[This post is Part VII of a series. Here are links for Part I; II; III; IV; V; VI; and the Epilogue.]

We’ve reached the penultimate post in my American Nations series. (Previous installments here: One; Two; Three; Four; Five; Six.) It’s a longer one, but I did give you a week off. I want to finish laying out my five-point plan for how the Left can compete in national elections. To recap, the first three are: 1) Learn the cultural values of the Midlands, Yankeedom, and El Norte and connect them to leftist ideas. 2) Make residents in the rural counties of those regions feel heard and respected. 3) Deliver a Sanders-style message of cultural moderation and economic populism through stories that will resonate emotionally. Here are the final two:

Play smart identity politics.

Master the rhetoric of prophetic republicanism.

I. Identity Politics

The classic Left, from the late 19th century through the ‘70s, focused on labor and workers’ empowerment. It rooted itself in unions, prioritized economic equality, and championed public goods and services: pensions, healthcare, transportation, schools, housing, etc. Starting in the ‘80s, however, it became detached from labor and started taking its talking points from discourses emanating out of critical studies departments in the university. This academic lounge conversation dwelled on cultural issues and special interests. Instead of trumpeting universal rights and benefits, it narrowed its lens to boutique concerns and particular communities. It replaced language about the common good with an emphasis on marginal groups and ever-edgy niche identities. Rather than preach solidarity among the working classes, it hammered a message of diversity, difference, and absolute individualism.

As a result, today’s Left is fractured. Bernie Sanders revived the old tradition of labor and social democracy; American socialists prioritize the community over the individual when it comes to economics. But, as David Brooks pointed out recently, in the cultural sphere—in the private domain—it holds the opposite: autonomy takes precedence over traditional moral systems that would impinge on personal agency. (The Right, for its part, is the mirror opposite: it preaches a conformist message in the private domain, but unhinged self-interest in the economic.) As I said last time, to win the hearts and minds of Americans, the Left needs to return to its classic message of economic fairness and universal goods. When it comes to culture, on the other hand, it should tread lightly. Sanders’s 99% talk resonates with average Americans. The identity discourse, however, is a big turn off.

Don’t believe me? Look at what’s just happened in Chile. In 2019, students led a massive street uprising in response to decades of austerity and neoliberal inequality. The core issues animating the protests were economic and social: lack of affordable healthcare, poor public transit, a broken welfare system, over half of elderly people without pensions. As a result, the Left surged to power and won a national referendum to write a new constitution, with over 80% in favor. When elections were held to send delegates to the constitutional convention, the Right refused to field candidates. The result was an assembly made up exclusively of radicals. The most conservative representatives were socialists. To their left were delegates from new parties that emphasized the kind of perspectival politics mentioned earlier—especially gender identity and indigenous communities.

With complete control of the chamber, they should’ve recognized a trap. Instead, they hoisted themselves on their own petard. The identitarians dominated the debate, which featured moralistic harangues, militant discourse, and transgressive stunts—like when a woman delivered an entire speech bare chested. Rather than offer economic relief and material uplift, the charter leaned heavily into culture. Gender “perspective,” for example, received fifty mentions in the new constitution. Indigenous rights and ideas of “pluri-nationality” got seventy-five. Social security, on the other hand, was mentioned only ten times. Labor? Nine.

As scholar Rene Rojas observes, working people in Chile desired universal economic rights and a progressive social contract. Contra conservatives, they wanted sewer socialism. What they got instead was cultural revolution, a charter far outside their Overton window. In response, they punished the delegates by voting down the constitution last week, with over 60% saying no. It didn’t help that conservatives spread fake news about what the draft contained. Yet it’s a fact that the Left overplayed its hand and shot itself in both feet by prioritizing identity and underdelivering on economics. Now the Right has the momentum, and the fate of the constitution is unclear. A golden opportunity to break from the legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship was squandered, and for that the Left has only itself to blame.

There’s a lot to learn from Chile’s story. One of the lessons is the importance of style. As Freddie deBoer writes on his Substack, voters want “normie politics.” That is, policies pitched in a way that makes them sound commonsensical and mundane. By “normie,” he doesn’t mean neoliberal centrism—the failed ideas of Bill Clinton or Mitt Romney. He means, rather, leftist policies that are couched in folksy garb:

By normie politics, I mean a politics that plays to the electorate’s sense of normalcy and which assuages their fundamental fear of change through symbol.

