My Abortion Journey

Becoming a Pro-Choice Christian

As a Christian who cherishes human life, I understand those who think abolishing legal abortion is good. I’m a former Catholic who thought seriously about becoming a priest. I hold a Master of Divinity from a Catholic institution, where I studied moral theology. I know the mindset of its milieu from the inside. Many anti-abortion activists have convinced themselves they’re saving lives. And who doesn’t want to do that? If you think you could be on the side of good—and God—by saving lives, who wouldn’t feel attracted (or pressured) to embrace that cause?

Those who want legal abortion access also think we’re saving peoples lives—poor women. But our side, I’m afraid, has done a bad job of marketing by framing abortion as about choice. While correct on principle, choice is a word associated in daily life with consumer habits and careless, half-baked, impulsive acts. Coke or Pepsi for lunch? Hmm, Coke! Have a baby or abort? Hmm, abort!

This is the troubling image conjured by choice in the minds of anti-abortion activists. It sounds like you’re degrading human life into a commodity. It raises fears of a slippery slope to eugenics, a throwaway culture where the elderly, people with disabilities, and other vulnerable populations are stripped of their dignity. Some, if not many, anti-abortion activists want to protect those people, made in the divine image.

But so do people who favor legal abortion access—more than a lot of anti-abortion advocates, especially white evangelicals. The states that allow abortion have the broadest social supports for the poor in the nation—those now banning it, the weakest. Most states outlawing abortion also execute prisoners with ruthless abandon. Those with abortion do not. Where is the epicenter of the new abortion regime? The Deep South—the historic site of slavery, Jim Crow, and sodomy laws. This belies the truth of their actions: that it’s about power, punishment, and control—not life.

Choice also paints women as careless and indifferent to the moral stakes of sexual intimacy, pregnancy, and termination. But that is untrue. Women do not approach abortion like a consumer habit at all. For them, it is a fraught, profound decision. It is about care for their bodies, their lives, and often their other children. It is not a thoughtless disposal of human beings.

The anti-abortion movement has been very psychologically powerful in this regard. I myself wrestled over abortion for years. Like many Catholics, I grew up in an ecclesial culture steeped in traditionalism. In this nostalgic vision, abortions never used to happen. Women led wholesome lives in idyllic families, raising children and mothering them with affection while husbands labored at the office. This fantasy was, of course, totally at odds with my home. My parents led modern lives, a marriage of equals with both spouses working.

But in the imagination of the Catholic hierarchy, abortion—like feminism itself—is a dangerous invention of modernity, akin to industrial pollution. This road to perdition burst on the scene—along with contraception, gays, and sex itself—in the 1960s, that era of decadence. Philip Larkin parodies this mental construct in his poem “Annus Mirabilis”:

Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three (which was rather late for me) / Between the end of the "Chatterley" ban / And the Beatles' first LP.

It’s all a myth. Women have sought to terminate pregnancies since the dawn of time. And when it comes to “tradition,” human beings lived for hundreds of thousands of years in hunter-gatherer bands, egalitarian societies without fixed gender roles. Women harvested food and men hunted, but all were involved in providing for the community’s sustenance. Childrearing was done communally, allowing kids to play freely and benefit from “alloparenting.” The idea that it was solely women’s work was absurd. In indigenous American cultures, like the Iroquois, women held political power—the men could initiate war only at their behest. What’s more traditional? Their way of life? Or 1950s suburbia? Measured against the long arc of human history, the nuclear family, with a sole male breadwinner, is the novelty, not the norm.

Even in the Anglo-American world, pregnancy termination before “quickening” (the time when the mother felt the fetus moving in the womb) was legal under common law from 1607 until 1828. According to the American Historical Association, abortion laws emerged slowly starting in the early 1830s, mostly to protect women from dangerous procedures—not the fetus. In the 1850s, a mysogynistic physician named Horatio Storer spearheaded a campaign to ban abortion as a means to put women back in the home and combat the rising immigrant (read, non-WASP) population. This was a response to first-wave feminism (a part of the antislavery movement), as women advocated for property rights, education, and the vote. By controlling their reproduction, these chauvinists could thwart their burgeoning agency. By the 1860s, complete abortion bans were on the books in twenty-six states. Those laws were the aberration, not abortion. And it still remained legal before quickening in eleven states.

