[This post is Part IV of a series. Here are links for Part I; II; III; V; VI; VII; and the Epilogue.]

I. Mapping the Nations

We now enter the most relevant section of our history of the American Nations: the recent past. How have the various 11 nations behaved politically since 2008? We’ve got a lot to cover, so buckle up! To start, I want to share three maps. These show the results of the presidential elections from 2008-2016 by state, which are shaded according to the popular vote margin-of-victory:

2008 Presidential Election

2012 Presidential Election:

2016 Presidential Election:

You see a clear trend, can’t you? In 2008, Barack Obama racked up commanding leads in New England, New York, and Minnesota-Wisconsin-Michigan—the heart of Yankeedom. He also won Iowa, Pennsylvania, and Illinois solidly, along with close victories in Indiana and Ohio—all states that contain the Midlands. He took Virginia by a healthy margin, and even North Carolina—Tidewater. In the El Norte region of Colorado and New Mexico, he romped. In sum, he owned the three classic Left-bloc nations—Yankeedom, Left Coast, and New Netherland—and convincingly conquered the swing regions of El Norte, Tidewater, and the Midlands.

In 2012, something started to change. North Carolina and Ohio flipped to the Red Southern coalition. Virginia turned grey, and Colorado and New Mexico got lighter in color. But what’s most striking is that trifecta of Minnesota-Wisconsin-Michigan: they turned a brighter hue of blue, as did Pennsylvania. Still in Obama’s column, but less solidly.

The transformation was complete by 2016. Indiana went deep red, Ohio and Iowa not far behind. Pennsylvania rusted, as did North Carolina. Colorado got grey, with New Mexico even lighter blue. And the shocker: Wisconsin and Michigan turned red. Even Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Maine are grey—meaning Hillary Clinton’s margin-of-victory was under 5% there. In fact, Connecticut—Connecticut!—turned lighter in color, along with Delaware and New Jersey. What the hell happened?

