[This post is the Epilogue of a series. Here are links for Part I; II; III; IV; V; VI; and VII.]

We come at last to the end of my American Nations series. What began as a two- or three-part story has stretched to eight. Those posts looked at the past and present—I want to use this epilogue to think about the future. What might lie in store for the American federation? Colin Woodard offers some possible futures at the conclusion of his book. I’d like to expand on those and sketch some scenarios for North America’s sovereign states.

I. Divorce and Remarriage

When you survey the deep divisions and polarization between the various ethno-nations of the United States, an obvious solution presents itself: breakup. The core problem with the American federation, as Woodard shows, is that the regional blocs settled by the different ethnic groups don’t conform to the official political map. The nations spill across state lines and even international borders. El Norte straddles the U.S. and Mexico. The Midlands, Left Coast, the Far West, and Yankeedom stretch into Canada. The people in these regions have more in common with each other culturally than with their countrymen and women in Greater Appalachia and the Deep South. The impassioned conflicts between the Blue Bloc and Red Bloc in the U.S. arises from these irreconcilable differences in ideology.

So, why not reconfigure the official map? Why don’t we just carve up the North American federations and put them back together along the lines of cultural settlement? The counties that form Yankeedom, the Midlands, New Netherland, and the Left Coast could all secede from the U.S. and immediately accede to their like-minded cousins in Canada, forming a grand Republic of the North. El Norte, likewise, could break away from both Mexico and the U.S. to form a new Republic of El Norte. Meanwhile, the Deep South, Greater Appalachia, and the Far West could jointly detach so as to create a version of Margaret Atwood’s Republic of Gilead from The Handmaid’s Tale (oh goodie!).

On paper, this idea holds a lot of appeal. As I noted a few weeks ago, the phrase #NationalDivorce was trending on Twitter in the wake of the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago and seizure of documents unlawfully possessed by Donald Trump. Many people in the various blocs are sick and tired of dealing with folks in the other. Talking to my family and friends in the Northeast and Northwest, I hear a common refrain: the system is broken, we’re too different from each other, compromise is no longer possible. Let’s just go our separate ways. By forming more homogenous nation-states, we could ensure that people within them would have greater ability to create their version of the good society. I harbor such longings myself. I’d much rather be in a political system with Canadians than with Mississippians. I visit Toronto and Vancouver and envy the clean, orderly government they have and the broader social democracy they enjoy.

It would be important in this scenario to accede to Canada—and maybe even enter a stronger alliance with the European Union—in order to maintain balance within the geopolitical system. As I’ve said before, as bad as U.S. imperialism is (and it’s very, very bad), the logical successor to our superpower status will be the PRC—and its model is even worse. I’d rather fight for socialism inside a liberal capitalist state than an authoritarian one. The Founders of the U.S. republic forged a tighter bond between the sovereign states because they feared that the world’s empires—Spain, France, Britain—would gobble up the fledgling American countries. That calculus has changed of course—it’s the U.S. that’s the empire now. I am not in favor of another century of liberal interventionism, which has left millions dead, empowered autocrats, and left the U.S. with little to show for it. And it’s also not certain that China has ambitions beyond mere regional hegemony. But regardless, if we break apart without forging a new and better federation, we’ll weaken our ability to create an international order based on cooperation and open ourselves up to foreign influence. That will make it much harder to deal with pressing problems like climate change.

It would also be essential that the new republics maintain some sort of formal ties between themselves—economic, diplomatic, political, and military. Chuck Thompson has something like this in mind in Better Off Without ‘Em: A Northern Manifesto for Southern Secession (2012), which Woodard reviewed for The Washington Monthly. As Woodard relates, Thompson envisions the following transition:

A friendly diplomatic breakup with “a series of military treaties and economic agreements that play both to southern strengths and American needs.” The two states would be tied together in a cooperative defense agreement with what sounds like a joint standing army, while open borders and existing interstate commerce laws would remain in effect “for a minimum of fifty years.” Anyone who felt they wound up in the wrong country could automatically become a citizen of the other during an extended probationary period. Thompson makes the process sound as calm and technocratic as the proceedings of the European Commission.

