Subversive Savior

The Jesus Agenda

I. The Return of the King

The Jews of Jesus’ day, like their ancestors, understood their political domination by Rome in terms of Israel’s deep story. As in Egypt, as in Babylon, the people had fallen into captivity. This was a consequence of their failure to live the covenant, to create the just society God intended. And as in those days, they longed for deliverance—for Yahweh to return as king, forgive their disobedience, and lead them out of bondage. This was their eschatological hope: not for the end of the space-time universe, but for the real end to their exile. To accomplish another exodus, Yahweh had to overthrow their imperial overlords. As with Pharaoh, the Lord would do this through a decisive historical event—God would fight the liberating battle here and now. Israel would truly return to the land, free and living in right relationship with each other and their god.1

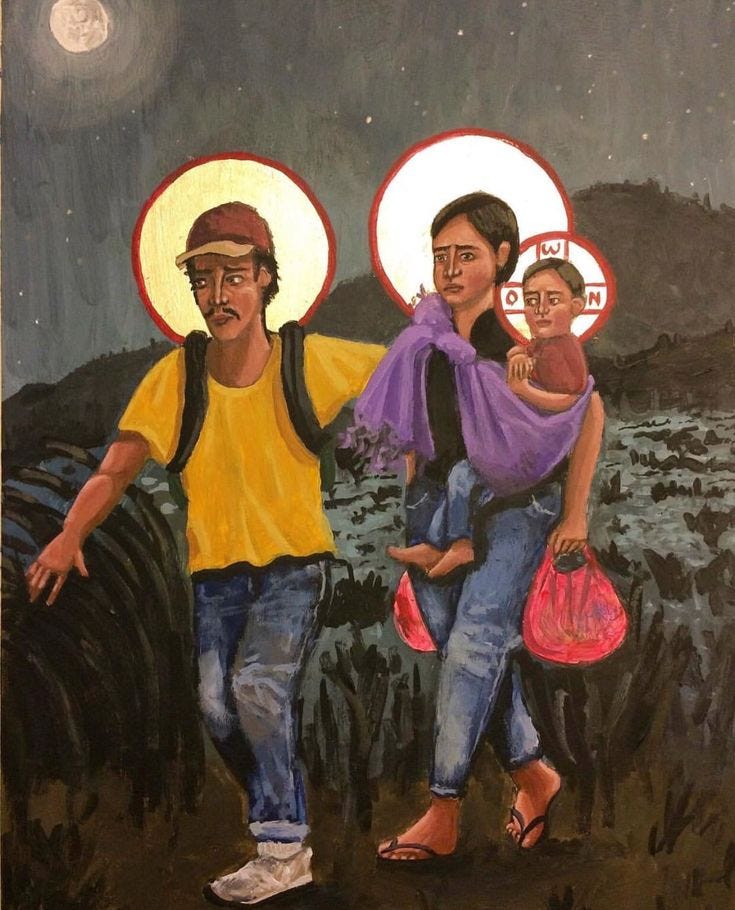

It was into this social dislocation—and the meta-narrative which framed it—that Jesus emerged. He who hung the heavens and the earth chose to become incarnate not as an emperor or warrior or genteel patrician. No—as a landless peasant he came, under foreign control in a forgotten corner of a despised region at the lonely edge of a far-flung empire. He was born in 4 BCE in the final days of Herod the Great, to a teen-aged girl who’d become pregnant out of wedlock. Forced to journey far from home for the imperial census, she gave birth in a barn. No sooner had his parents recovered from this indignity than they had to flee their tyrannical ruler’s bloodlust and become refugees in a foreign land.