Symbol is the key word here. As I mentioned last time, people respond to candidates on a gut level. We all do. We base our political preferences off how a candidate makes us feel, and this has everything to do with how they look, talk, and behave on a corporeal level. A picture’s worth a thousand words, and the image of a candidate conveys symbolic meaning. DeBoer highlights John Fetterman of Pennsylvania as an example. Fetterman hails from the upper-middle class and earned a graduate degree in government from the Kennedy School at Harvard. Yet, as mayor of rust-belt Braddock, he’s adopted a grunge aesthetic and biker wardrobe that accents his goatee and shaved scalp.

Combined with a populist message out of the Sanders playbook, this everyman image has catapulted him ahead of his far-right opponent, Dr. Oz. FiveThirtyEight projects him winning by ten points right now, in a state that went for Trump in 2016 and barely flipped to Biden in 2020. That’s how you play smart identity politics. “Looking like John Fetterman and calling for Medicare for All,” deBoer says, “has a lower degree of difficulty than doing so when you look like a snide recent graduate from Brown.” It’s not about abandoning the concerns of identity groups. Rather, it’s about crafting a message that appeals to common hopes, dreams, and aspirations—the way the same-sex marriage movement did. DeBoer sums it up well:

Traditional identitarian concerns can be overcome through a concerted effort to appear normal. Barack Hussain Obama overcame his exotic name and background to cruise to two presidential elections. I am thoroughly convinced that, say, a Black former ironworker from the decaying small-city areas of Ohio who talked about shared sacrifice and a return to decency could dominate among Trump voters, regardless of his positions on most issues of controversy, if he was shameless enough about invoking the good old common sense of the past.

As observers like Brooks and Andrew Sullivan have noted for some time, the sweet spot in American politics at present is economic populism and cultural moderation. “If I were a cynical political operative who wanted to construct a presidential candidate perfectly suited for this moment,” the former writes, “I’d start by making this candidate culturally conservative. I’d want the candidate to show by dress, speech and style that he or she is not part of the coastal educated establishment. I’d want the candidate to connect with middle- and working-class voters on values and to be full-throatedly patriotic.” In other words, not Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, or Gavin Newsom. He goes on:

Then I’d make the candidate economically center-left. I’d want to fuse the economic anxieties of the working-class Republicans with the economic anxieties of the Bernie Sanders young into one big riled populist package. College debt forgiveness. An aggressive home-building project to bring down prices. Whatever it took. Then I’d have that candidate deliver one nonpartisan message: Everything is broken. Then he or she would offer a slew of institutional reforms to match the comprehensive institutional reforms the Progressive movement offered more than a century ago.

He ends by saying he wants a modern Theodore Roosevelt, which doesn’t exactly fit the sartorial bill—Roosevelt, like his cousin, Franklin, dressed as the patrician aristocrat he was. Yet the overall point is good, and the Left should take heed. Brooks’s policies are too milquetoast for his own prescription. But he and deBoer are correct when it comes to identity. I’d go further: I think the Left needs more white working-class men to be its public face. That’s right. Its movement is a multi-ethnic coalition, but its messengers should be of the Fetterman ilk. Such symbolic candidates would scramble the emotional response of voters, in a positive way.

Think, for instance, of Richard Ojeda. Ojeda grew up in the town of Logan, West Virginia, population 1,400. “Where I come from,” he says, “when you graduate high school, there’s only three choices—dig coal, sell dope, or join the Army. And I chose the military.” He served 25 years in the Army, rising from the ranks of the enlisted all the way to Major. He did multiple combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, by his own count almost dying five times—from an IED, mortars, and Taliban gunfire. He was awarded the Bronze Star twice for valor, and earned his BA and MA while in uniform. His patriotism’s unimpeachable, and his hyper masculinity blunts all charges of being a liberal squish.

