

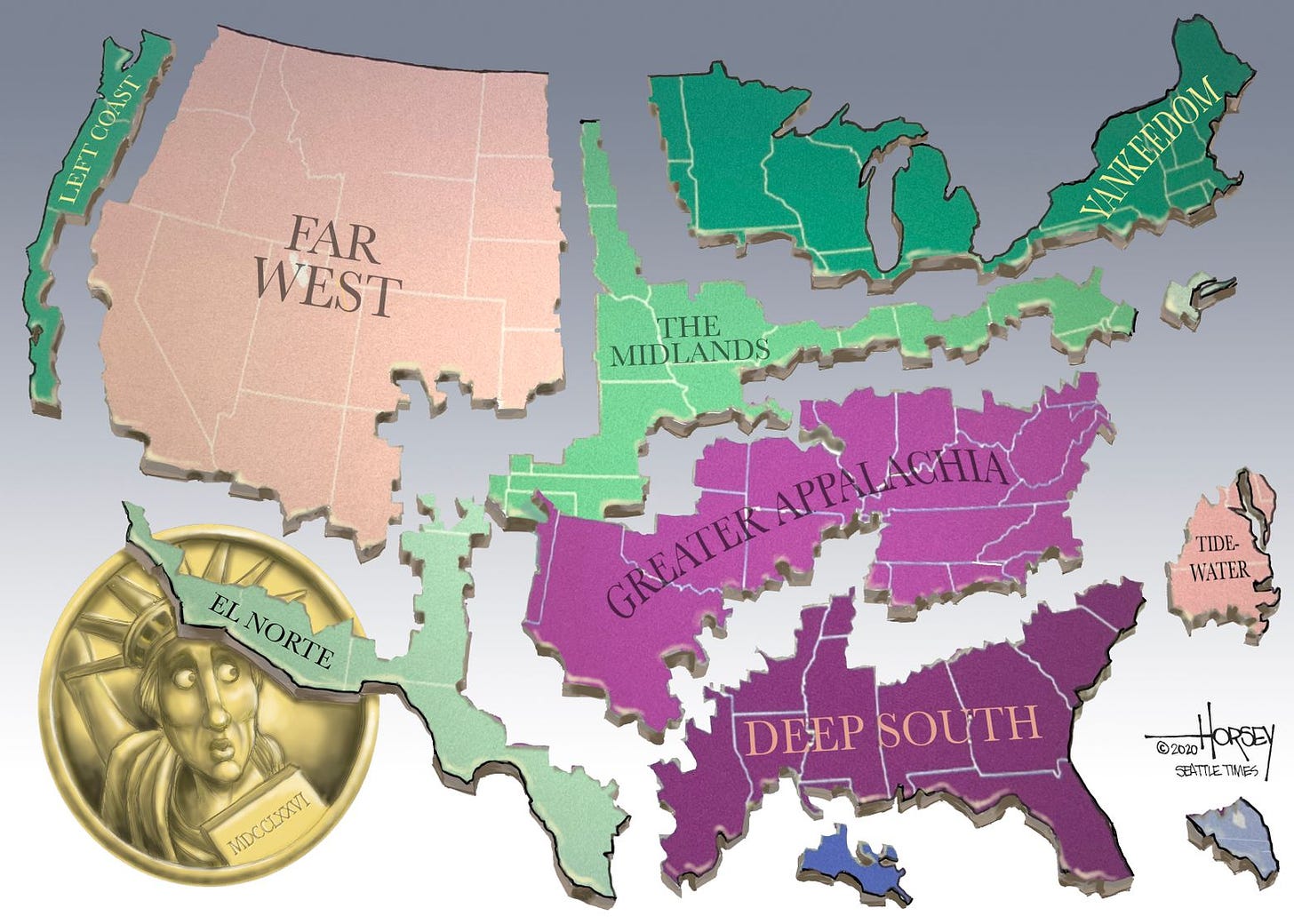

Let’s return to our American Nations series and continue to devise an electoral prescription for socialists. We’re almost to the end, I promise! Last time, I focused on just the first of a five-point plan—learn the cultural values of the Midlands, El Norte, and Yankeedom and connect them to leftist ideas. I want to cover the second two points today:

Make residents in the rural counties of those regions feel heard and respected.