Upon their return, the boy grew up in Nazareth, a Galilean backwater of some four-hundred souls. Jesus was a worker: both he and his father were handymen, jacks-of-all-trades, “poor men from a poor family,” says Edith Rasell. They’d likely lost their land in a previous generation through debt and foreclosure. As laborers, they earned about a denarius a day, just enough to keep their heads above water. Jesus probably couldn’t read or write; only about three percent of the population did, and they were among the aristocrats and scribes. The Word of God was illiterate, living and moving within an oral culture. Yet he possessed more wisdom than all think tanks and white papers combined.2

At a certain point, Jesus left home and became a follower of John the Baptizer. John’s father, Zechariah, was a member of the upper priestly caste in Jerusalem. But he turned his back on the Temple system—the world of his father—and becomes the original hobo hipster. Into the wild he went, preaching a message of collective change. This pronouncement—telling people they’d be renewed through his ritual, not the Temple’s—was, as N.T. Wright says, “clearly, ‘political’ as well as ‘religious,’ partly in that Herod Antipas may well have been a prime target of John’s invective, but also because anyone collecting people in the Jordan wilderness was symbolically saying: this is the new exodus.” He was replacing the Temple, replacing Israel itself.3

John believed God was soon to bring about Israel’s ultimate rescue through a new figure, whom he preceded. Imagine people’s shock, then, when Jesus split off and made a still bolder announcement: the Kingdom of God is here. Yahweh’s returning now, at this very moment. And he—Jesus—stands at the center of this activity. “The Kingdom of God” wasn’t a vague phrase with some general religious aura. To a 1st-century Jew, God’s reign meant the vindication of Israel, victory over the pagans, the gifts of peace, prosperity, and social justice. If he heard anyone talking about the reign of Israel’s god, he would assume it referred to this hope.4

So when Jesus announced the Kingdom, “the meaning was not escapist or dualist,” Wright says, “but revolutionary.” If Yahweh was leading the people into his kingdom, as the Nazarene proclaimed, it meant they were being freed from autocrats. “The means of liberation were no doubt open to debate,” Wright says. “The goal was not.” And when that happened, “the whole world, the world of space and time, would at last be put to rights.”5 It wasn’t about a private, interior, ‘spiritual’ experience. It was about the oppressive social order being overturned:

The phrase carried the particular and definite revolutionary connotation that certain other people were due for demotion. Caesar, certainly. Herod, quite probably. The present high-priestly clan, pretty likely. When Yahweh was king, Israel would be ruled properly, through the sort of rulers Yahweh approved of, who would administer justice for Israel and judgment on the nations...The idea of the true god being king was tied in with the dream of holy revolution.6

II. Vanguard of the Revolution

Jesus carried this convulsive message from village to village, avoiding cities. He thus fit the vocation of prophet, in the style of Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Elijah. But we should understand him as “more like a politician on the campaign trail than a schoolmaster,” Wright says. Far from being an “evangelist” or mere teacher, Jesus issued a public invitation for everyone to rally round his flag. In this, he was akin to the founder of a revolutionary party who beckons all to join. He retold Israel’s deep story in a provocative way: his own career, he claimed, was the turning point of the drama. This spelled treason. Herod Antipas, after all, loomed large. “People who attempted to set themselves up against that family,” Wright points out, “tended to come to a bad end.”7

The key part of Jesus’ invitation was repentance and forgiveness of sins. This wasn’t an altar call by some moralist, or a demand for individual cleansing. Jews could get that anytime they wished through the Temple rites. Rather, like John, he was calling the nation to change its historical course, to turn around, to abandon one path and get on God’s right road. “What Jesus was offering,” Wright explains, “was not a different religious system. It was a new world order, the end of Israel’s long desolation, the true and final ‘forgiveness of sins’, the inauguration of the kingdom of god.”8 Since the people interpreted the tyranny of Rome as a consequence of disobedience, to announce the forgiveness of sins was to declare liberation from their enemies, foreign and domestic. It was “a political call,” says Wright, “summoning Israel as a nation to abandon one set of agendas and embrace another.”9

To believe in Jesus, then—to have faith—wasn’t to accept a deposit of doctrines; or assent to a theory of “salvation;” or undergo some transcendent experience. It was to be convicted that Israel’s god was acting climactically in Jesus’ career and person.10 And to join up. “Jesus was urging his compatriots to abandon a whole way of life, and to trust him for a different one,” says Wright. “To say that this makes for a ‘non-political’ Jesus is to miss the vital political overtones of the kingdom-proclamation.”11