In 2014, he entered West Virginia politics as a Democrat and won a state Senate seat. He championed striking teachers, wage increases, and legalized weed. To this populist platform he brought a pugnacious, profane style that fit the state’s Appalachian culture. He looks and talks like a hillbilly jarhead, “JFK with tattoos and a bench press,” as Politico put it. “I don’t give a shit who you are,” he told Michael Moore. “I’ll fight you in the damn street right now.” He lost his 2018 bid for Congress, 44% to 56%. But this was a 32-point improvement from the previous election, in a deep Trump district. According to FiveThirtyEight, he outperformed his district's partisan lean by 25%, the strongest showing that year for a non-incumbent.1

Don’t get me wrong. Non-white candidates can do well as leftists, I believe. Andrew Yang comes to mind. Yang’s an Asian American who went to Harvard, worked briefly on Wall Street, and became a tech entrepreneur. When he ran for President in 2020, he wore a slick blazer and generated dank memes online. None of that screams “populist.” But he consciously spent time with blue collar workers in post-industrial towns and advocated egalitarian policies like universal basic income, post office banking, and Medicare for All. While he proudly spoke about his ethnic heritage when asked, he didn’t run on his identity. As a result, he became a sensation among white working-class voters, and his campaign outlasted many of his centrist competitors.

I’m not saying the demands of particular identity groups should be abandoned. I’m simply saying that the Left can’t lead with those issues. It must prioritize universal values and policies. If it does that, of course, marginalized communities will benefit, just like in the New Deal. The Right gets how to play identity politics. It’s taken pains to recruit women, Blacks, and Hispanics to be their standard bearers—the very kinds of people you don’t associate with Republicans. Democrats must follow suit. It would help, too, if their candidates were practicing Christians open about their faith. That’s because, despite the secularization of society, Americans still connect politics to an overarching moral narrative that derives from the Bible. It’s called civil religion, and it makes for my last prescriptive point.

II. Prophetic Republicanism

American fascism takes the form of white Christian nationalism. In this perversion of religion—my own faith—the political movement seeks a theocracy and rewrites America’s history to buttress it. The Founding Fathers, it claims, were divine beings inspired by God to write the Constitution and who wanted to build an explicitly Christian nation. Some in the Left, on the other hand, preach the opposite—a radical form of secularism in which all mention of faith must be banished from the public square. The American Revolution was a product of the Enlightenment, they argue, and many of the Founders were deists skeptical of organized religion (if not, as in the case of Thomas Paine, outright atheists).

Between these camps lies a third, venerable tradition: civil religion. Made famous by Robert Bellah in the 1960s, it encompasses the implicit religious values of a nation, as expressed through public rituals; symbols (e.g., the flag); and ceremonies at hallowed places (such as monuments, battlefields, or national cemeteries). It includes such practices as the invocation of God in political speeches; the veneration of past leaders and use of their lives to teach moral ideals; and the honoring of veterans and casualties of war. The singing of the national anthem; parades on the 4th of July; and the Presidential Inauguration are all part of this tradition.2

In 2017, Philip Gorski of Yale published a comprehensive study of the idea, American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present, which everyone on the Left should read. He enumerates eight basic tenets of civil religion:

Civil religion stands against both religious nationalism and radical secularism. It is a moderate form of secularism and a liberal form of nationalism.

It believes, on the one hand, that church and state should not become entangled. But on the other, it believes we can’t—and shouldn't—take religion entirely out of politics or vice versa.

It insists that the American project has a moral and spiritual core.

It values American culture and institutions enough to cherish and defend them but without succumbing to the hubris that America is always and everywhere a force for good in the world.

It’s neither idolatrous nor illiberal.

It recognizes both the sacred and secular sources of the American creed.

It provides a political vision that can be embraced by believers and non-believers alike.

It’s capacious enough to incorporate new generations of Americans.