Deliver a Sanders-style message of cultural moderation and economic populism through stories that will resonate emotionally.

The entire thesis of Colin Woodard’s book is that the most salient divide in the United States is between the dozen or so ethno-nations within the federation—not the rural/urban one. Yet it’s an empirical fact that within the various nations—especially the crucial ones of the Midlands, El Norte, and Yankeedom—the rural/urban split has become the deciding factor. The defection of backcountry Yankees to the Dixie bloc explains Trump’s 2016 win and Biden’s squeaker of a victory in 2020. The same dynamic’s at play in the Midlands and El Norte. In my last post, I touched on how to win back these voters, drawing from Chloe Maxmin’s new book, Dirt Road Revival. Let’s unpack her argument more and home in on rural America.

II. Listening to Rural America

To begin with, why talk about the hinterlands at all? Don’t more people live in cities and metro areas? Yes. But as Maxmin illustrates, rural voters exercise disproportionate influence on elections. As the United States urbanized, our political system failed to adjust and reflect this demographic shift. The result is that the vote of a rural person has—by orders of magnitude—greater weight than that of city dwellers. The U.S. Senate, for example, is absurdly skewed in favor of the former, who get four times as many senators per person as urban residents. Gerrymandering has compounded this phenomenon, giving Republicans almost 40 House seats between 2012 and 2016 they would not otherwise have secured. In 2016, Trump claimed two-thirds of rural voters and won the Electoral College. In short, the Left has to attend to these voters to have a prayer of winning.1

Believe it or not, rural voters were about equally divided in their partisan leanings from 1999 to 2009, according to the Pew Research Center. And while losing the rural vote in 2008, Barack Obama improved on the performance of his predecessors, John Kerry and Al Gore. But over the course of his presidency, the Democrats began to hemorrhage support in these regions. Republicans flipped 965 state legislative seats during his tenure, with the Democrats flipping only 5. Hillary Clinton’s share of the rural vote in 2016 was 50% less than Obama’s, as was Biden’s in 2020. Today, the GOP holds a 16-point advantage (54%-38%) among these voters.2

What happened? I noted Katherine Cramer’s reporting on Wisconsin last time, how she found a wellspring of resentment among rural residents. They expressed “a sense that decision makers routinely ignore rural places and fail to give rural communities their fair share of resources,” she says “as well as a sense that rural folks are fundamentally different from urbanites.” She’s quick to point out that this belief isn’t actually true—rural communities don’t, in fact, receive fewer government dollars per capita than urban ones. If anything, they receive more. But their grievance speaks to a larger perception:

There is a logic to it, in the sense that people see the poverty in their communities and they see the wealth in urban communities, and draw conclusions from that. It may not be true that the government spends more on the cities on a per capita basis, but everybody knows that if you want a high-paying job you’re going to have to move to a city.

We’re in the realm of feelings here, not reason. But rural communities really are suffering. Here’s an example: My parents retired to the Adirondacks in recent years, prompting me to make frequent visits to Hamilton County in New York’s North Country. The county is the third-largest in the state by square miles, as big as the entire state of Delaware. But it boasts a population of only 5,107—one of the tiniest in the state and the least-densely populated county east of the Mississippi. Dominated by wilderness, it has no hospital, no pharmacy, no nursing home, only one resident doctor, and few social supports. Domestic violence, substance abuse, and high unemployment in the winter all strain the few available services, which struggle to provide relief.

This profile fits a pattern. Across the United States, rural hospitals have been closing, leading to a 6% increase in mortality. Farms have gone the way of the dodo, dwindling from 7 million a century ago to 2 million today. In 2019, the projected farm income was in the bottom quartile of all of the years since 1929. Almost 60% of rural Americans name lack of broadband access as a problem in their community, along with cell coverage. Indeed, on my drives through Hamilton County, the cellular dead zone stretches for miles—in 2022.3