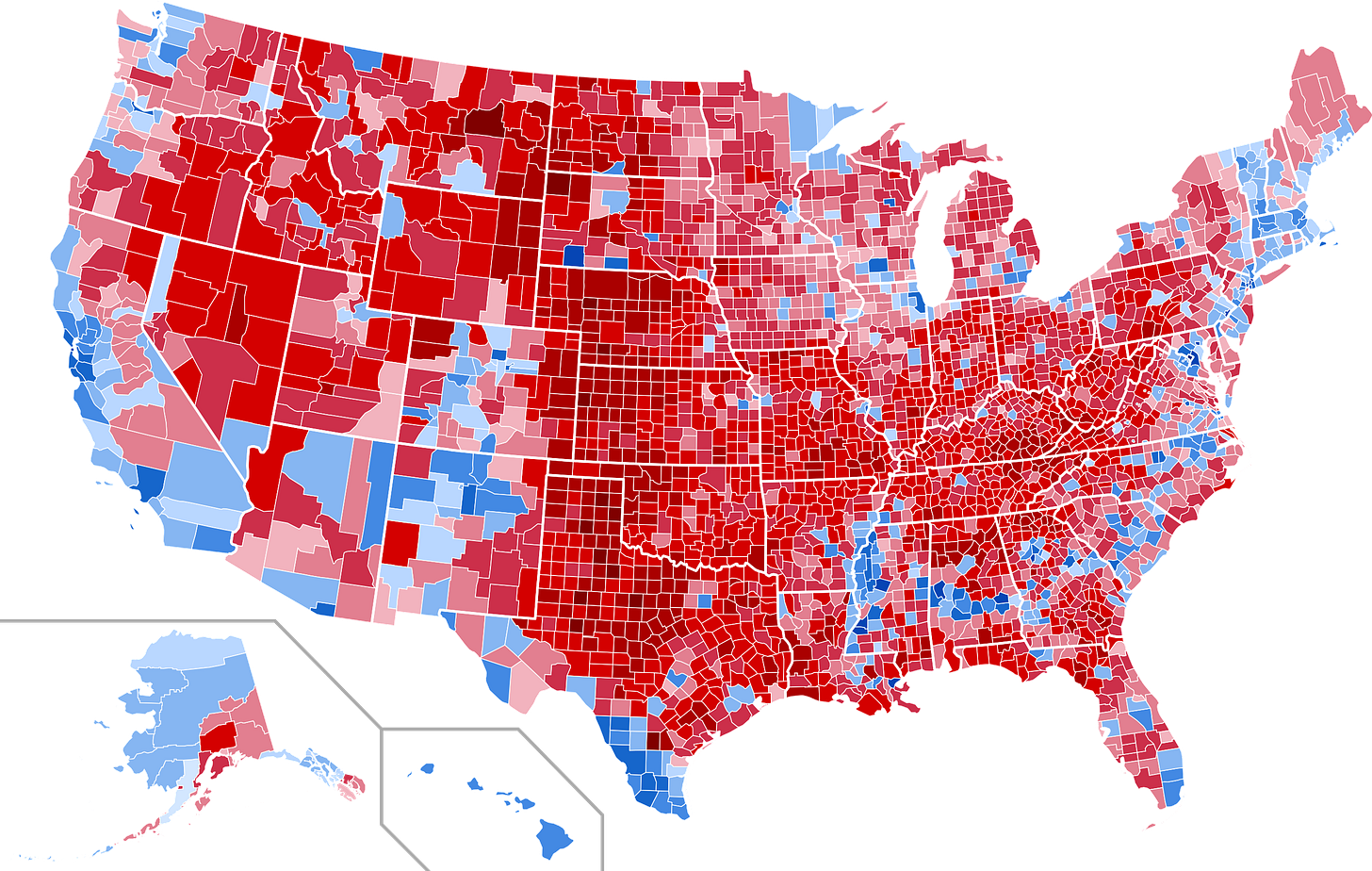

To begin to get an answer, let’s look at three other maps (all from Wikipedia). These show the results of those same elections on the county level, again shaded (by margin-of-victory) blue for Democrat and red for Republican :

2008 Presidential election results by county:

2012 Presidential election results by county:

2016 Presidential election results by county:

As you compare them, what do you discern? In 2008, scores of counties in Wisconsin, Iowa, the eastern half of the Dakotas, Minnesota, northern and western Illinois, eastern Missouri, and Michigan went blue. This unique area is known by the felicitous moniker of the “Upper Mississippi River Valley Anomaly,” or the UMRVA—where Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Missouri, and Illinois all converge. Obama also won a string of counties in northern Ohio along the rim of Lake Erie, and large swaths of upstate New York. And in New England, every single county save one (in backwoods Maine) was in his column.

Just four years later, blots of red have bled into these regions. The blue enclave in the UMRVA has shrunk, with a red gash across rural Wisconsin, and Michigan almost entirely turned red. Several counties in Iowa and Illinois have reddened as well, as have three in rural New Hampshire and even one in western Connecticut.

By 2016, the takeover is total: a sea of red dominates the UMRVA and Michigan. That Lake Erie blue string in Ohio and Pennsylvania? Gone. Upstate New York? Awash in red. And most staggering of all, many counties in New England have flipped to the Republican column—including most of Maine and six out of ten New Hampshire counties.

The biggest movement occurred in that UMRVA region; Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio; and rural Pennsylvania-New York-New England—the Heartland, the Great Lakes, and the Northeast. It’s this shift that accounts for Donald Trump’s electoral college victory in November 2016—a trend that pushed Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania fully into his ledger. All other regions of the country remain constant across the cycles. When you graph these trends onto the American Nations map, you can see clearly where these flipped counties lie—in the Midlands and Yankeedom. This change bears out in the margins-of-victory from the three cycles, stratified by ethno-nation:

The numbers, compiled by Colin Woodard, validate the maps. Every region stayed consistent across the elections except two—the Midlands and Yankeedom. The former voted for Obama by 11 points in 2008. In 2012, only by 6. And in 2016, it went for Hillary Clinton by just 0.4 precent—a virtual tie. A similar disaster struck Yankeedom. Obama won the region in 2008 by a commanding 19 points. In 2012, he was down to 16, still very strong. But in 2016, Clinton captured the nation by only 8—a collapse of half from the previous cycle, and an 11-point drop from 2008.

This change from Democrat to Republican in the upper North is shocking. After all, this is Yankeedom we’re talking about—the dominant ethno-nation of the Left bloc. Historically (as Woodard relates) the rural counties of Yankeedom have voted in sync with the cities in its region. What has happened to cause so many of them—as well as their neighbors in the Midlands—to defect to the Deep South and Greater Appalachia? Answering that is the key to understanding the state of the Union today. To do that, we have to back up and tell the whole story.

II. 2008: Obama’s Midlands Mandate

If history repeats itself in bad ways, it can repeat itself in good ways, too. The 2008 financial crash was a replay of the Great Depression. In response to the crisis of the ‘30s, Americans chose the social democratic solution of Yankeedom. So, why not try it again? But the Blue coalition’s alliance with the Deep South was long dead. America had swung right-ward. In this reversion to its regional alignment, the Deep South and Appalachia were not inclined to opt for another New Deal.

Moreover, though the free-market capitalism of New Netherland and social conservatism of Tidewater had once again been discredited, the Democratic Party clung to neoliberal orthodoxies. To wit, its presumptive nominee was Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton, who promised to go back to the Third Way policies of her husband that had wreaked havoc on working people in rural Yankeedom and the Midlands.