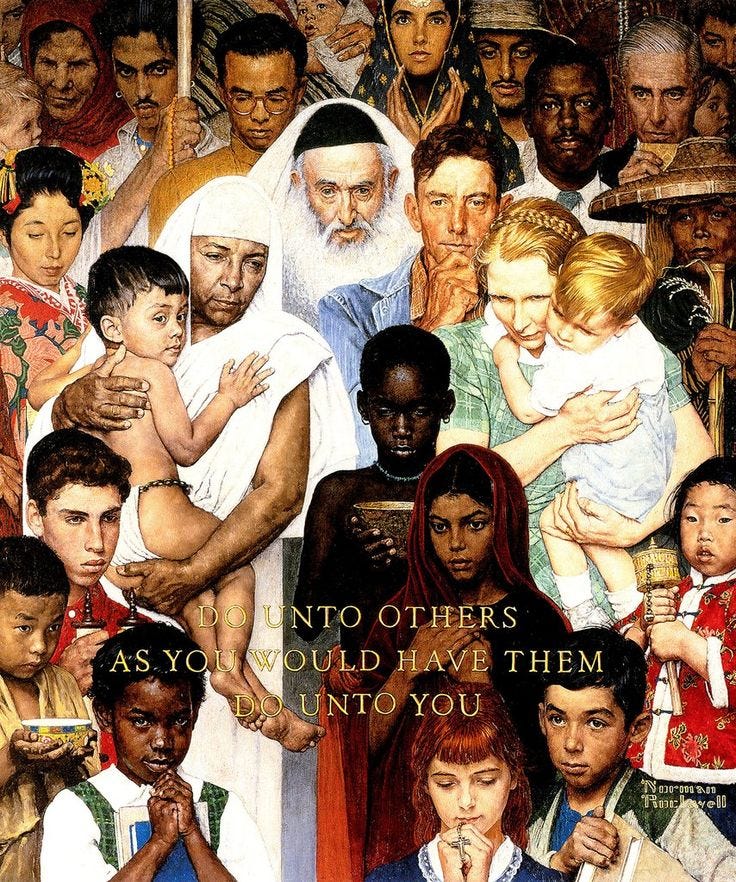

At the core lies a national narrative or myth—the American Dream. As Gorski says, the real American Dream is not about a house in the suburbs with a white picket fence. Rather, it’s the dream of a righteous republic, a free people governing themselves for the common good. This image draws deeply from the Hebrew prophets to create what he calls “prophetic republicanism.” Prophetic republicanism combines the Biblical idea of a righteous people with the modern political theory of republicanism. We often talk about the United States as embodying liberalism, but Gorski points out that the ideology of the Founders was only one-quarter liberalism, and three-quarters republicanism.

The key rhetorical device of prophetic republicanism is the jeremiad. This exhortative form of address has a three-part structure: first, it recounts the people’s original mission and identity. Secondly, it offers a litany of their collective failures and impending doom. And, thirdly, it issues a call to social renewal. Classic jeremiads include Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852); Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address (1865); and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech (1963). Such texts express a kind of covenant theology from the Exodus story, in which God chooses one nation to model justice and holiness to the world—“not for special blessings,” says Gorski, “so much as for special judgment.”

The story of Exodus, recall, is the forging of a multitude of lost souls into the nation of Israel—one people emerging out of many tribes, in right relationship with each other and with God. The purpose of the nation is to be a light to the world by maintaining this horizontal and vertical communion. To achieve such an end, social justice and worship of Yahweh must go hand in hand. These days, liberals get nervous about applying covenant theology to America. It sounds like idolatry; after all, the true inheritor of the Exodus story is the Christian Church, not the nation-state. Covenant theology isn’t inherently nationalist, but it can become so in the hands of bad actors (like Marjorie Taylor Greene). But when done right, it can be very effective, as Dr. King demonstrates:

God somehow called America to do a special job for mankind and the world. Never before in the history of the world have so many racial groups and national backgrounds assembled together in one nation. And somehow if we can’t solve the problem in America, then the world can’t solve the problem, because America is the world in miniature and the world is America writ large...The judgment of God is upon us. We must either learn to live together as brothers and sisters or we are all going to perish as fools.

The difference between Christian nationalism and civil religion is that between metaphor and simile. A simile says one thing is like another thing. A metaphor says one thing is another thing. Christian nationalism employs the latter: America is God’s chosen nation. Civil religion says the former: America is like God’s chosen nation. It uses its simile to stimulate a mental analogy and motivate reformist energy. Christian nationalism, on in contrast, means its metaphor quite literally: as a way to immunize the nation from legitimate critique and punish gadflies. The latter is a diabolical twist of the former. (Diana Butler Bass has a lucid dissection of the difference over at her Substack, The Cottage.)