Jesus knew the powerful would refuse his call for systemic change. This intransigence grieved him, for it spelled doom. A violent insurrectionary movement was gathering steam in reaction to the colonial occupation. Militant nationalists, in league with elites, desired a war of rebellion. In Jesus’ mind, this would play into the enemy’s hands. To wage a crusade against the Empire was just a different kind of collaboration—it was adopting the methods of Caesar. However justified, it was cooperation with evil, yet another failure to live as a righteous people. More importantly, it wouldn’t work; Rome, he knew, would win. The Temple would be destroyed and the people dispersed. The apocalypse wouldn’t be a cosmic meltdown but a historical event, in the form of legionnaires. Yet those who followed the way of Jesus would escape. The deliverance of his community would vindicate him.12

“Christ for President,” Wilco, lyrics by Woody Guthrie. From Mermaid Avenue (1998)

And what a community it was. Though the elites by and large refused, the poor and outcast came in droves. To be labeled “sinners” was to occupy the lowest caste of society, the untouchables. It was these deviants—prostitutes, tax collectors— who made for Jesus’ new Israel. Christ didn’t endorse “traditional family values.” Quite the opposite: he taught that one’s real family was the voluntary community he was building—he even publicly broke with his relatives. This was offensive in the extreme, especially in his time. What’s more, his fictive family welcomed everyone: it had no borders, no walls. He found followers among the Samaritans, the hated “resident aliens.” He let women into his company and took their side against violent misogynists. In doing so, he minimized purity codes and broke patriarchal norms. He even dubbed a centurion—the tip of the Roman spear—his most authentic follower. Most symbolically, he opened his table fellowship to all, throwing God’s banquet for the “lesser sort.”13

This family was marked by a key trait: renewal of heart. Jesus’ followers were to practice the reciprocal relations of kinship that had animated democratic Israel. His intention, then, was to create a network of cells whose members would imitate his social practices. They were to lead a communal, counter-cultural way of life, relinquishing private property and redistributing resources based on need (which they continued after his resurrection). These were egalitarian, horizontal circles. Any leadership roles were to be loose and dedicated to service, the “greatest” acting as the “least.” Jesus’ way wasn’t about individual ethics, or withdrawing into eremitic solitude. Such a community already existed, at Qumran. No, his followers were to resist the oppressive political economy from the inside, building God’s new society within the shell of the old. They were to transform the political order from the bottom up, as the smallest seeds grow into the greatest shrub. His challenge, Wright says, “demarcated Jesus’ people as a community, scattered through various villages, maybe, but a community nonetheless.”14

Jesus, to be blunt, inaugurated a cultural revolution. And more than that—much more. To persuade even small groups of people to change their behavior as he intended posed a serious threat to the regnant regime. And his cry that they take up their cross daily showed the extreme demands he placed on would-be followers: total commitment, unto death. In ways exciting and scary, this was a cult of personality, engaged in a program of massive, passive civil disobedience that shook the status quo. Wright sums up its political implications:

Jesus, like other founders of movements in his day, apparently envisaged that, scattered about Palestine, there would be small groups of people loyal to himself, who would get together to encourage one another, and would act as members of a family, sharing some sort of common life and, in particular, exercising mutual forgiveness. It was because this way of life was what it was, while reflecting the theology that it did, that Jesus’ whole movement was thoroughly, dangerously, ‘political.’ […] A summons to risk all in following Jesus places him and his followers firmly on the map of first-century socially and politically subversive movements. Insofar as it also indicates a ‘theological’ meaning…this is found within the history, not superimposed upon it from outside.15

II. The Prophet’s Platform

Like every revolutionary leader, Jesus taught his adherents a set of concrete rules to live by and strategies to achieve their goals. His moral teachings were an agenda for the movement to put into practice, and commanded a robust social ethics:16

Love of God and neighbor. The core task of Jesus’ community is to put God’s vision for justice before all other idols. As a nation, we manifest such steadfast love by legislating social justice and turning our swords into ploughshares. Our God-given mandate as a country isn’t to figure out who “deserves” neighborliness. As Lincoln said in his Second Inaugural, it’s to be a just and peaceful people—among ourselves, and with all nations.