The disastrous Iraq War, however, gave an opening for a challenger to her left. Barack Obama’s insurgent candidacy was fueled by his anti-war position. Combined with his charisma, youth, and intelligence, he evoked Bobby Kennedy in his doomed 1968 campaign. Obama was an enigma; he even described himself as a Rorschach test. Everyone found in him something to identify with. A native of Hawaii, he imbibed its relaxed Aloha Polynesian spirit. He studied at universities in New Netherland and Yankeedom, and made his home in Chicago—founded by Yankees but, as Woodard calls it, really a border city that opens to the Midlands.

The contradictions in his identity—which he examined lyrically in his first book, Dreams from My Father—bore out in his campaign. On the one hand, it played up themes of sweeping transformation: Hope. Change. Yes, we can! His rhetoric, backed by a cinematic soundtrack, stoked messianic expectations—especially in Millennials. No national leader had spoken this eloquently in their lives. But deep down, Obama wasn’t FDR, or even a Kennedy liberal. In a sign of the success of the Reagan Revolution, the young Senator considered himself temperamentally conservative.

In truth, his politics—as he told the DNC in 2004—were neither Right nor Left. Rather, they were communitarian. He tapped into the tradition of civil religion as expressed by Robert Bellah and, more recently, Yale’s Philip Gorski in his 2017 book American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Civil religion is “the founding myth of a political community, through which it interprets its historical experience in the light of transcendent reality,” says Gorski. He further identifies America’s civil religion as “prophetic republicanism,” a blend of the prophetic theology of the Hebrew Bible and the political tradition of republicanism (the philosophy the American Founders actually ascribed to—not liberalism).

Prophetic republicanism draws on the Exodus narrative, with its movement from slavery to freedom. In this vision, as Gorski says, America is:

…a diverse people marching together through time toward a Promised Land across landscapes both light and dark. It is hopeful without being fantastical, and progressive without being naively optimistic. It uses the cement of the common good to bind the prophetic voice of the jeremiad with the traditional themes of civic republicanism. We will never get there, but it is all in the trying.

I’ll unpack prophetic republicanism in a separate post, as I think the Left today must master it in order to win nationally. For now, we can sum up its vision thus:

The dream of the prophetic republican tradition is of a righteous republic: a free people governing themselves for the common good. A righteous republic is based on a certain vision of the common good—not just any vision, but one that draws deeply from prophetic religion. The prophetic ethic is social as well as individual.

Obama mined this tradition with gusto—the first presidential contender to do so since Mario Cuomo’s remarks to the DNC in 1984. But he used that rhetorical register to call not so much for big government as for civic renewal. This spirit of democratic togetherness was captured by powerful speeches such as his “More Perfect Union” address on race. He began his career as a community organizer, after all, and believed in the art of compromise and his ability to reason with people of goodwill. Though his campaign was animated by a heady infatuation, on paper he offered temperate cultural change and small-bore policies.

This is a politics of neighborliness that columnist David Brooks extols in his “Agenda For Moderates,” where he argues for a politics based on four affections: love of our children, of our work, of our place, and of our shared humanity. “Moderation is not an ideology,” he says. “It is a way of being. It stands for humility of the head and ardor in the heart. When you listen to your neighbor, you see how many perspectives there are and you’re intellectually humble in the face of that pluralism. When you listen to your neighbor, you see that deep down we’re the same and you hunger to deepen that connection.” Elsewhere, Brooks enumerates eight key moderate ideas:

The truth is plural.

Politics is a limited activity.

Creativity is syncretistic.

In politics, the lows are lower than the highs are high.

Truth before justice.

Beware the danger of a single identity.

Partisanship is necessary but blinding.

Humility is the fundamental virtue.

When you examine this taxonomy, you see that it’s a sound distillation of Obama’s politics at their best (which is probably why Brooks supported him). It also perfectly describes the key swing region in the American Nations: the Midlands. Here’s Woodard’s description from his book:

The Midlands is the most philosophically autonomous region of the nations, for centuries leery of both meddlesome, messianic Yankees and authoritarian Dixie zealots. Midlanders share the Yankees’ identification with middle-class society, the Borderlanders’ distrust of government intrusion, the New Netherlanders’ commitment to cultural pluralism, and the Deep South’s aversion to strident activism. It’s truly a middle-of-the-road American society and, as such, has rarely sided unambiguously with one coalition, candidate, or movement. When it has—for FDR in the 1930s, Reagan in the 1980s, or Obama in 2008—it has been at a time of profound national stress and in reaction to perceived excess. It’s no accident that the Midlands straddle—but do not control—many of the key “battleground states” at the turn of the millennium: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri.

Though it was founded in Philadelphia, the center of the Midlands today happens to be the very state that serves as the launchpad for presidential campaigns: Iowa. As Woodard argues in Politico, despite its small size and obscure location, Iowa is the right place to anoint contenders for the White House. Its kitchen-table politics makes the perfect bellwether for the nation’s mood, as it forces candidates to move to the center:

What brings Iowans together is a fundamentally Midland ethic of pluralism, equality and fairness, one reinforced by living in what was long a landscape of family-owned farms and small-town producers, an economy that nearly realized the Jeffersonian vision of economic and civic equality.