Here’s an example: The most famous trope in American political discourse—the city on a hill—derives from John Winthrop’s “A Model of Christian Charity” (1630). If you read the text closely, the Puritan minister doesn’t say his community is a city on a hill. Rather, that they should be like one: “We must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill,” he writes (emphasis mine). He calls the people to humility in the face of God’s covenant, a relationship that, drawing on the Book of Deuteronomy, was conditional: If we create a just society, then God will bless us and our descendants. But if we fail—if we live selfishly and neglect the commonweal—God will withdraw his favor and curse our line. Winthrop puts the matter thus:

Now the only way to avoid this shipwreck, and to provide for our posterity is to follow the counsel of Micah, to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God. For this end, we must be knit together, in this work, as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of other’s necessities.

As Gorski relates, conservatives like Ronald Reagan hijacked this image for ulterior ends. Instead of humility, Reagan used the line (to which he added the gratuitous adjective shining) to encourage pride in American greatness—which is, literally, one of the seven deadly sins. He also dismissed the corrupting effects of luxury and wealth, ushering in a decade in which greed was good, only the welfare state bad. This vision—carried on by his fascist heirs—was a complete perversion of Winthrop’s. “The care of the public must over sway all private respects,” the minister told his flock, “by which, not only conscience, but mere civil policy, doth bind us. For it is a true rule that particular estates cannot subsist in the ruin of the public.” That’s a rebuke of neoliberalism if ever there was one.

Politically, prophetic republicanism asserts five key ideas:

Human Nature. Human beings are inherently social. We instinctively seek the company and approval of other people, not just for instrumental reasons of economic exchange, and naturally form self-governing communities. A republic is the logical result of this disposition.

Freedom. Far from licentiousness or libertarianism, freedom is a complex state that requires four underlying conditions:

Not being a slave, i.e., not being subject to the arbitrary will of another person.

Personal Virtue: Shaping one’s passions so one naturally desires what is good and just, and dislikes what is base and selfish.

Civic Virtue: Citizenship takes ethical and practical skill, a knowledge of what is worthwhile and how to attain it. Free institutions are inherently fragile and cannot survive long without a citizenry animated by virtue.

Equality: A righteous republic must create the conditions for the advancement of as many people as possible. It does so by democratizing society, eliminating social and economic inequalities. It must protect society from the concentration of wealth into the hands of a small set of oligarchs.

Constitutional Balance. Only a balance of power among different social groups can prevent abuses. Unless checked by other groups, a dominant group will find ways to subvert laws and institutions for its own gain and elevate its interests above the common good.

Historical Time. Time is a progressing spiral, neither an uninterrupted linear evolution, nor an eternal cycle of recurrence. Moral advancement is possible, but it involves conflict and regression. Our mandate is to realize more fully the meaning of our founding principles. When we act righteously as a people, we move upward and outward toward higher ends and greater inclusivity.

Corruption. Republicanism believes corruption is cultural—the putting of self-interest before the common good. It’s inevitable and natural, like the decay of organic matter. We can’t stop it, but we can guard against its pernicious influence. The source of corruption is the triple threat of idiocy (not participating in civic life), barbarism (the reduction of public affairs to technocratic efficiency), and tribalism.

Gorski concludes by calling the next generation to appropriate prophetic republicanism for our time. At his best, Barack Obama did this, and it was key to inspiring so many to his banner. Doing so again requires that we remember the real American Dream, and don’t succumb to Christian nationalism or radical secularism. That we acknowledge how many have been excluded from the dream and still are. And that we strike out anew to redeem the dream for our time—to breath new life into the vision of a righteous republic and invite those left out before. Gorski closes with stirring words:

The dream will never be fully realized, by this generation, the next, or any other, because the American republic is built with the crooked timber of a fallen humanity, just like any other polity. Still, each generation of Americans is responsible for trying to build out its walls and make them straight, to the best of its abilities.