I was unaware of this history as I went off to college at Holy Cross in 2002. The sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church had broken the previous winter, an ominous start to my studies. I wasn't particularly motivated by abortion. But like many young people, I was looking for meaning and became devoted to my faith. I got involved with a conservative group of students, who were militantly anti-abortion. That much I sympathized with. But their homophobia—of a piece with their abortion views—disturbed me. It was a warning sign.

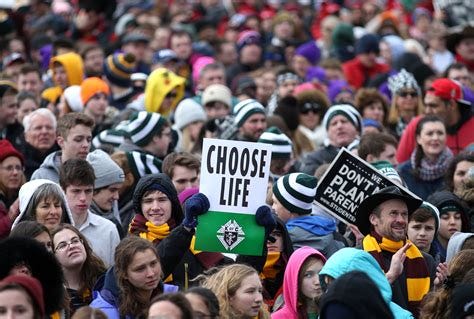

Nevertheless, I attended the March for Life in D.C. my first year. I went in support of many “life” issues, especially abolition of the death penalty and war. Yet as I marched, the gruesome, distorted, pornographic pictures carried by anti-abortion zealots surrounded me on all sides. Young people always make for the most committed shock troops—that’s why revolutionaries and the military recruit them intensely. Their tactics of guilt and panic disturbed me. I heard almost nothing about the poor from their lips. Later, I learned that the images on those posters were doctored for maximal outrage. I never returned, and kept my distance from that faction ever after.

As I advanced through college, I became increasingly progressive and spent my time with the social justice students who made mission trips abroad and worked with the poor in Worcester. I came to disagree strongly with the church’s teaching on gays and lesbians, especially after a close friend—who is now a priest—came out to me our junior year. When the conversation turned to abortion, I, like many liberal Catholics, was uncomfortable with the church’s teaching. But we kept quiet. The law of the land was settled, we thought. Roe lulled us into a false sense of security. We never imagined it could be overturned. So, why make a fuss?

This conspiracy of silence continued in my divinity studies. My school was a center-left institution, with a top-notch faculty and bright, liberal students. Many, if not most, students had serious qualms with the church’s teaching on abortion—especially the women. The issue was almost never discussed, and when it was, it produced discomfort and pained expressions. But few dared voice these objections. Abortion is the third rail in Catholic circles. Many liberals crucify their feelings and pay lip service to official teaching or remain silent, lest they face ecclesial scrutiny.

When the topic came up in my moral theology course, I, like most, took it seriously and with an appreciation to its complexity. Yet I got a taste of the reductive monomania of abortion foes: a classmate (a woman) expressed disbelief when our professor (a priest no less) instructed us that the church does not consider the termination of an ectopic pregnancy to be a direct abortion. She was so committed to the idea of fetal life that she challenged him before everyone, quite emotionally. This precipitated a heated exchange that left the rest of us on edge, and relieved when we finally moved on.

The turning point arrived when I met my wife. When it comes to children, she possesses a spiritual connection with them I’ve never seen before. I joke that she’s a child whisperer, but it’s true. Children are instinctively drawn to her, feeling safe, loved, understood. Her dream is to found an early-childhood school someday. Anytime we pass a family on the street, the little ones stare at her and smile. Once, at a block party, a little boy—a perfect stranger—threw his arms around her as if she was his best friend. No matter how shy, every child we meet inevitably warms to her (and runs from me). It’s uncanny.

And yet, my wife’s deeply committed to legal abortion access. This threw me. How could she square her compassion for children with being pro-choice? And then I learned the stories of her and her friends, stories that I—a privileged male—had never heard. Of crisis pregnancies, broken homes, abusive boyfriends. When she was still in high school, a classmate got pregnant. Scared, alone, she sought out my wife for help. And so these two young girls had to make the awful decision of what to do. Her friend decided to terminate. My wife walked her to the clinic, pushing threw throngs of protestors spewing vitriol at them, flashing the same ugly signs I saw at the March for Life. It was traumatic.