Such an ethos dovetailed with Obama’s views. He lived next door in Illinois, after all, and interacted with Midlanders in the state frequently while serving in the capital of Springfield. He’s spoken of the comfort and familiarity he felt when he met Iowans in their kitchens, diners, and porches. They reminded him of his grandparents, who raised him and hailed from the Midlands sections of Kansas themselves. Despite racial differences, the culture of Iowa was his culture.

So, it’s no surprise, in the end, that Iowans chose Obama in the 2008 caucuses, catapulting his candidacy to national prominence. I recall the electric feeling in the air the night of his victory, punctuated by a speech that showcased the love the Midlanders had for him. “That man will be President,” my father said as we watched. He was right. Soon, the euphoria swept the nation.

With the conservatives utterly discredited by George W. Bush’s disasters, Obama road this broad wave to power. On election night, he won 69,498,516 votes to John McCain’s 59,948,323, capturing the Midland states of Iowa, Illinois, and Ohio. On the congressional level, Democrats took the popular vote by 10.2%, picking up 21 additional House seats for a 257-178 majority. They had a near 60-vote majority in the Senate, and controlled many House districts in the Deep South, El Norte, Greater Appalachia, Tidewater, the Midlands, and rural Yankeedom:

III. 2010-2015: Things Fall Apart

Yet within this coalition, fissures existed. Yankeedom and the Left Coast expected a return to the New Deal after decades of “trickle down” economics, as well as big wins on social issues. But the Midlands, as mentioned, preferred moderation. The bankers of New Netherland, for their part, were nervous that the young President would indeed go full-FDR on them. Once in office, though, his cautionary instincts and inner neoliberal drove him back into their arms: he appointed a former Goldman Sachs executive as his Treasury secretary, and named Larry Summers—a Third-Way Clintonian—as his chief economic adviser. Meanwhile, down South, the sight of a Black President activated the region’s ancient racial resentments.

In other words, the core regional divides that have always polarized the American federation thwarted Obama from the outset. The economic situation called for government intervention on the scale of the New Deal. But unlike the ‘30s, there wasn’t the will, even in the President. His response wasn’t as blinkered as the austerity measures of Germany. Yet his stimulus was way too small, in hindsight, and he bailed out bankers without overhauling an economy that many rightly saw as rigged in favor of the rich. As he put it in his recent memoir, Obama didn’t want to do “violence” to the system. But major surgery is violent. And capitalism needed major surgery—if not an outright socialist transplant.

With hopes so high, the man could never have satisfied everyone. But through his halting response to the crash and reliance on Beltway insiders, he lost the favor of everyday folks. After all, they’d wanted an outsider who would break up the oligarchy. Soon, twin populist uprisings began: the right-wing Tea Party and the left-wing Occupy Wall Street. These dual movements (flip sides of the same coin, really) presaged the 2016 campaign what with their feelings of betrayal by and resentment of elites: a ruling class that Obama now epitomized.

Then, the President shifted to healthcare, and lost the plot. The debate over the Affordable Care Act was baffling. On the one hand, the law he signed was a market-based work-around for a fundamentally broken system. A neoliberal “public-private” partnership, it had the Federal government regulate exchanges for poorer Americans to purchase insurance. This approach satisfied the Midlands’ desire for prudent government intervention to help out everyday folks, while avoiding top-heavy state power.

Yet, for everyone else, it was a disappointment. The Left was incredulous that, even with such huge congressional majorities, their favored single-payer plan was nixed. Even a public option was scratched thanks to the last-minute machinations of Sen. Joe Lieberman, a conservative Democrat who’d stumped for McCain. On the Right, the plan was dubbed “Obamacare” and likened to Stalinism, complete with government death panels prepared to euthanize elders.

Meanwhile, by not getting a New New Deal, the economy struggled to recover. On top of this, Obama’s characterization of the arrest of Prof. Henry Louis Gates by Cambridge police as “stupid” further inflamed latent racial animosities. His poll number took a dive. And on the foreign policy front, instead of bringing America’s Forever Wars to a close, he surged troops into Afghanistan (in an echo of Nixon’s Vietnam strategy) and escalated the drone war.

Put together, the result in the 2010 midterms was a catastrophe for Democrats. The Republicans swept back into control on the basis of low turnout and an enthused base, picking up 63 seats and winning the popular vote 51.7% to 44.9%. For the Democrats, it was the greatest loss by a party in a midterm since 1938, as well as the largest House swing since 1948. The GOP picked up seats in El Norte and the Midlands, ran rampant through much of the Deep South and Appalachia, and even made gains in rural Yankeedom:

On the state level, the result was even worse: the Democrats went from controlling 27 legislatures to 16. This massive setback scuttled all hopes for grand progressive legislation. Obama was able to pivot enough to win re-election in 2012, especially after Republicans overplayed their hand with stupid stunts like defaulting on the national debt. But support for him was beginning to erode within the Blue bloc. Still, even by 2016, his brand of civil discourse, good-faith attempts at compromise, and incremental progress fit the overall mood of the country. On the eve of the 2016 election, his approval stood at 53% to 45% in his favor. Had Barack Obama been eligible for a third term that fall, he probably would’ve won.