Love of enemy. Jesus’ society is to overcome ancient enmity, ethnic animosity, and tribal hatreds—whether based in class, sex, race, nationality, or religious views. In a Christian nation, there is no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free, male and female; for all are one (Gal 3:28). Thus all are to share in the economy of abundance.

Don’t worry. Jesus’ society is to banish the comparison mind and status anxiety. We are to throw away the ladder of social hierarchy, which forces people to scramble and push over each other to reach the top, and instead build a table with seats for the whole family. If we strive as a nation first to bring about God’s economy of abundance, we’ll find more than enough for our personal needs.

Welcome everyone. Jesus’ society is to practice radical hospitality: to the destitute, the worker, the migrant, the disabled, the sexual outcast—all of these brothers and sisters and more. God’s reign isn’t a line in which those who just came or are in a minority must wait “their turn.” All God’s children have a seat at the table of the Lord. “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers,” reads Hebrews, “for by doing that, some have entertained angels without knowing it” (Heb 13:2). A Jesus nation, then, doesn’t build a wall—it opens its doors in welcome and embraces the nations of the world in brotherhood.

Don’t judge others. God’s society is not to judge the worthiness of people to share in its abundance. The Lord makes the sun shine and the rain fall on the evil and the good, the just and unjust alike (Matt 5:45). Who made us God, to judge others by our perception of their situation? To make social assistance conditioned on nit-picky regulations and miserly hoops? Jesus doesn’t say to the poor, “You should’ve stayed in school, held down a job, not been knocked up, gotten married, said no to drugs, kept out of jail.” Neither should we.

Cancel debts and lend freely. Jesus goes beyond the Law’s command for those with excess to loan to the poor without interest. Instead, he tells them to give without expecting any repayment at all (Luke 6:34-35). As we’ll soon see, his one prayer instructs his followers to cancel monetary debts, to practice the Jubilee Year now. They are to discard the scarcity mindset and adopt the abundance mindset. So does a Jesus society—it cancels debt and radically restructures financial systems to serve the poor, the young, the aged.

Resist Caesar, but without killing. Jesus’ answer to the question about paying taxes to Rome is cryptic and symbolic. On the one hand, it directly evokes the Maccabean revolt against the Greeks. Judas Maccabees had instructed his sons as follows: “Do to them as they have done to us,” i.e., fight the pagans and obey God’s commandments (1 Macc 2:66-68). So for Jesus to say, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s,” is to say, “Pay back Caesar what he’s owed! Render to Caesar what he deserves!” Such words, on their face, would’ve been heard as revolutionary. But he adds a twist: give to God what is God’s, i.e., righteousness, which precludes killing. Violence, to him, is just as much a compromise with Caesar as paying taxes. Jesus’ followers are to engage in neither—not conformity with the Empire, nor insurrection against it. Christ rejects religious nationalism and imperial oppression alike, seeing them as the flip-sides of the same coin. And he refused, quite literally, to carry it. Therefore, a society of Jesus rejects war, renounces nationalism, and dismantles empire.

The poor will always be with us... Few sayings of Jesus are more abused than this. It isn’t an instruction not to help the poor—when he utters it, he’s eating in the house of a leper, for God’s sake! Jesus is really rebuking his male disciples for being rude to a woman who makes a beautiful, tender messianic gesture (Matt 26:6-13). And he’s quoting here from Deuteronomy 15:11: "Since there will never cease to be some in need on the earth, I therefore command you, ‘Open your hand to the poor and needy neighbor in your land.’” People, Jesus knew firsthand, will inevitably fall into poverty through a host of reasons, most out of their control: illness, accident, abuse, their parents’ choices, unemployment, bad luck.17 Therefore, the obligation to raise up our poor brothers and sisters—which we exercise through self-government—never ends. A Jesus society doesn’t declare war on poverty, announce a few years later that it’s failed (as Ronald Reagan falsely claimed), and throw up the white flag—all while cutting taxes for the rich. Like Jesus, a godly nation keeps up the effort until every lost sheep is brought home.