These tales punctured my cognitive bubble. Like many people conditioned to oppose abortion, I lacked experience with real ethical situations—let alone the complexities of pregnancy. I began to see that there was no contradiction between my wife’s love of children and her belief that women—and married couples, for that matter—should be allowed to terminate pregnancies. No one in my life knows better about child care, pregnancy, and women’s struggles (especially their harassment and assault at the hands of men) than my wife. And she told me adamantly that abortion is not about ending a life. She’d be the last person on earth who’d harm a child.

Yet on a theoretical level, abortion still troubled me. Every time I thought about the issue abstractly, I got tripped up. Does terminating a pregnancy terminate a life? The question, the few times it came up, gnawed at me. Even as late as last summer, I struggled with abortion ethics. And then I heard an interview on The Ezra Klein Show that broke through. Kate Greasley is a law professor at the University of Oxford in the U.K., where she studies, among other things, the legal and moral philosophy of abortion. She’s the author of Arguments About Abortion: Personhood, Morality, and Law, and co-author of Abortion Rights: For and Against alongside Christopher Kaczor, a philosopher who opposes abortion.

While Greasley ultimately believes in the right to choose, she does a remarkable job of carefully and fairly considering all the arguments, contradictions, and nuances of this issue. As she rightly puts it, the real question with abortion is personhood—not life. Is an embryo or a six-week old or twenty-five week old fetus a full human person, of the same moral standing as born people? If so, yes, it would be impermissible to terminate its existence without just cause.

It’s very appealing to think of “conception” as the start of personhood: it banishes complexity, removes doubt, instills Manichaean certainty. Such black-and-white thinking comes as psychic relief to anxious minds trying to make moral sense of a baffling world. But to drive home the problem with this view, here’s a thought experiment Greasely poses that helped me achieve clarity:

You’re in a burning hospital. You have the chance to save either five embryos, or one day-old infant girl. Which do you save from the flames?

Unless you’re self-deceived, a deep-dyed partisan, or a sociopath, you probably answered the infant. And that tells us something. If embryos are full persons of the same status as post-natal people, then anyone who answers “I’d take the infant” (which is almost everyone) is a moral monster. So maybe we're not. Maybe our instincts are correct, and there is a categorical difference here. Otherwise, the millions of natural miscarriages that occur every year would amount to the greatest catastrophe known to humanity. We’d be pumping every resource into stopping it, given that it’s the death of millions of our family members. We can do some things to prevent miscarriage, but we recognize a limit. Again, does that mean we’re moral monsters?

It’s instructive that while we get rightly sad over early misscarriage, we don’t react the way we do to the death of a born child. Obviously, the closer we get to birth heightens the loss of the pregnancy—a late miscarriage or stillbirth is wrenching. But that’s the point: the stage in pregnancy matters. I’ve several friends who’ve miscarried early. It’s always a sad, mournful time, as much for the loss of what could’ve been as for what was. Yet a late miscarriage is even harder. And a stillbirth is utterly gutting. When I was a hospital chaplain, I counseled a woman who had a stillbirth. It was shocking and she was distraught. What was supposed to be joyous was tragic. All to say, again, that pregnancy is difficult and birth a miracle.

Let’s think it through. Cellular animation in its earliest, nascent, primitive stages is at work in sexual reproduction. All of us “start” as an embryo. How else would we get here? But even this statement is misleading. As Yale professor Robert Wyman describes in this lecture, biologists don’t speak of a “beginning” to life, a “moment” that starts a biographical straight line. Rather, reproduction is a cyclical process—science talks of a “circle of life.” The gametes that unite during sex are already animated—human life is not creatio ex nihilo. As Wyman says, the real beginning to human life was 4 billion years ago with prehistoric microbes.

So, right off the bat, science debunks the simplistic construct of anti-abortion advocates. In fact, the Bible itself doesn’t depict “conception” as the start of personhood—in Genesis, God makes the adam fully formed from dust. What does Christmas celebrate? Christ’s nativity—the Annunciation is minor in comparison. In rabbinic teaching, Wyman points out, human life was not thought to start until birth—literally, when the baby’s head exited the birth canal.

No culture on Earth celebrates “conception day” that I am aware of. They all mark birth as the profound entry into this new existence. If there’s someone out there who’s added nine months to their legal age, I’ve never met them. I’ve read dozens of biographies in my time. Not one begins with a description of its subject forming in the womb. Are historians deficient in neglecting to narrate those first nine months? No—that would be absurd. Again, this is telling.