IV. 2016: The Great Yankee Defection

But he wasn’t. Instead, Democratic Party elders anointed Clinton once more. The result stunned the nation. Donald J. Trump, a mendacious real estate mogul from New Netherland, bested her in the North. As we can see on the above map, huge swaths of the UMRVA reddened. Same for Michigan, Ohio, New York, New Hampshire, and Maine. The Blue bloc was fractured.

The thesis of Woodard’s book is that ethno-nations change very slowly from their cultural foundation. Thus, for rural Yankeedom to defect from its regional identity in 2016 and ally with the Southern bloc is a seismic event in U.S. political history—an almost unprecedented situation. In the past, Yankeedom has tried to remake other nations—specifically the Deep South, its ancient foe. But in 2016, Dixie accomplished in Yankeedom what the latter had always failed to do: win hearts and minds. Woodard sums it up as follows:

These “Trump Democrats” were almost entirely a phenomenon of Yankeedom and the Midlands, communitarian nations where the traditional Republican message—that fewer taxes, regulations, and public investments will result in more freedom—have never found purchase. Trump’s campaign message resonated here, especially in more homogenous white rural counties.

How did this happen? Why did these sections of the Midlands and Yankeedom defect to the South? Katherine Cramer, director of the University of Wisconsin, has spent years in the UMRVA interviewing its people and studying its attitudes. What she found is striking. These areas aren’t deeply conservative, as noted before—they’re communitarian or even liberal. And it wasn’t economic desperation that drove its voters to Trump. Nor even racism (though that played a complex, partial role). Rather, it was a sense of grievance against urban Yankees and Midlanders, as she relates:

Most significantly, the people I talked with thought that they were not getting their fair share of respect. They perceived that in the rare cases that people in the cities paid any attention to people in places like theirs, they ridiculed rural folks as uneducated racists…I conducted a survey in 2011 that found that 70 percent of rural residents believed the government “ignored” their community, compared with 52 percent of urban respondents and 47 percent of suburban respondents.

Here’s where the urban-rural divide really does come into play. Left behind by city slickers, voters in rural Yankeedom and the Midlands desire a government that pays attention to them—the way the Democrats did during the New Deal. As Cramer told Jacobin in 2020, it turns out they do want the second coming of FDR after all. This is borne out by the results of the 2016 Democratic Presidential Primary, via this map:

2016 Democratic Primary results by county

As you can see, Bernie Sanders destroyed Clinton in rural Yankeedom and the Far West. And he went toe-to-toe with her in the Midlands (Iowa, Missouri, Oklahoma, eastern Dakotas) and El Norte. He won every single county in Wisconsin—the very same places that went for Trump in the general. He won central Pennsylvania; all of Kansas; almost all of upstate New York; and nearly every county in New England. Incredibly, he won every county in West Virginia, almost every county in Indiana, and half of Kentucky—bastions of right-libertarian Appalachia. (Clinton’s support was, paradoxically, in the Deep South and Yankee cities—the former because it hates socialism and the latter because their residents are wealthy liberals who emphasize identity politics over economic redistribution.)

How does this make sense? It’s actually pretty intuitive, as Woodard explains:

Though [Hillary Clinton] ran as a successor to Obama, both Bernie Sanders and Trump were able to tie her to her husband’s neoliberalism, a policy legacy that included welfare reform, deregulation of the financial industry, passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the famous pronouncement that the “era of big government” is over, which some of his top aides interpreted as a repudiation of the very New Deal politics that once gave the party a lock on blue-collar workers.

Recall that Yankeedom actually favors big government and central planning—not laissez-faire capitalism. And the Midlands is fed up with a trickle-down economics that benefits coastal elites who don’t care about small-town America. This opens the door for more communitarian political ideologies—like nationalism and socialism.

Despite being polar opposites on everything else, both Trump and Sanders shared a belief (at least during the campaign) that neoliberalism was a failure. They each promised to use the government to restructure the economy for the benefit of everyday folks. Sanders ran as a European-style social democrat, the most full-throated campaign for social democracy since 1932. His rallying cry of the 99% against the 1% and denunciation of corporate greed resonated with backcountry Yankees who feel left behind.