Along with the positive reasons for such an umbrella relationship, there’s a negative one as well: lessening the likelihood of war, especially given the aggressive posture of Christian nationalists. Along with foreign intervention, the other danger the Founders feared was rampant civil conflict inside North America. Woodard details the fractious early years of the republic in his essay “The Almost Civil War of 1789.” I’ve argued in these posts that civil war has been quite common between the American Nations since their various foundings over the centuries. The French and Indian War, War of Independence, and War of 1812 all had elements of civil wars—along with being imperial and anti-colonial conflagrations. Of course, the War of Southern Aggression from 1861-1871 springs to mind most readily when Americans hear the phrase “civil war.” Such violent conflict, far from an aberration, is to be expected between ethno-nations that have such deep divisions and argues in favor of some EU-like situation to promote peace.

It’s this bloody history that causes Woodard to balk at the idea of secession. As he relates, the Maine journalist covered Eastern Europe and the Balkans in the 1990s. In that capacity, he witnessed the breakup of Yugoslavia firsthand, with its war crimes, genocide, and atrocities. He sees many of the same dynamics at work in the United States:

We have most of the ingredients here for a nasty bloodbath: long-suppressed national grievances, religious extremists in positions of power, a militant culture (in Appalachia), an armed and poorly educated populace, a formal ethnically based caste system in place within living memory, and a history of conflict with the federation it would be leaving. Call me crazy to suggest things could spin out of control during the fractious effort to undo the federation, but remember that in 1990 alarmists in Sarajevo laughed at that concept too. My assessment of the human condition prevents me from endorsing or advocating a breakup of the United States, as convenient a solution as it might seem on paper.

America, in other words, is like a bad marriage. Nobody’s happy but the divorce could be bitter. (Omar El Akkad imagines such a dystopia in his 2017 novel, American War) And who’d get the kids? What would become of our vast military? Our overseas possessions and territories? Whither Hawaii? As Woodard points out, drawing a new map wouldn’t be as easy as you think. Many current secessionist movements propose configurations that would merely reproduce the internal divisions between the nations. And even if you followed the lines of Woodard’s map, you quickly see that the culture of Dixie stretches far north.

When you consider the reach of Greater Appalachia and Tidewater, “you’d have to say good-bye to a big piece of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Missouri, and the lower Great Lakes states, and most of Delaware, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas to boot,” as he puts it. “That’s not an amputation, it’s a vivisection.” You’ve also got the Far West carving a massive chasm between the Left Coast and Yankeedom—one that stretches into Canada. How would we deal with this? Would the Left Coast breakup further, into some kind of Republic of Cascadia? How could it access the eastern republics for business purposes and cultural exchange?

Moreover, we’ve seen how many folks in the backcountry of Yankeedom and the Midlands have allied themselves with the Southern bloc thanks to Trump. These angry, heavily armed rural residents would be a wild card in any attempt to pull them away from their allies. Likewise, what would become of Black Americans and other minorities in the Deep South should they be cut off from the North? History holds some scary answers. Perhaps a plan of voluntary resettlement, as Thompson suggests, could rescue them from the tender mercies of their enemies. But to Woodard’s point, that could get very messy very fast. The homogeneity of Europe’s nation states got that way only through staggering ethnic cleansing and deportations during and after World War II.

But there are other models, too, ones that suggest it can be done without bloodshed. Czechoslovakia, for instance, broke apart peacefully in 1993 when faced with internal tensions between its two halves. That was a small country, of course, so maybe the best analogy for the U.S. is our old foe: the U.S.S.R. and the former Eastern Bloc. Between these various Communist states, we’re talking about the largest political entity in history breaking apart into separate states with astonishingly minimal violence. The ethnic diversity within these regions matches—if not exceeds—our own, and yet they’ve mostly avoided post-separatist conflicts (the present Ukraine War being an imperial land grab, not a civil war). As Tony Judt writes in Postwar, the dissolution of the states of the Warsaw Pact was unprecedented: “No other territorial empire in recorded history ever abandoned its dominions so rapidly, with such good grace and so little bloodshed.”1 The same when it came to Russia itself.