Meanwhile, deaths of despair plague the landscape, driven by loss of jobs, community, and hope. Middle-aged white voters without a college degree are dying of opioids, alcohol, and suicide at unprecedented rates. Population growth has fallen from 8% in the ‘90s to 3% today. These regions are aging rapidly, as youth flee to burgeoning cities that offer schools, careers, and vitality. Since the Great Recession, 72% of employment growth in the U.S. has occurred in urban areas. Rural unemployment levels have remained higher than they were before the crash. As Tara Westover says in her memoir, Educated (2018), “There are places in the United States where the recession never ended. For them, it has been 2009 for 10 years. That does something to people, psychologically.”4

In the midst of this struggle, rural folks believe they’ve been forgotten by Democrats. They feel ignored, taken for granted, looked down on. They perceive the Democratic Party (correctly) as controlled by established elites who cater to limousine liberals in urban playgrounds. Comments like Obama’s 2008 remark that country folk “cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them,” or Hillary’s 2016 description of Trump’s supporters as a “basket of deplorables” confirm the condescending tone rural voters imagine Democrats use in private.

On top of these gaffes, Democrats have all but given up on these communities. The Party has paid state campaigns scant attention for years, focusing instead on national elections. From 1978 to 2009, the Democrats controlled both chambers in about 30 state legislatures. That number dropped to 13 in 2017. It controlled at least one chamber in 60 legislatures as of 2010; six years later, just 30. Late in her 2016 presidential run, Clinton assigned a single solitary staff person to rural outreach. Tom Perez, the chair of the DNC, said outright in 2018 that “you can’t door-knock in rural America.” After the 2010 midterms, Nancy Pelosi scrapped the House Democratic Rural Working Group and Harry Reid liquidated its sister group in the Senate. And Obama, incredibly, demobilized his entire volunteer organization after 2008—"the widest, deepest, and most effective grassroots organization ever built to support a Democratic president," said organizer Marshall Ganz.5

When the Democrats do make a play for rural votes, they often botch the campaigns by bringing in expensive consultants from out of state who know nothing about the locals. These city slickers apply a one-size-fits-all approach and conduct polls instead of conversations. And rather than talk to rural voters on the basis of values, Democratic candidates speak the wonkish language of technocrats. They fail to brand and market their ideas in terms that everyday people get on a gut level. Trump labeled his 2017 subsidy for the rich “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” While deceitful, it’s a simple title that sounds good. Who could be against tax cuts and jobs? As James Carville said, Trump was always in sales. And “Build the Wall” sells better than “Build Back Better.”6

The result is that the GOP has a lock on places like Hamilton County, which is one of the most conservative in New York. But it doesn’t have to be so. Maxmin goes on to narrate the story of her successful Democratic campaigns in deep-red Maine. From these case studies, she offers lessons and strategic principles for the Left to win back dirt-road voters. While acknowledging that many Trump followers are beyond our reach, she insists there still exist enough persuadable people in these places to tip the scales into the Left’s direction. Here are her recommendations:

Commit

Be Authentic

Be Creative

Be Resourceful

Not Me, Us!

Youth Lead

Respect Wisdom

Always Be Learning

Stay Connected to the Party, Not Big Donors or Party Elites

Respect Everyone

Listen

Translate to Rural America

Values, Not Party

100% Postive Campaign

Build Community

Take Care of Yourself and Others

Pass It On

It’s All a Social Movement

I touched on the importance of translating to rural America and preaching values, not party last time. Let’s expand on three more, in Maxmin’s words:

Be Authentic:

Rural voters seek candidates who say what they believe, with conviction and emotion, even when they know the listener won’t agree. In the case of Chloe and Sanders, this authenticity is further backed by ironclad integrity that leaves little doubt that they will walk their talk...Over and over again, we heard voters express a desire for candidates who are not cut from the same cloth and don’t represent politics as usual…When you show up as your authentic self and your actions line up with your words, voters begin to trust you. People are much more inclined to vote for someone thy trust, even if they don’t agree with their entire platform.7

Stay Connected to the People, Not Big Donors or Party Elites:

No matter what your fundraising approach is, remember that the most important people to talk with are the folks on the ground. When we talk with voters, we don’t show up and simply preach our gospel. We listen to people to learn where they are, and we make sure that our campaign is reflecting that reality. An unwavering commitment to stay connected to the working class and rural people is a must in order to achieve long-term success.8

Listen:

People always ask us how we won. Our biggest answer is listening. We cannot emphasize this enough…We live in a democracy that is woefully disconnected from and unrepresentative of the people it is supposed to serve….In this oligarchical society, and in this digital century, it is a radical act simply to who up, meet a person face-to-face, look them in the eye, and listen. As it turns out, people have a lot to say…When you’re campaigning, see people as humans, and focus on areas of agreement. What are our common hopes, dreams, fears and frustrations? When we listen, the tendrils of trust begin to sprout out of fallow ground. The possibility of a relationship grows. Even if we don’t convince the other person, we become a little bit more open to each other’s ideas, interested in each other’s experiences.9

None of this guarantees success, but failing to try promises defeat.

III. Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins

Point three: Deliver a Sanders-style message of cultural moderation and economic populism through stories that will resonate emotionally. As you can see, this is really two ideas in one. The first half refers to the content of the Left’s platform. The second indicates the way to deliver that content. I’ll take them in reverse order.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt sums up human nature in a pithy phrase: The mind doesn’t live in a rational world driven by facts. It lives in an emotional world driven by story. He likens our rational mind to a tiny rider sitting atop a huge emotional elephant. In her study of rural Louisiana, Strangers In Their Own Land (2017), Ari Hochschild reveals how Americans in these regions tell themselves a “deep story” that gives them an identity and pushes their politics to the right. This is a gloss on Woodard’s thesis, really—that each ethno-nation in the American federation has a unique history that constitutes its identity. Because of the narrative structure of our minds and our regions, political persuasion takes place on the level of story. When it comes to campaigns, then, the Left—after listening to rural America—also must weave the most compelling, dynamic, resonant stories possible.

Fortunately, we don’t have to fly blind. Consultant Annette Simmons has penned the Bible on story in two volumes: The Story Factor (2000, rev. 2019) and Whoever Tells the Best Story Wins (2015). She offers the following definition of story:

I define story as a reimagined experience narrated with enough detail and feeling to cause your listeners' imagination to experience it as real.10 A story is a narrative account of a significant emotional event or events that demonstrate relational truths. The difference between giving an example and telling a story is that story constructs an imagined scenario that portrays the consequences and opportunities of human choices over time...Stories are "more true" than facts because stories are multi-dimensional. Truth with a capital "T" has many layers.11

Bismarck called politics the “art of the possible.” But just what is possible depends on our ability to persuade others. When we try to persuade people, we seek to influence them. Simmons notes that “the concept of self-interest lies at the core of any psychological model for influencing others…The self seeks to achieve what it wants—whether it is profit, destruction, justice, or martyrdom. The psychological goal of influence is to connect your goals to your listeners’ self-interest in some manner.” Too often, influence—especially in politics—is sought through force: we try to coerce or compel someone do what we want. This is a “push” strategy, a power struggle in which one party wins, the other loses. Story, on the other hand, is a “pull” strategy. It has a “quality of graciousness that bypasses power struggles,” she says:

A push creates another push back. When using story, it is possible to invoke a new dynamic where pull attracts pull. It is more stable to find stories that pull (pool) interests together rather than perpetuate an unsteady competition between self-interests.12

Stories are like software you insert into people’s minds that generates new perceptions from within. The seeds of story germinate into flowers that pull people into your worldview and attract them to your cause. Stories work on people’s unconscious mind, hitting them in a less analytical way than facts and hypnotizing them into a receptive state of awareness akin to a child’s. “Repeating a story over and over or telling a powerful story that people remember over and over etches detail into the brain that the emotional mind cannot distinguish from real events,” she explains. “Once ‘installed,’ emotional triggers from story memories work behind the scenes to influence perception as effectively as ‘real’ memories.”