Wealth is wrong. Jesus wasn’t an ascetic; in the Gospels, he likes to party, go out with friends, and even dine with elites. He enjoys the company of rich people, to the point of love. But he’s uncompromising about the evils of money. He makes no distinctions about the source of one’s wealth. He doesn’t justify it by “merit” or “hard work” or “ingenuity.” The social resources of the nation are for the common good, meant to be managed and deployed to promote the general welfare—especially of our weakest brothers and sisters. To amass personal bounty, however gained, is to hoard others’ resources. It’s theft. Jesus doesn’t call his followers to destitution, but he does condemn the rich—the millionaires and billionaires of his day—without reservation. In his parables, he points out that they’re too concerned with accumulating treasure and hoarding it in tax shelters to come to God’s banquet. This bars everyone—especially themselves—from participating in God’s reign.

Far from a sign of blessing (as many in his day believed, and ours) storing up wealth—as an individual and as a nation—is, to Jesus, idolatry. It’s not about being inwardly detached from our loot. The very possession of riches, while others’ needs go unmet, manifests our attachment. It reveals that our hearts are stony, that we’re enslaved to the false self, placing our sense of worthiness not in our relationship with God, our creator, but in stuff. What does it say, then, when a nation makes economic growth, GDP, the ultimate benchmark of success and not the well-being of its people? When it hoards greater wealth than any empire in history yet has a more poor people per capita than all developed societies on earth? It says that such a nation has prostrated itself before Mammon. It shows how little it loves the Lord and his people, how much it chooses the idol of Empire over the god of the Kingdom. If we, as a country, wish to enter the latter, we must do as Jesus teaches: buy this pearl of great price by, paradoxically, redistributing our national surplus and giving it to the poor inside and out of our borders. When that happens, the abundance—the reign—of God will become real.

The poor are blessed. If the rich have more than enough, God makes up this imbalance through a special love for the poor. Tough as it may be for some to hear, the Lord’s biased in favor of the lowest among us; he takes their side. This isn’t because it’s good to be destitute, or because they’re better morally or religiously. As Jesus tells us in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, it’s simply because they’re suffering in a political-economy opposed to God’s will. Jesus identifies his very being with the poor, telling his followers that when they clothe the naked, feed the hungry, visit the prisoner—without asking questions—they do it to him. A Jesus country, then, takes the side of its poorest and most vulnerable members in all areas of social policy. It makes them its number one priority. And it realizes that in a world of stark inequality, God loves poor countries over rich.

III. Sacred Struggle, Righteous Resistance

Jesus doesn’t just talk the talk. He walks the walk. Unlike the fake populists of our day—grifters, demogagues, con-artists all—he’s the real deal, the genuine article. People know he’s authentic because he actually lives out his teachings. In addition, he gives his followers seven political strategems to animate their agitation:

Treat the People’s Needs as Holy. Throughout his campaign, Jesus treats the people and their needs as holy by healing them in mind, body, and soul. He asks his followers to commit to the same approach by teaching them an oath of allegiance: the “Our Father.” This isn’t a manual for personal prayer. Jews knew how to pray. Jesus is teaching them what to pray for, the goals and concerns of his movement. And its core meaning’s this: treat your neighbors and their needs as holy. Strive to fulfill their wants as if serving God. In sum, it’s a declaration to divest from the politics of Empire and invest in the politics of God—the scarcity economy for the abundant economy. Each part of the prayer spells this out:

“Our Father.” The prayer is collective, not individual. And it’s universal—it’s open to all who wish to make it. It acknowledges that God’s called the followers into the family of Jesus. They’re to fix their gaze not on personal wants, but the plight of others. It declares the community’s egalitarian ethos, to give generously, just as Jesus.