Which brings us to the final consideration. When you read about the cases of Yugoslavia and the U.S.S.R., what becomes clear is that nothing was inevitable about their respective outcomes. The same kindling that exploded in the former was present in the latter. Why, then, did one spiral into civil war and the other didn’t? Judt arrives at an obvious, but overlooked, reason: The choices of political leaders. If Gorbachev had thought differently, he could easily have resorted to a crackdown of the revolutions in 1989, just as the Soviets had done in 1956 Hungary and 1968 Prague. In him, however, the world was blessed with a decent man and egalitarian reformer. As Judt puts it, it was Mr. Gorbachev’s revolution. Slobodan Milosevic, on the other hand, was a tyrant and a psychopath. The hell that he plunged the Balkans into was of his own making, as Judt points out:

There is no doubt that in Bosnia especially there was a history upon which Serb propaganda could call—a history of past sufferings that lay buried just beneath the misleadingly placid surface of post-war Yugoslav life. But the decision to arouse that memory, to manipulate and to exploit it for political ends, was made by men: one man in particular. As Slobodan Milosevic disingenuously conceded to a journalist during the Dayton talks, he had never expected the wars in his country to last so long. That is doubtless true. But those wars did not just break out from spontaneous ethnic combustion. Yugoslavia did not fall: it was pushed. It did not die: it was killed.2

This last point brings us back to Woodard’s warning. If the character of national leaders is what separates a peaceful political process from a violent one, then now may not be an opportune time for messing with the American federation. In Donald Trump, we have produced our own Milosevic, and his recent flirtation with incitement—not to mention his attack on the Capitol—shows that he’d most definitely light the U.S. tinderbox ablaze before conceding anything. A similar sociopathic personality, he can think only in terms of win-lose. The idea of a peaceful separation where everybody gets something they want is anathema to him, and his cult followers are itching for a fight. If the American people could come together in a popular convention (with safety measures and a good process built in) perhaps we could rearrange the continent along better lines.3 But right now, our leaders are more likely than not to send us into the internecine abyss.

II. Renegotiation

If secession is too risky at present, might there be other alternatives before us to improve our national condomenium? After all, it’s not just that our map is bad—it’s that the Constitution fails to bake ethnic divisions into our political system, the way it does in power-sharing arrangements like Northern Ireland and Switzerland. So, can we imagine some better arrangement within the current borders of the United States? If we could rewrite the Constitution, what could the U.S. put in place to handle the intractable conflicts between the American Nations?

Redraw the Map

Whatever else we do, I think we should at the very least redraw the state borders within the United States, making them cohere with the patterns of settlement and regional divides. The new borders would look something like the above (pay attention to the colors, not the lines). You wouldn’t necessarily have to make seventeen states, as indicated there. You could break some of them up into smaller units, e.g., upstate New York + New England could become East Yankeedom, while the Great Lakes region could be West Yankeedom. Likewise, you could splice Greater Appalachia into Upper and Lower states, split by the Mississippi. But the goal would be the same: internally uniform provinces, instead of the balkanized ones we have now. They’d be some weird looking states, but not any less than the arbitrary lines we’ve drawn now. And it could create greater stability within them and make it easier to represent the views of the American Nations. So, how would these reconfigured states relate to each other and the national government?

The Confederation of American States

One option is a variation of the European Union idea proposed earlier. Here, the U.S. would essentially revert to the form of government it had under the Articles of Confederation. Sovereignty would devolve to the new states, who’d maintain an overarching alliance for the purposes of national defense, monetary policy & trade, and foreign affairs. In other words, the present E.U. David French proposes something like this in his book Divided We Fail (2020). By devolving power to the states—reconstituted along ideological lines—we could let people work out their own society with like-minded souls, while maintaining the economic and military benefits of confederation.

The problem with French’s approach is that our current federalist system has ruined us—more decentralization could just make matters worse. In The Divided States of America (2020) Donald F. Kettl argues that federalism breeds inequality, incompetence, and gridlock. While it allows folks in homogenous communities to get their way more easily, it proves a disaster when dealing with continental or transcontinental issues. Think of the pandemic, for example—American federalism made it impossible for the national government to respond to COVID-19 with universal, coherent, effective public health measures. Each state, each county, each city had its own rules. This led to chaos and mass death—a virus doesn’t respect borders. Likewise with climate change. Global warming is an international problem that requires a unified solution by every country. We make that even less likely if we allow regions like the Deep South more leeway to thwart environmental legislation and pollute the Earth.