Stories connect with our common humanity; they unearth the fundamental condition we all share, which supersedes the cramped ideologies that divide us. Indeed, ideologies themselves are stories—they’re mental maps that organize our chaotic reality and its deluge of information into coherent, meaningful narratives. That’s why facts—disconnected from a new story—fail to change our minds. We simply take what’s presented to us and slot it into our default narrative in a way that reaffirms our bias. The capacity to rationalize our worldview and ignore, minimize, or explain away inconvenient truths is bottomless. “People need story to organize their thoughts,” Simmons continues:

In fact, anyone you attempt to influence already has a story. They may not be aware of the stories they are telling themselves, but they exist. Some people have stories that make them feel powerful. Others have a victim story, a story that proves your issue is not their problem, or a story that justifies their anger, frustration, anxiety, or depression. If you tell them a story that feels more meaningful, you can reframe the way they make sense, organize their thoughts, the meanings they draw, and thus the actions they take. If you can help people see themselves as part of something bigger than themselves, they may begin to see obstacles as challenges, and choose behaviors that sustain society as well as personal wins. Change their story and you change their behavior.

Look around at our political circus, and you’ll see a bunch of overgrown adolescents slinging mud. What passes for debate amounts to yelling loudly that the other side is wrong, our’s right. Glance at cable TV or Twitter for ten minutes and you see what I mean. I’m guilty of it myself. I’m utterly convinced that if I can just mansplain all my knowledge to political opponents, they’ll see its brilliance and bow down in humility before the All-Wise Coccoma. But contrary to conventional wisdom (and my know-it-all instincts), “you don’t have to convince people they are wrong to influence them,” Simmons says:

In fact, getting someone to admit he or she is wrong is a losing battle because it invites the ego to war. Egos fight blindly and viciously to be right because being wrong feels unsafe. Let your listener’s ego sleep. Concentrate instead on providing a visceral experience of a new point of view of their story so new choices make sense. Don’t back someone into a corner. Don’t preach down to them. Let them sit back and enjoy their familiar story from a novel point of view.13

How? “If you peel any human being’s ‘wish list’ back to its core,” Simmons explains, “they all look very much the same. The master storyteller knows this…If your story can tap into core human needs that we all share (belonging, safety, love), you’ve got yourself some pretty good bait.” She enumerates six basic kinds of stories that anyone seeking influence must master:

Who-I-Am Stories

What qualities earn you the right to influence a particular person? Tell of a time, place, or event that provides evidence that you have these qualities. Reveal who you are as a person. Do you have kids? What were you like as a kid? What did your parents teach you? What did you learn in your first job? Get personal. People need to know who you are before they can trust you.

Why-I-Am-Here Stories

When someone assumes you are there to sell an idea that will cost him or her money, time, or resources, it immediately discredits your “facts” as biased. However, you chose your job for reasons besides money. Tell this person what you get out of it besides money. Or if it is just about the money, own it.

Vision Stories

A worthy, exciting future story reframes present difficulties as “worth it.” Big projects and new challenges are difficult and frustrating for implementers who weren't in on the decision. Without a vision, these meaningless frustrations suck the life energy out of a group. With an engaging vision, however, huge obstacles shrink to small irritants on the path to a worthwhile goal. But be careful, because Vision stories that promise more than they deliver do more damage than good.

Value-in-Action Stories

Values are subjective. To one person, integrity means doing what his or her boss tells him or her to do. To another, integrity means saying “no” even if it costs his or her job. If you want to encourage or teach a value, you have to provide a “demonstration” by telling a story that illustrates in action what that values means, behaviorally. Hypothetical situations sound hypocritical and preachy. Be specific.

Teaching Stories

Certain lessons are best learned from experience, and some lessons are learned over and over again—patience, for instance. You can tell someone to be patient, but it’s rarely helpful. It is better to tell a story that creates a shared experience of patience along with the rewards of patience. A three-minute story about patience may be short and punchy, but it will change behavior much better than advice. It is as close to modeling patience as you can get in three minutes.

I-Know-What-You-Are-Thinking Stories

People like to stay safe. Many times they have already made up their minds with specific objections to the ideas you bring. They don’t come out and say, “I’ve already decided this is hogwash,” but they might be thinking it. It is a trust-building surprise for you to share their secret suspicions in a story that first validates and then dispels these objections without sounding defensive.14

For each of these categories, Simmons encourages us to come up with stories that fit into one of four sub-genres:

A story about a time we shined;

A story about a time we blew it;

A story about a mentor who taught us something;

A story from a movie, book, or current event.