“Hallow your name.” To say God’s name’s hallowed, and not Caesar’s, was treasonous. Even more, it was to petition that the Lord demonstrate his holiness by bringing about social justice, as in days past. Jesus demonstrated this by following God’s will alone, and serving his people. He asks his chosen family to follow suit.

“Your kingdom come.” For God’s kingdom to come, Caesar’s must go. They cannot rule the same space. This is a call for revolution. Jesus made this declaration his personal motto. His followers are to struggle for the Kingdom at his side.

“Give us daily bread.” This is a demand to end Caesar’s reign, because Rome had reduced the people to starvation. To cry for bread is to cry for material security. Most revolutions begin with bread riots—when a regime can’t put food in people’s bellies, it loses legitimacy and is rapidly undone. Jesus and his allies demonstrate their legitimacy by feeding the crowds, meeting their material needs with abundance.

“Release us from our debts, as we release our debtors.” This is a pledge by Jesus’ followers to practice the Jubilee Year among themselves—to divest from the predatory credit system and cancel all financial arrears owed each other. And it’s a demand that the Jubilee be applied to the whole society, too—that the ruling class cancel debts and make reparations by restoring lands to their original occupants. Most revolutions, like in 1789 France, begin with peasants burning debt records. When the Jews finally rebel in 70 CE, their first act was to break into the Temple treasury and do the same. Anticipating their goal, Jesus tells the people their debts to God and their rulers were abolished.

“Rescue us from evil.” The community resolves to resist the temptation to give up the struggle and knuckle under Caesar and the collaborationist leaders in Jerusalem. Jesus embodies this by refusing to set himself up as a despot—to extract the resources of the land for himself, flaunt his power, become another leviathan.18 He came to serve the people’s needs, not his own.

Expose the Workings of Oppression. To bring people to action, a leader must first raise their consciousness. Jesus does this by educating the poor, ignorant peasants in the dynamics of injustice. In the parable of the workers, for example, he reveals how the robber barons of his day were exploiting laborers. The Greek word for “landowner” is oikodespotes, which means “plantation master” (or, literally, “despot”). The parable, then, isn’t about God’s generosity in some afterlife, but boss Scrooge in the corner suite: a petty tyrant who calls the workers lazy bums; hires them for the meager minimum wage (knowing their choice is accept or starve); and fires their spokesman for questioning his refusal to raise the earnings of those who worked longer.19

The parable ends with a declaration of class-reversal: in God’s kingdom, the last will be first and the first will be last. Or as the emancipated man, now a Union soldier, told a Confederate prisoner (and his former enslaver) at the end of the Civil War: “Hello, Master. Bottom rail on top this time.” By painting their plight in bold strokes, Jesus is telling the people—like the peasants I met in El Salvador—that their destitute state isn't God’s punishment for their sins. It's being caused by pernicious economic policies. And the solution isn't to pray for some miracle, but to stand in solidarity: there’s power in a union.

Call the Demon by Name. The story of how Jesus heals a man from Gerasa is often read as an account of demonic possession or mental illness. But upon closer inspection, it’s charged with political import. In The Wretched of the Earth, Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist Frantz Fanon recounts his experiences while treating imprisoned civilians during France’s war in Algeria. The prolonged torture they suffer induces mental breakdowns, which he diagnoses as “reactionary psychoses”—psycho-somatic responses to maltreatment that includes disruptions of menstrual cycles, hysterical lameness, and repeated masochistic episodes. The number of cases explodes as the conflict intensifies over the years. In the end, Fanon concludes that the prime cause of such epiphenomena is the brutality of colonial oppression.20

With his observations in mind, the story from Mark takes on new light: not a tale of individual deliverance, but of suffering by and healing of the body politic. The “man” in question is a symbol for the person of Israel. And his pathological behavior is being caused by the violence and misery of imperial rule. The “demon” also isn't singular, but collective: “We are many.” And they give themselves a curious alias: "legion," the name of the Roman army. This story's about how Jesus—filling the messianic role—defeats the evil of Empire, breaking the power of the cosmic tyrant. He sends its hosts not just “out of the country,” but into the sea—the symbol of primordial chaos, beyond God’s ordered creation.