The People’s Republic of America

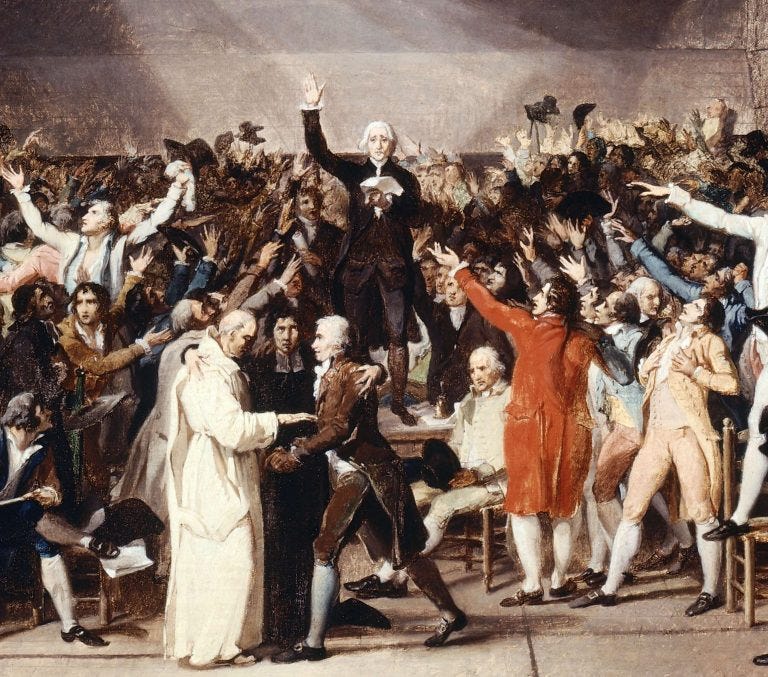

The other option—and the one I entertain the most—is to move in the opposite direction: to abolish provincial governments and create a unitary state. In other words, end federalism by centralizing authority at the national level. Here I have in mind what the revolutionaries achieved in France in the 18th century. The Revolution brought the country into the modern age by dissolving the parlements and other archaic features of the ancien regime. They took the tangled web of districts, dioceses, and provinces and brought about order by redrawing the map into coherent Regions, Departments, and Arrondissements.

In such a model, the new republic would still have the reconfigured states, but they’d function as administrative districts, with far less authority vis the national government. As Lisa Miller argues in Boston Review, we can have a decentralized system within a unitary state, the way the United Kingdom and France do things. We could maintain state legislatures, if we wanted, but greatly circumscribe their mandate, ending federalism.

This would allow the central government greater ability to build up the nation. No more NIMBYers suing a High-Speed Rail Network into oblivion. No more rogue governors undermining the CDC during a public health emergency. The national government could actually execute its will in a rational way across the country and deliver the kinds of universal public goods and services our friends enjoy in other Western countries. “A unitary system could define national standards,” Miller says “decentralize implementation, and even carve out specific areas of authority for the states.” She goes on:

If the goal is to get the national government to ensure coordination and harmony of social policy, it hardly seems ideal to have a system where the scope of national authority can be regularly challenged by opponents of coordination and harmony—a system, that is, rife with veto points. A relatively high level of decentralization might be useful for implementing a national response, but it’s not clear why a federal system of any kind is necessary—let alone the messy, constitutionally contested American version.

I know what you’re thinking: wouldn’t this breed more conflict between the American Nations? How could a unitary state deal with the cultural divides between the various regions, without just bulldozing through them? I may like such a government if it’s run by people with my beliefs—but what if my enemies get control, and impose polices on the entire polity that I detest? What then?

Hear me out. If we did move in such a unitary direction, I’d insist that we make such a state a real democracy. That is, make sure its legislature accurately represents the views of the citizenry and build in features to ensure that one regional bloc can’t dictate its will to another the way it does now. For starters, I’d introduce a multi-body legislature of the kind I’ve mentioned before (though perhaps a modified version to start that would combine both sortition and elections). The first chamber, the Agenda Council, would consist of 150 citizens chosen by lot to set broad policy goals.

The middle chamber could take the current House of Representatives and expand it to the cube root of the national population (in our case, something like 650 members). We could then break up the two-party duopoly and create a bunch of new political parties, one for each ideology of the major American Nations: Social Democrat (Yankeedom); Liberal (New Netherland); Conservative (Tidewater); Nationalist (Deep South); Libertarian (Greater Appalachia); Communitarian (Midlands); Populist (Far West); Christian Democrat (El Norte); and Green (Left Coast). These nine parties could compete either within the new states (divided into multi-member districts, utilizing ranked-choice voting) or beyond them on a national level, with seats allocated based on the proportion of the popular vote each party receives.