On the flip side, Trump’s vision was unabashedly nationalist, as Woodard describes:

Recall that Trump, alone among the 17 candidates for the Republican nomination, did not run on a laissez-faire agenda, but rather as a European-style ethno-nationalist, promising robust government intervention and social programs for a subset of Americans and extralegal or extra-constitutional punishment for others…He advocated for government-led protectionism, industrial intervention, infrastructure spending, and the replacement of the Affordable Care Act with “something terrific.” Social Security and Medicaid would be protected, the swamp of Washington would be drained of its lobbyists, and more taxes might be levied on the rich. It was, in libertarian versus collectivism terms, the most communitarian-sounding set of campaign promises from any Republican nominee since Richard Nixon.

When primary day dawned, rural voters in Yankeedom and the Midlands made their preference clear: either nationalism or socialism. No more neoliberalism. Despite its best efforts, the Republican establishment split its votes among several candidates, resulting in victory by the nationalist Trump. Corporate Democrats, on the other hand, worked their process so as to deny the socialist Sanders their nomination. Come November, rural Midlanders and Yankees saw only one of their two populist, anti-elite champions on the ballot—Trump.

To the shock of urban liberals, the uncouth, pathologically-lying Manhattanite connected with these voters. He did so on the level of emotion, narrative, and values. A demonic parody of Obama, the con-man tapped into their feelings of abandonment, their desire for an outsider to return the government to everyday people, and added a dose of white identity politics to boot. He traded on their suspicion that too much help goes to “undeserving others,” i.e., urban white-color professionals, minorities, and undocumented immigrants.

Despite the fact that they’re doing rather well economically, the perception of these Americans is that they’ve been forgotten—and in politics, perception is reality. “They were doing what they perceived good Americans ought to do to have the good life, and the good life seemed to be passing them by,” Cramer says. “Part of Trump’s appeal was that he gave people a story, however false or partial, about whom the good life is going to.”

In other words, as Woodard relates, within the noise of Trump’s candidacy, a clear signal emerged…

…especially in rural parts of Yankeedom and the Midlands, where most people belong to Trump’s “in” group of white, native-born Christians and don’t have many friends and neighbors on his list of undesirables: Mexican-Americans; Muslims; immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador, or sub-Saharan Africa; and professional journalists. While Clinton’s margin in Urban Yankee counties slipped by 3.6 points and in Midland urban counties by 3.2, compared with 2012, Trump increased his party’s margin of victory by 18.3 points in both rural Yankeedom and the rural Midlands, winning the latter category by more than 40 points.

Counter-factual history is impossible to prove, but had Sanders opposed him, the Vermont Senator likely would’ve prevailed. Many rural Midlanders and Yankees did not, in fact, like Trump the man. Sanders’s egalitarian economics, cultural moderation, and bone-deep authenticity would’ve cross-pressured these voters, pulling just enough of them left to blunt Trump in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and perhaps Wisconsin (where Clinton lost by only a few thousand votes). But as it was, they didn’t have to face this dilemma; they easily picked the communitarian Trump over the individualistic Clinton. History will judge the Democrats harshly for failing to nominate a social democrat to face a fascist.

V. 2020: Buyer’s Remorse

So, how did this bet on Trump turn out? Suffice it to say, not as expected. Instead of getting the government help they desired, rural Yankeedom and the Midlands saw the 45th President implement oligarch-friendly policies—from the 2017 give-to-the-rich tax bill to the GOP’s failed attempt to destroy the Affordable Care Act with (surprise) nothing “terrific” to replace it. On top of that, Trump brought a climate of chaos into office, leading to one constitutional crisis after another. Exhausted, the voters in the Midlands and Yankeedom soured on him quickly. This buyer’s remorse played out in the 2018 midterms in the above map, with the Democrats picking up key House seats in Yankeedom, El Norte, and the Midlands—including three in that strange UMRVA.

As the insanity of Trump’s White House continued—replete with an impeachment and his erratic handling of the pandemic—these regions turned on him further. The 2020 Democratic Primary was another roller-coaster. Sanders emerged as the front-runner after wins in the Iowa Midlands, Yankee New Hampshire, and Hispanic Nevada. As you can see in the map below, he won a cluster of counties in Iowa, North Dakota, and Minnesota, as well as rural Yankee ones in Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont. He swept the counties of the Far West regions of California, Nevada, and Utah. He also won almost every county in Colorado, and a string of ones in south Texas along the Rio Grande—the heart of El Norte.

But—following the command of Congressman Jim Clyburn, who’s taken more money from Big Pharma than any other member of Congress—Deep Southern voters went with the more conservative Joe Biden in South Carolina. This right-wing region was always bound to pick him over the socialist Sanders. But the media spun a comeback narrative that revived the Delaware don from his political death bed. At that, party big wigs—led by Obama—conspired yet again to rally ‘round the establishment and block Sanders. (His campaign didn’t really compete after that, hence the blue Biden counties in the rest of the country.) You’d think the Democrats would’ve learned their lesson from 2016 and gone with the populist champion of rural Yankeedom, the Far West, and El Norte—indeed, the most popular active politician in America. But no.