The Left, then, must craft these kinds of stories to convey its values—especially when talking to rural voters. For, as the title of Simmons’s book says, whoever tells the best story wins. Not the most accurate. Not the most complex. The best. Haidt puts it well:

An effective political preacher offers a clear moral vision of America. That vision includes a historical narrative about where we went wrong, and then tells us how we can set things right. It also includes strong moral arguments that connect with and validate the moral judgments of voters.

In 2016, Donald Trump had a story. His tale of “American Carnage” was self-serving, destructive, and a lie. But it was a story—and a powerful one at that.15 Orwell chronicled the appeal of fascism in his day, in contrast to the hedonic promise of materialist liberalism:

Whereas Socialism, and even capitalism in a more grudging way, have said to people ‘I offer you a good time,’ Hitler has said to them ‘I offer you struggle, danger and death’, and as a result a whole nation flings itself at his feet. Perhaps later on they will get sick of it and change their minds, as at the end of the last war. After a few years of slaughter and starvation, ‘Greatest happiness of the greatest number’ is a good slogan, but at this moment ‘Better an end with horror than a horror without end’ is a winner.16

Hillary Clinton, in contrast, had no story. And in a contest between a bad story and no story, a bad story wins every time. To be fair, the Democrats crafted a highly emotional narrative at their convention that year. They leaned into a “Duty, Honor, Country” theme, and trotted out a parade of everyday folks who’d been victimized by Trump over the decades. This painted him as a freeloader and a cheat, a con artist who'd left a trail of bitter, resentful customers and partners in his wake. This narrative touched deep moral intuitions about fairness versus exploitation.

The climax came when the convention introduced Khizr and Ghazala Khan, the immigrant parents of Army Cpt. Humayan Khan, who was killed in Iraq in 2004. When the fallen soldier’s father brandished a copy of the Constitution and asked Trump if he’d ever read it, the image spoke right to the “elephants” of the American people. In Haidt’s typology, it touched on the moral foundations of loyalty, authority, and sanctity in one fell swoop. The Constitution—a foundational text in the American canon—was literally held up to venerate. Viewers were reminded that Trump was desecrating its norms by violating all standards of political decency—not to mention refusing to honor the outcome of the election if he lost. The ultimate devotion of their son to the flag contrasted with Trump’s flaming narcissism and traitorous associations with America’s enemies. And for all of his talk of law and order—“I alone can fix it”—the question underscored that the Manhattan mogul was a chaos candidate one step ahead of the law. Khan ended with a devastating declaration to Trump: “You have sacrificed nothing and no one.”

The dichotomy between the Democrats’ honoring these quiet patriots and the sycophantic worship of the MAGA leader the week before was stark and clarifying. For once, Trump’s attempts to counterpunch backfired, as his attacks on the couple made him look even worse. I remember wishing the election would happen right then—Clinton opened a significant lead based on the weight of this electrifying story. Alas, there were months left to the campaign. In that time, Trump dragged the Secretary back into the muck and confused the public like a diabolical carney huckster. He used the checkered history of the Clintons to make them look just as bad as he. “We're both awful sleaze bags who break the rules,” he essentially said. “I’m just honest about it!” Clinton, meanwhile, struggled with three key stories—Who I Am, Why I’m Here, and the Vision. And without a I-Know-What-You’re-Thinking tale, she couldn’t dispel the suspicion among many (including me) that she felt the presidency was something she was owed.

IV. The Socialist Story

I’ll save most of my ideas about the content of the Left’s message for the next installment. For now, I want to bring it back to Bernie Sanders. As I’ve mentioned throughout this series, Sanders struck a chord with the very voters the Left needs to win. He didn’t look or sound polished and poised, which they liked. He had an ornery temperament, a blunt oratorical style that resonated with them. He looked frumpy, which struck folks as real. His combativeness suggested he was a fighter for the little guy. No matter the venue or question, he brought everything back to a few core ideas.

Those ideas essentially communicated a platform of economic populism and cultural moderation. Sanders is something of a throwback. Though a product of the Sixties, his politics feel more like that of a socialist from the ‘30s. He prioritizes pocketbook issues over identity politics and the culture wars. He hardly talks about guns, for example, and when he has, he’s spoken empathically about gun owners and staked out a middle ground for much of his career (though he’s moved left under criticism). It helps to remember that his 2016 campaign was an outgrowth of the Occupy Wall Street movement. The message of that uprising, as Haidt summarizes, was clear and simple:

Rein in the influence of big business, which has cheated and manipulated its way to great wealth (in part by buying legislation) while leaving a trail of oppressed and impoverished victims in its wake.