Once gathered in the new Assembly of Citizens, the parties would not be able to establish permanent control over the chamber. No more parliamentarianism, where two or three parties form a coalition to dominate the floor and dictate the flow of business. Rather, the chamber would remain neutral, awaiting a remit from the Agenda Council. Once it arrives, the parties would each have an opportunity to produce their own policy proposals in accordance with the mandate. Each caucus could do research, take testimony, solicit input from experts and think tanks, hear from their voters, etc. Then, they’d all bring their drafts to the floor. A period of deliberation would ensue, in which the parties would have to achieve a coalition around an actual bill—they’d have to work together to combine, alter, and rewrite proposals into a policy that garners a majority of the representatives in the chamber.

After they pass the bill out of the Assembly, final adoption would be taken up by a Policy Jury. This panel of 500 citizens would conduct a trial of the bill, with proponents from the Assembly arguing in its favor, and opponents arguing against. A bench of three judges could oversee the trial to ensure impartiality and fairness. The Jury could submit questions, but would not deliberate. Rather, at the end, they’d take a vote by secret ballot. If they achieved 60% plus one, the bill would pass. If not, it could be returned to the Assembly for revision.

The advantage here is four-fold. First, the use of lotteries would ensure that the three chambers would accurately represent the makeup of the population—the legislature would really be society in miniature. Secondly, the parties would be organized around the ideologies and even boundaries of the American Nations, channeling their views more clearly and coherently. Thirdly, by forcing the parties to work together bill-by-bill, it would encourage them to come up with legislation that takes into account the various regional identities in the process. Accommodations for each Nation could be worked into a given bill, rather than one bloc foisting its entire program onto the other. Finally, the ultimate decision would rest with everyday people, giving them the opportunity to veto any proposal that goes too far and hold politicians to account.

At the same time, the National Legislature would be able to exert its authority over the whole country—it wouldn’t have its decisions mucked up, hijacked, and nullified by the states. (And in case you’re afraid that this is the road to serfdom, recall that in the United States, historically you’re much likely to be tyrannized by your state or local government than the national one. The latter, in fact, has often been the only guardian of civil rights and personal liberty against the petty tyrants and mobs in your backyard.) Thus we’d achieve a national government that’s at once more democratic and more centralized—more attuned to the identities and values of each region, yet also more empowered to establish effective, logical, streamlined government.

You’ve heard my ideas about the judiciary before, so I won’t rehash them. But we could do something similar with the Executive in this new arrangement, chiefly by moving from a unitary to a plural one (examples include Switzerland; and Pennsylvania circa 1778). Imagine an Executive Council of nine members, one each chosen by lot from candidates submitted by the nine parties. The chair of the Council could rotate, as would its members, who’d each serve three-year terms before cycling out permanently. This would ensure that each ethno-nation is represented on the Council, and would force its members to achieve consensus (or at least a supermajority) in making decisions.4

III. Conclusion

These are just a few possibilities that lie before the American Nations. There are many more—variations of the models I’ve put forward, and others that go in directions I can’t imagine. Who knows what creative ideas people could come up with when brought together in a spirit of curiosity, good will, and mutual understanding? It’s impossible to predict in advance, because the whole idea of democracy—people actually determining their shared lives—is that you can’t dictate what the results will be. But with awareness of the identity, values, and stories of the American Nations—and a fair, representative, informed process—we may just make the next five centuries of this strange, beautiful continent and its fascinating peoples better than the first.

Tony Judt, Postwar (New York: Penguin, 2006), 633.

Judt, Postwar, 685.

Here I have in mind a three-stage constitutional convention via democratic lottery as outlined by Terry Bouricius.

The Head of State could be separate from the Council and could also be plural. In this case, I imagine three members forming the Head of State, chosen by lot from a pool of vetted candidates, each one from a different American Nation (or, that is, a different ideology). They’d serve longer terms to encourage stability (maybe six years, like today’s Senators), with one rotating off every two years. They’d then be replaced by a member from a nation next in line, so that the Head of State would pass collectively through all nine nations equally. We could arrange the succession such that at any given time there’d be an even split between left (Social Democrat, Green, Liberal); right (Conservative, Nationalist, Libertarian); and center (Christian Democrat, Communitarian, Populist). This is roughly based on today’s Head of State in Bosnia, a plural Presidency that contains one Serb, one Croat, and one Muslim at all times.