Save Your Anger for the Mistreatment of Others. As a divinity professor once told my class, “Jesus is not a nice guy. He throws elbows.” He gets angry, though, about the mistreatment of others, not himself—he forgives even his own executioners. The story of his healing a leper exemplifies his righteous indignation on behalf of the weak. Jesus encounters someone who's been ostracized from his village because of a skin condition that may not even be Hansen’s disease (which was often confused with eczema and psoriasis).

On top of that, the passage of Leviticus that speaks of “clean” and “unclean” is meant to maintain public health, not relegate people to second-class status. But that’s what’s happened to this man. Most translations read that Jesus feels “compassion” or “pity” for him. But the Greek word found in a number of early manuscripts—orgistheis—means “moved with anger.” Likewise, embrimasomenos literally translates as “snorting with anger,” not, “sternly charging.” And eis martyrion autois really should read “testimony against them,” not “testimony to them.”

What’s going on here? Jesus becomes irate because the priests have obviously refused to pronounce this man clean and restore him to the community, as was their job. His anger rises against these theocratic leaders for their dereliction of duty. Taking authority upon himself, he pronounces the man clean and sends him to the priests as a sign of their broken regnancy. He doesn’t ignore the injustice he sees or just feel bad about it. He gets outraged and involved. He redresses it and rebukes the hierarchical system that quashes the lowly. In this, as in so much, he models the behavior he desires from his followers.

Take Blows Without Returning Them. Far from doormats, Jesus’ followers learn from him how to conduct a coordinated campaign of non-violent civil disobedience. This includes many tactics: Seize the moral high ground. Meet force with humor. Compel the powerful to confront decisions they haven’t prepared for. Deprive the oppressor of a chance to make a show of force. Be willing to suffer rather than retaliate. Such lessons and more come through many of Jesus’ instructions.

The command to “turn the other cheek,” for example, isn't just a generic personal ethic. It's about taking collective stands against higher-ups, who routinely dealt out back-handed slaps. Masters backhanded slaves, Romans backhanded Jews, husbands backhanded wives, parents backhanded children. The only thing victims could do was hang their heads in shame. To turn the other cheek instead, then, is to lean into the insult and thereby reclaim one's dignity. It's an act of defiance: “Strike me again if you like. I don’t care what you think of me. I'm made in the image of God.”

Likewise, the command about giving not just your coat, but your cloak as well, is really about predatory lending. Peasants, lacking land, were often forced to pledge their outer garments as collateral to pay taxes and debts (Exod 22:25-26). The scenario Jesus addresses, then, is the frequent one of a poor person being sued for debt default, being taken for everything but his underpants. To give that as well, then, means going beyond the ruling of the court—not in submissive acceptance of one’s plight, but in protest of coerced indigence. It symbolically says: “Take it all, even my undergarments. You've no power over me, because I give my possessions to you of my own free will.”

In these ways, Jesus teaches the people how to turn humiliating experiences into assertions of humanity, to throw their oppression back in the tyrant's face. By choosing to bear for an extra mile the loads that soldiers force upon them, they are engaging in acts of self-determination. They’re resisting their overlords without recourse to violence. He doesn’t instruct them to avoid conflict, quite the opposite. He trains them to seek it out and intensify it, in order to unveil the ugly core of injustice. Far from impractical, this kind of non-violent resistance works (over three times more than violence, according to Harvard scholar Erica Chenoweth). It aims for real, viable goals:

First, to convert one's opponents by appealing to their sense of decency.

Second, failing that, to make them accommodate changes to quell the unrest.