Haidt even created an animated short to envision the socialist narrative:

In preaching this gospel, the Left elevates the moral foundation of fairness from its second-place position (behind care) to first. The problem, though, is that there are three other tastebuds with which people make moral judgments—the sanctity, authority, loyalty ones mentioned earlier. Haidt lays out his typology as follows:

Care/harm: We feel compassion for those who are vulnerable or suffering.

Fairness/cheating: We constantly monitor whether people are getting what they deserve, whether things are balanced. We shun or punish cheaters.

Liberty/oppression: We resent restrictions on our choices and actions; we band together to resist bullies.

Loyalty/betrayal: We keep track of who is “us” and who is not; we enjoy tribal rituals, and we hate traitors.

Authority/subversion: We value order and hierarchy; we dislike those who undermine legitimate authority and sow chaos.

Sanctity/degradation: We have a sense that some things are elevated and pure and must be kept protected from the degradation and profanity of everyday life. (This foundation is best seen among religious conservatives, but you can find it on the left as well, particularly on issues related to environmentalism.)

Too often, the Left fails to weave a narrative that links all these intuitions, especially the last three. That’s because loyalty, authority, and sanctity are often put to the service of nationalism, and socialists are uncomfortable with such a feeling. The narrative of the Left revolves around justice, particularly justice as care and liberation from oppression. George Packer even calls this perspective “Just America.” Conscious of the country’s many sins, crimes, and evils, its song is a litany of lament:

Just America has a dissonant sound, for in its narrative, justice and America never rhyme. A more accurate name would be Unjust America, in a spirit of attack rather than aspiration. For Just Americans, the country is less a project of self-government to be improved than a site of continuous wrong to be battled. In some versions of the narrative, the country has no positive value at all—it can never be made better.

In this version of the Left’s story, “sacred” documents like the Constitution are hopelessly tainted by their compromise with slavery, exclusion of women, and genocide against indigenous peoples. Loyalty to the country is suspected as a slippery slope to nationalism. And the very idea of authority must be questioned—laws oppress, cops kill, and the armed forces are gangsters for capitalism. Whether these claims are true on the merits is a separate matter. The point is that in terms of story, such themes are overwhelmingly negative, depressing, and grim. If those are the only emotions socialists generate, we’ll never—repeat, never—entice people to join us. What coach would ever tell her team at halftime that they suck and have no chance of winning?

The United States is a settler-colonial empire. That’s an empirical fact. But as Virginia Woolf writes, “Nothing is just one thing.” America is an epic made up of heroes and villains, astonishing triumphs and unspeakable horrors. Like every drama, it’s full of contradictions, ironies, and mad folly. Many people want to connect with that story and write its next chapter. They may agree with you that the country’s profoundly flawed, on the wrong track, and in desperate need of repair. But start telling them the whole thing’s a racket founded on wickedness, and they’ll feel personally attacked. Hell, I’m a socialist and even I get my back up when a foreigner criticizes the U.S. I’ll bash my country myself, thank you very much! “An intelligent Socialist movement will use people's patriotism,” Orwell says, “instead of merely insulting it, as hitherto.”17 He elaborates as follows:

Nationalism is not to be confused with patriotism…By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes the best in the world but has no wish to force upon other people…Nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power. The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and more prestige, not for himself but for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his own individuality.18

You catch more flies with honey than with vinegar. If you want to motivate your listeners, you must give them a story of hope. You have to believe—truly believe—that as bad as things are, as many challenges as we have, we can overcome them if we come together and give our all. If you don’t, listeners will sense the resignation and your words will fall on deaf ears. People want to feel like they have agency to make their lives and their country better—that they’re the protagonists in their own adventure. An unrelenting message of injustice—uncoupled from a vision of how to rectify it—leaves them deflated and discouraged. Simmons says that all stories should be about three-fourths positive and just one-fourth negative. If it wants to influence the public, then, the Left needs to craft a narrative of American redemption—a tale that resonates with all five moral tastebuds. Fortunately, that rhetorical key lies latent in all of us. It’s America’s civil religion, and it’s to that crucial tradition that we’ll turn next time.