So, does personhood start at birth? Not necessarily. Greasely thinks so—at birth, massive cognitive and physical advances occur in the baby, far beyond anything that happens before. We enter into wondrous relationships with others and the world. The state provides us with an official certificate of birth, which marks our legal existence. But Greasely also admits that reasonable people can disagree on this—the answer is a mystery. As another helpful heuristic, she employs the metaphor of the heap. If you take grains of sand and pile them up, eventually you go from nothing to a heap. But when did it precisely turn into said heap? The millionth grain? One more? One less? At some point, it happens. But where exactly is impossible to say. So with personhood.

That’s why the last thing we want is to have the state empowered to investigate this complex ethical decision—made in the sanctity of one’s conscience—and prosecute people. Imagine being a pregnant couple faced with an extremely premature labor. You have to decide whether to use extraordinary invasive measures to save the fetus, with no guarantee of success, or let it pass with dignity. I don’t have to imagine such a scenario—it happened to people I know: moral, loving, committed Christians who have several children. Now, can you fathom having to make that decision in fear that you, or your medical team, could be charged with criminally negligent homicide? These situations will arise with great frequency under the new abortion regime and will exercise a chilling effect on us all.

I don’t wish miscarriage on anyone. And I don’t wish unwanted pregnancy or abortion. I wish every pregnancy was wanted and our social supports excellent enough for poor women to have as many children as they wish, with the option to terminate if, in the end, they so decide—the way it’s handled in Europe, Canada, and most of the West. The primary reason given for abortion by women seeking it is socioeconomic. A majority already have a child and want more. But they’re crushed by overwork and a lack of social support in our grossly capitalistic, massively unequal nation. And when it comes to the Deep South—where the most draconian abortion laws are now going into effect—the women who will suffer most are Black. That’s why 68% of Black Protestants do not support the overturning of Roe. They know these laws seek to bring about what the Deep South has wanted since 1670—total control of its Black population.

Abortion does not facilitate murder. It does facilitate women’s full, equal participation in society, while balancing that interest with safeguarding human life. When it comes to this difficult issue, the best we can hope for in a diverse, modern, pluralistic society is a sound, judicious compromise. And here’s the thing: that was the very compromise that Roe and Casey reached and which has now been abolished by a partisan judicial junta (for a real democratic approach to the issue, by the way, Ireland provides the best example.)

I’m still a practicing Christian (an Episcopalian now). I try to love God and love my neighbor. And because of that, I am pro-choice. I am pro-choice because I am pro-life. The Sunday after Dobbs was handed down, I joined members of my parish and wrote notes of support for women waiting for procedures at the clinic down the street. I can’t imagine what they were going through in that moment, but it felt good to let them know that our community stood in support of them—their freedom, privacy, and dignity.

As should all Christians. Of the 31,102 verses in the Bible, precisely one mentions pregnancy termination—a law against a man attacking a pregnant woman to make her miscarry. In other words, not an abortion as we understand it. In his entire earthly ministry, Jesus of Nazareth was silent on the matter. If abortion is murder—a hundred Holocausts in the eyes of its foes—why did the Incarnate Word of God never speak of it?

Christ, in fact, was a radical feminist, upending the gender conventions of his patriarchal culture. He associated with prostitutes, was ministered to by women, and at the Resurrection appeared to Mary Magdalene before any other disciple. When the scribes and Pharisees caught a woman in adultery—a violation of their purity code—he refused to condemn her: “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” By contrast, he had harsh words for lawyers:

Woe also to you experts in the law! For you load people with burdens hard to bear, and you yourselves do not lift a finger to ease them.

I’m not sure what Jesus would say to the Supreme Court today. But they should read his words with fear and trembling. Soon, the tables will turn, and they’ll be under Judgment.

Very close to my own journey of becoming a “pro-life” supporter of abortion rights. My wife and I endured 2 miscarriages and a stillbirth — along with giving birth to 2 healthy kids. When our first son died in the hospital 30 minutes before being “born,” that was the worst day of our lives. An early miscarriage was sad. A later miscarriage, leading to a D&C (also common in 1st trimester abortions) was harder. Neither compared at all to a miscarriage. So, while abstract conceptions of when life begins may be a valid part of a moral argument, for me, they do not pertain to real life situations.