Finally, in the last resort, to force them to choose between reform or complete loss of power.21

Don’t Just Explain the Alternative—Show It. Jesus’ feeding of the multitude usually gets read as a symbol of the eucharist. But it’s not—it’s a politically charged symbolic act. As John’s gospel has it, the event occurs during Passover, when Jews were meant to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Yet instead, they throng to Jesus in Galilee. This is extraordinarily subversive on his part:

First, it relocates the center of theo-political power to him, not the Temple, completely undermining the priestly elites.

Secondly, to convene such a multitude—at least 5,000 men—usually means one thing: to form an army. Doing so without the permission of the colonial authorities constituted sedition. And sure enough, by the end of the day—after Jesus has filled their bellies to bursting—they’re ready to march on the capital and install him as king.

Finally, the people always had to give an offering at Passover, yet another financial burden. Jesus reverses this economic-religious exchange: he gives food to them, in a sign of the Lord’s abundance, as with the manna of old. He redefines their relationship with the divine; he establishes it not on offering pleasing sacrifices to Yahweh, but upon God’s largesse. In Jesus’ Kingdom, rulers are obligated to fill the people’s material needs. Like the profligate father in his parable, they’re to put away resentments, slaughter the fatted calf, and lavish society’s bounty on the poor. He turns a religious-economic system based on debt into one based on gift.22

Give Voice to the Voiceless. Jesus’ most revolutionary moment—the conduct that gets him arrested—is his direct action in the Temple. In a lightning strike, he leads a protest so disruptive that it halts all economic and religious activity. Without the collection of taxes, Temple sacrifices couldn’t be offered. And without that, the system loses its raison d'être. This is a public attack on the state’s central institution and its leaders, evoking the Maccabean precedent. After choosing to enter the city in overtly messianic fashion, Jesus now openly declares that he means to dismantle the Temple and set up his community as God’s dwelling place instead. The Temple complex was huge, the largest building in the known world. To shut it down implies that Jesus inspired a host of bystanders to join in. Such a visible assault was meant to snap the people out of the subservient awe inculcated in them by the ornate edifice and its mysterious priestly rites. It also demonstrated that the people had the right and power to challenge the authorities. It’s a key part of the radical playbook:

Confront the ruling class at the seat of their power to discredit them;

physically occupy the precincts to break the myth of invincibility;

maintain control of the site long enough to be seen as a viable challenger to the powers that be;

make dramatic gestures and pronouncements to seize people’s minds;

depart unscathed in an inspiring show of strength.23

With this brazen act, Jesus and his movement stand on the precipice of victory. Their agenda is poised to run the table. The revolution will be televised, live, today, from Jerusalem. And then, disaster: in an act of utter incomprehension, he surrenders to the authorities. He gives himself up without a fight, without even trying to escape. In the span of a few hours, he’s tried by the religious leaders, condemned by the mob, tortured by the procurator, and executed by the soldiers.

And not by just any instrument, but a cross—Rome’s ultimate symbol of degradation, a sign of divine curse under the Law of Moses. To be killed by the state in such an abject, public fashion could mean only one thing: Jesus’ campaign failed. Worse than that, he was wrong, wrong about it all: his claims, his practices, his identity. His way of political liberation—which had given hope to so many, galvanized them to offer all in their common effort—had met with ignominious defeat. Why on earth did he do it?

N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 205-209.

Edith Rasell, The Way of Abundance: Economic Justice in Scripture and Society (Minneapolis: Fortress Press), 61.

Wright, 160.

Wright, 151; 202-204.

Wright, 202-203.

Wright, 203.

Wright, 172-174; 235.

Wright, 272.

Wright, 251.

Wright, 262-263.

Wright, 258.

Wright, 323; 332; 340.

Wright, 430-431.

Wright, 276-277.

Wright, 296-297; 304.

Rasell, 61-94.

Rasell, 76-77.

Obery M. Hendricks, The Politics of Jesus: Rediscovering the True Revolutionary Nature of Jesus’ Teachings and How They Have Been Corrupted (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 101-108.

Hendricks, 132-139.

Hendricks, 53-54; 132-139.

Hendricks, 168-177.

Hendricks, 178-179.

Hendricks, 113-123.

Excellent write-up!