Chloe Maxmin, Dirt Road Revival (2022), 3-5; 23.

Maxmin, 7-8.

Maxmin, 10.

Maxmin, 10-12.

Maxmin, 28-30.

This is a truth that DNC bigwigs have to beat into their thick skulls. Many elites were enamored of Elizabeth Warren in 2020, with her catchphrase “I’ve got a plan for that.” This policy shop talk strokes the erogenous zones of educated liberals, trapped in their urban echo chamber. But can you think of anything worse to say to a rural voter? These people decide their support on whether someone looks, sounds, and acts like them—not their policy papers. Among these voters, Warren actually struggled more than Clinton, as The New York Times (which endorsed her) admitted. In fact, she’s performed poorly even among rural Massachusetts residents, which both Jacobin and Vox have detailed.

By contrast, Bernie Sanders has over-performed among rural voters throughout his career. Of the 61 Vermont towns that voted for Trump in 2016, Sanders won 47 in his 2018 Senate race. (By comparison, of 91 Trump towns in Massachusetts, Warren won only four. Among the state’s fifty largest towns that voted for Trump, she lost all fifty of them.) Taking these towns collectively, Clinton lost to Trump in 2016 by 8 percent; Bernie won them back two years later by more than 10 percent—a dramatic 18-point shift from Trump to Sanders. We can see the contrast most starkly at the town level. Take rural Barre in central Massachusetts. In the 2016 Democratic Primary, Bernie crushed Clinton, taking 68% to her 31%. Two years later, Warren lost it to her far-right challenger, Geoff Diehl, 51% to 44%. In 2020, Sanders won it again with 38% to Biden’s 30%. Warren, at just 15%, finished a distant third—in her own state.

Given that Bernie’s policies are even more to the left than Warren’s, to what do we ascribe the preference of rural conservative communities to Sanders over Warren? With Maxmin in mind, I’d offer that the direct, values-based style of Sanders connects more readily in the backcountry than the highfalutin discourse of a Harvard Law professor. Indeed, he raised more money than any Democratic primary contender in 2020 among Obama-Trump swing counties. (And his policies, for that matter, were actually more substantive, transformational, and fit for the country’s needs than Warren’s.) Like it or not, elections are popularity contests. Sanders is the most popular politician in America. Warren? One of the most unpopular. It’s not rocket science.

Maxmin, 83-84.

Maxmin, 92-93.

Maxmin, 94-96.

Annette Simmons, Whoever Tells The Best Story Wins (New York: Amacom, 2015), 22.

Annette Simmons, The Story Factor (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 36-38.

The Story Factor, 118-121.

The Story Factor, 168-169.

Whoever Tells The Best Story Wins, 24-26.

That’s because, despite the deniers, Trump is a fascist. And fascism—at its core—is a mental narrative. In Anatomy of Fascism (New York: Random House, 2004), Robert O. Paxton defines the ideology as “a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.” Fascism arises from a set of “mobilizing passions” rooted in a story:

A sense of overwhelming crisis beyond the reach of any traditional solutions;

The primacy of the group, toward which one has duties superior to every right, whether individual or universal, and the subordination of the individual to it;

The belief that one’s group is a victim, a sentiment that justifies any action, without legal or moral limits, against its enemies, both internal and external;

Dread of the group’s decline under the corrosive effects of individualistic liberalism, class conflict, and alien influences;

The need for closer integration of a purer community, by consent if possible, or by exclusionary violence if necessary;

The need for authority by natural chiefs (always male), culminating in a national chieftain who alone is capable of incarnating the group’s historical destiny;

The superiority of the leader’s instincts over abstract and universal reason;

The beauty of violence and the efficacy of will, when they are devoted to the group’s success;

The right of the chosen group to dominate others without restraint from any kind of human or divine law, right being decided by the sole criterion of the group’s prowess within a Darwinian struggle.

George Orwell, Orwell and Politics (UK: Penguin, 2021), 85.

Orwell, 121.

Orwell, 355-356.