Biden hails from Wilmington, Delaware, which juts into the Midlands. His promise to return politics to normal—without fundamentally reforming the economy—reassured his friends in that section (along with capitalists). So did his working-class Scranton roots and record as Obama’s VP. Contrasted with the hurricane of Trump, it was enough—just enough—to entice rural Yankees and Midlanders back to the Northern bloc. Woodard ran the Election Day numbers by nation and produced the results:

2020 Presidential Election results by nation

Greater Appalachia: 59.5-39 for Trump (+21)

New France: 59.5-39.4 for Trump (+20)

Deep South: 53-45.6 for Trump (+7)

Far West: 51.3-46.6 for Trump (+5)

Midlands: 50.1-48.3 for Biden (+1.8)

Spanish Caribbean: 52.7-46.6 for Biden (+6)

Yankeedom: 54.3-44.2 for Biden (+10)

Tidewater: 58.7-39.8 for Biden (+19)

El Norte: 59.9-38.6 for Biden (+21)

New Netherland: 60.8-38.4 for Biden (+22)

Left Coast: 67.7-30.3 for Biden (+38)

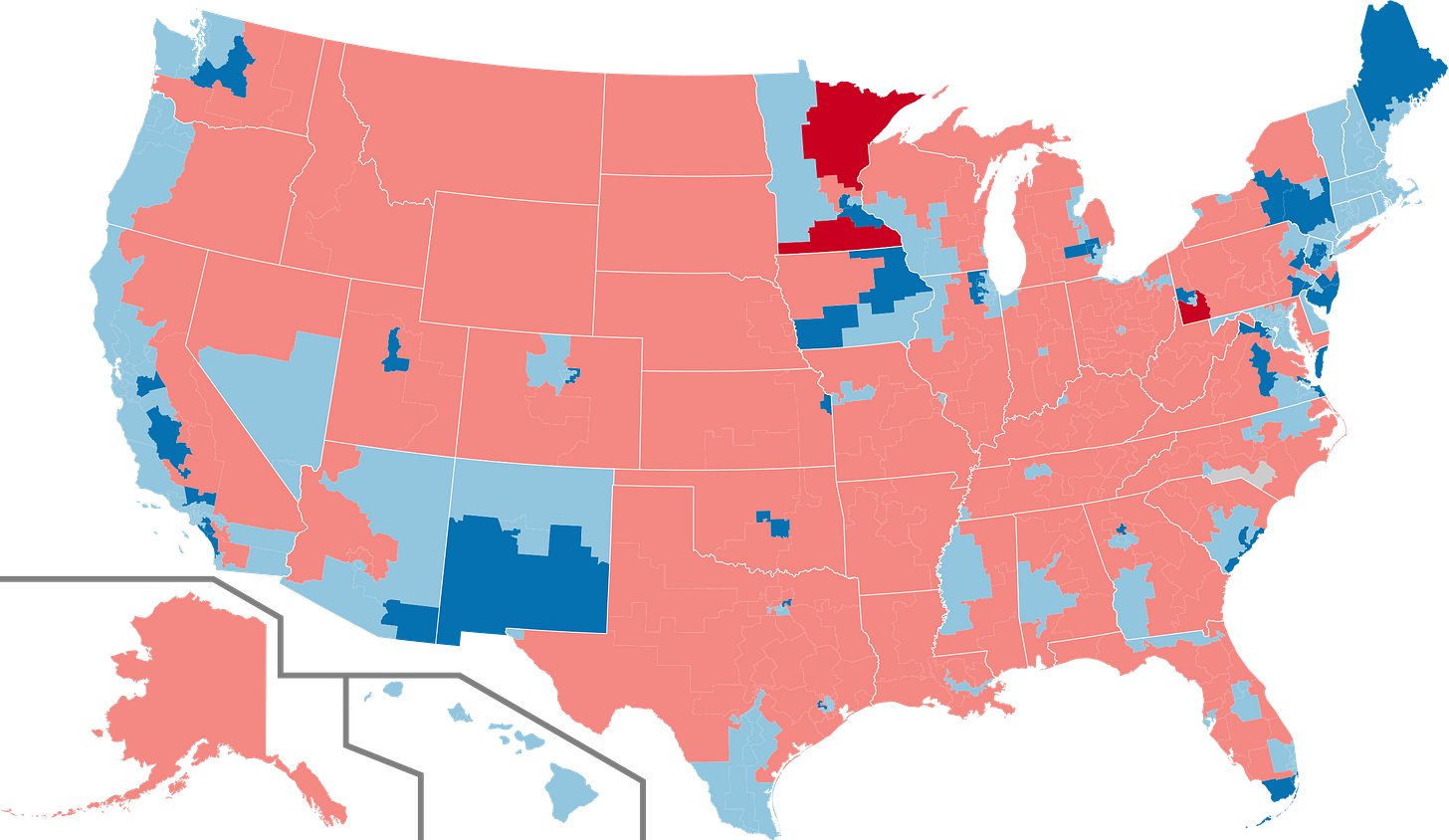

Turned into a map, the regions in 2020 looked like this:

Compare it with the same map from 2016:

You can see the reverse-shift. Disturbingly, Greater Appalachia, the Far West, and the Deep South increased their support for the fascistic Trump. Like arteries clogged by plaque, America’s red regions hardened. The Midlands, on the other hand, got bluer—barely. Biden took the region by 1.8 points, compared to the 0.4 margin of Clinton. As Woodard says, that’s better, but still a problem for the Democrats:

Obama won the Midlands by 11 points in 2008 and 6 in 2008. Biden’s margin was not sufficient to put Iowa or Ohio into play, but it did give the critical boost in Pennsylvania, allowing him to compensate for that state’s substantial, ruby red, Appalachian section.

Yankeedom also became bluer, as Biden won the region by 10 points, up two from Clinton’s 8. Woodard summarizes as follows:

In “Greater New England,” Trump’s standing in both urban and rural counties declined—by 6.3 and 8 respectively. But he still won rural Yankeedom (which went for Obama by 5.9 percent in 2008) by 10 points, 58 to 48. Rural Yankeedom softened on Trump but remained in his camp.

But the county level, things still look grim for the Democrats:

2020 Presidential Election results by county

Again, if you compare this map to the 2016 version, you see the problem. Biden didn’t actually flip many counties blue. That pesky UMRVA region of the Midlands remained red, as did Michigan, Ohio, and rural Pennsylvania. If anything, they look more red. What this probably tells us is that the Democrats ran up their numbers in the cities and suburbs within the Midlands and Yankeedom and offset the rural vote in the same regions. The underlying issue, then, remains: the Midlands—the key swing region of the federation—has soured on the Blue bloc, along with backcountry Yankees.

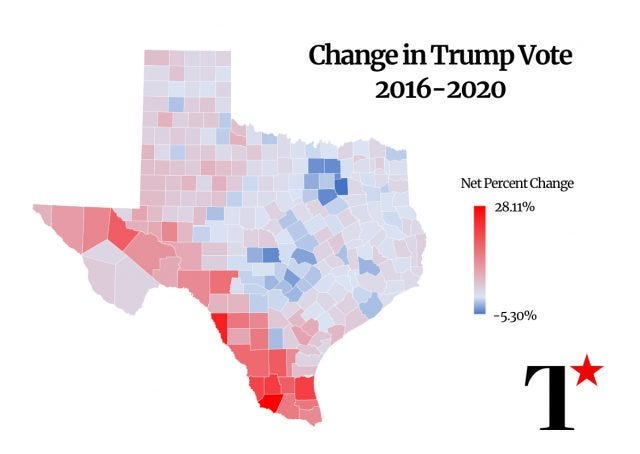

If that isn’t enough, a new headache emerged: El Norte. The other great swing region, it’s a centre-right culture that emphasizes faith, family, entrepreneurship, and tradition—a natural fit for the GOP. But because of the Republican Party’s hostility to immigrants, especially under Trump, it’s gone solidly for the Democrats over the past fifteen years. Clinton won it by 19 points in 2016, and Biden expanded that lead to more than 21 in 2020.

So what’s the matter? Woodard explains:

Embedded in Biden’s El Norte victory is a shocker: a staggering flip to Trump in rural El Norte, where people of Hispanic descent are the overwhelming majority. Clinton won these counties by nearly 40 points in 2016, and Obama won them by 42 in 2008. On Nov. 3, 2020, Trump won them by just over 10—a mammoth 48.7-point swing. In the most rural subset of the region’s counties—those that don’t have a single town (or cluster of towns) with 10,000 people—Trump’s margin was 18.5, an unheard of 75.6-point swing in his favor compared to 2016.

The damage was concentrated in South Texas, including the Rio Grande Valley, where Spanish is the mother language of a supermajority of the population, and has been since Europeans first colonized it more than three centuries ago. One rural county—Zapata—flipped red for the first time in a century, and Biden’s margins of victory were blunted from El Paso to Brownsville. Were it not for this newly emerging trend, Democrats could feel confident of flipping Texas in four years, effectively banishing their rivals from the White House. Exploring what happened there should be both parties’ top priority.

We’ll explore what’s happening in rural El Norte more in my next post, and what the Left’s strategy must be going forward. Remember, though, that Sanders swept those same counties in the Democratic primary. Overall, then, the picture from 2008 to 2020 couldn’t be clearer. To win the United States, the Left must:

Learn the cultural values of the Midlands, Yankeedom, and El Norte and connect them to leftist ideas.

Make residents in the rural counties of those regions feel heard and respected.

Deliver a Sanders-style message of cultural moderation and economic populism through stories that will resonate emotionally.

If the Left can do these three things, it might have a fighting chance. If not, it will be reduced to a rear-guard defense of its beleaguered, isolated cities. En avant!