III. Christian Democratic Socialism

Socialism, like fascism, is as American as apple pie. I place myself in the broad tradition of Christian democratic socialism. To my mind, this movement carries on the best of America’s civil religious heritage. Indeed, Dr. King himself was a socialist. (Gary Dorrien has a fascinating history of the Black social gospel over at Commonweal.) Other figures include Rev. George W. Woodbey, Dorothy Day; Norman Thomas; and John Cort. Representatives today would be leaders like Dr. Cornel West, Rev. William Barber, and David Bentley Hart (see especially Hart’s essay “Three Cheers For Socialism”). Socialism isn’t a personal preference or individual choice, for me—it’s a response to the revelation of God in scripture, the carrying out of the Lord’s will that all peoples enjoy justice and life in his good creation. Understood correctly, it flows from a transcendent moral order that binds us together.

There’s talk among some leftists about emphasizing atheism. This would be political suicide. Dr. West puts it succinctly: the Left needs Jesus. “As a Christian, I think everybody could gain much by having a relationship with Jesus,” he says. “But I think the left can teach Christians like myself very much in terms of their willingness to speak in a courageous way to the ‘least of these,’ to echo the 25th chapter of Matthew: the poor, the orphan, the widow, the exploited.” Likewise, David Alberston and Jason Blakely argue that utopian Christian communities like Day’s Catholic Worker offer important lessons for progressives. “Today’s democratic socialists,” they write, “should join communities of radical belonging with the poor.” If they don’t, they risk drifting toward false prophets—“a political hero, an ideological test, an abstract vision of the future, or revenge against opponents.”

This brings us to the heart of the Gospel. In the Acts of the Apostles, the evangelist paints a portrait of the Jesus community in the wake of the resurrection. It’s an astonishing picture:

The whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. With great power the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need.

On the face of it, this is a communist society. It’s voluntary, of course, and the text is probably an idealized image of the post-Easter church. But its animating idea is one made famous by Marx and Engels: From each according to his ability, to each according to his need. As Thomas Merton observed, this is the ethos of monastic communities. I view democratic socialism, then, as the attempt to apply the Gospel to modern political economy. Reading the principles of Catholic social teaching, for example, you can’t help but see how close they come to socialism.

The radical thrust of the Bible is a point that someone like Brooks fails to appreciate. He’s a booster of the Exodus narrative for its unifying message. But it’s worth remembering the full arc of that narrative: before God forms the Israelites in the wilderness, he first overthrows Egypt, the prototype of all demonic empires. It’s not a gradual, mealy-mouthed approach. It’s a catastrophic upheaval of Pharaoh’s regime of terror, plunder, and enslavement, culminating in the death of the first born of every Egyptian household. The idea, which continues through the Prophets, is clear: we can’t become the People of God until the yoke of bondage is cast off the poor.

The New Testament is no less uncompromising. Jesus, like God, is a revolutionary. He rejects religious nationalism, which the Gospels say is satanic. His first public utterance pronounces good news to the poor, freedom for captives, and liberation of the oppressed. He rebuts the scarcity mentality of selfishness with a one of hospitality, abundance, and generosity. He castigates the rich and powerful with hardness. Before he’s even born, in fact, his mother proclaims that God, through her son, will lift up the lowly and send the rich away empty. This is a vision of world turned upside down, bottom rail on top.

Far from preaching a capitalist work ethic, Christ taught his disciples that seeking wealth is intrinsically evil. This denunciation of greed continues through the Gospels into the Pauline epistles, the Letter of James, and 1 Timothy. As Hart observes, “most of us would find Christians truly cast in the New Testament mold fairly obnoxious: civically reprobate, ideologically unsound, economically destructive, politically irresponsible, socially discreditable, and really just a bit indecent.” He sums up the way of the primitive church in stark terms:

The first, perhaps most crucial thing to understand about the earliest generations of Christians is that they were a company of extremists, radical in their rejection of the values and priorities of society not only at its most degenerate, but often at its most reasonable and decent. They were rabble. They lightly cast off all their prior loyalties and attachments: religion, empire, nation, tribe, even family.

Maybe that should be the socialist message: Make America a Rabble Again. Paradoxically, if we can tap into the religious strain of the radical tradition, we might appeal to the authority, loyalty, and purity tastebuds of conservative voters. Socialism, we can say, is how we return the country to faith, family, and freedom and thereby secure the blessings of liberty to us and our posterity. With civil religion as our guide, we have a fighting chance of achieving, as Lincoln prayed, a just and lasting peace—among ourselves, and with all nations.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Ojeda#2018_U.S._House_campaign

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_religion