[This post is Part V of a series. Here are links for Part I; II; III; IV; VI; VII; and the Epilogue.]

I. Introduction

In the wake of the FBI search of Donald Trump’s estate on Monday, the phrase #NationalDivorce was trending briefly on Twitter, as the Right threatened secession and (more) uprisings. In a future installment on the American Nations, I’ll sketch out some possible futures for the U.S. federation: how the various nations might re-arrange (or dissolve) our national condominium. For today, I want to piggyback on where I ended my last post and discuss how the Left can become competitive again in national elections, using the American Nations as its guiding concept.

You know by now that I think elections are a poor, corrupt, oligarchic way to select rulers. They reward spectacle, tribalism, and emotion, not deep thinking or good policy. The pathologies of our campaign industry are too numerous to enumerate. But for now, the Left has to work within this byzantine system, even as it strives for a real democracy. So, let’s outline a strategy to win back the various nations we’ve lost to the Right. To recap, here’s my three-point plan:

Learn the cultural values of the Midlands, Yankeedom, and El Norte and connect them to leftist ideas.

Make residents in the rural counties of those regions feel heard and respected.

Deliver a Sanders-style message of cultural moderation and economic populism through stories that will resonate emotionally.

To these initial three, I want to add two more:

Play smart identity politics.

Master the rhetoric of prophetic republicanism.

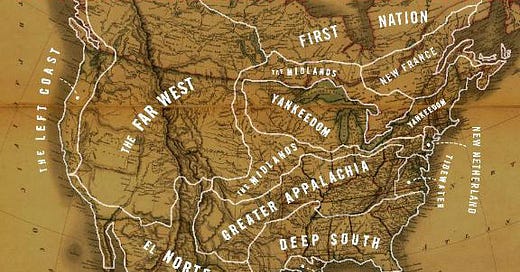

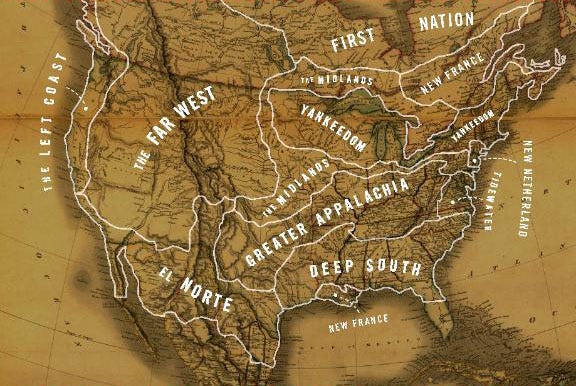

Today, I’m going just to unpack the first point: Learn the cultural values of the Midlands, Yankeedom, and El Norte and connect them to leftist ideas. As we’ve learned from Colin Woodard, each of the various ethno-nations within the United States is animated by a distinct regional ideology. Residents in these places cast their ballots based on that identity. This is a hard lesson for the Left to grasp, as it wants to reduce political decisions to class, race, and material self-interest. These play a role, for sure, but—contra Marx—they’re not as determinative as culture. Hence the Left’s constant refrain: “What’s wrong with Kansas?” That is, why do white working-class Americans consistently support the Right, which has waged war on labor for decades? The answer is that it’s not the economy, stupid: it’s values.

To become competitive nationally, the Left needs to learn the cultures of the nations and marry its message to them. In other words, it needs to know which nation it’s operating in at all times—literally at the county level—and cast leftist ideas in the language, symbols, and ethos of that region. The three key nations the Left must focus on (as I explained last time) are the Midlands, Yankeedom, and El Norte. The good news is that Bernie Sanders played very well in these counties in the Democratic primaries of 2016 and 2020. The Left just needs to make explicit the lessons of his campaign.

II. The Midlands

We talked about the Midlands at length last time, so I won’t dwell on this region today. Its communitarian ideology preaches a gospel of pluralism, equality, and fairness. Themes like neighborliness, humility, and the common good resonate here. When speaking to the Midlands, socialists should emphasize how they favor democracy in both the economy and politics; how they seek to level the playing field to give everyone an equal shot; and how they want to build stronger connections in local communities—to their towns, their families, their vocations. In short, socialists want to make America a neighborhood, where no one goes it alone.

III. Yankeedom

With its values of education, community empowerment, and broad participation in government, Yankeedom makes a natural fit for socialist ideas. Woodard describes the region as follows:

Yankees would come to have faith in government to a degree incomprehensible to people of the other American nations. Government, New Englanders believed from the beginning, could defend the public good from the selfish machinations of moneyed interests. It could enforce morals through the prohibition or regulation of undesirable activities. It could create a better society through public spending on infrastructure and schools. More than any other group in America, Yankees conceive of government as being run by and for themselves. Everyone is supposed to participate, and there is no greater outrage than to manipulate the political process for private gain…With its crusading utopian agenda, Yankeedom is on a quest for betterment of the “common good,” seen as best achieved through the creation of a frugal, competent, and effective government supported by a strong tax base and able to ensure the availability and prudent management of shared assets.1

What’s happened, as I pointed out last time, is that folks in rural Yankeedom feel abandoned by the government—they feel passed over in favor of urban elites. Winning back their allegiance will require a sustained effort that I’ll describe in a subsequent post. For guidance, I suggest everyone on the Left read Chloe Maxmin and Canyon Woodward’s new book, Dirt Road Revival. Maxmin is a Millennial and veteran of the Sanders’s campaign who won state office in the most rural, Republican district of Maine. As she tells it, the Left needs to relate to these voters based on values, not partisanship. Specifically, she mastered the “moral foundations” insights of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. Rural folks feel part of ‘thick’ communities on which they build their identity. In these conservative matrixes, in-group/loyalty, purity/sanctity, and authority/respect matter more than in liberal enclaves. Maxmin incorporated these themes into her campaign:

We appealed to the In-group foundation by translating Chloe’s deep commitment and love for home as “loyal representation” and prominently centering the fact that she was raised in Lincoln County. We appealed to the Authority foundation by framing Chloe’s vision for the future as the key to protecting the traditions and culture of the past. “I’m running for State Senate knowing that if we fail in the future, we are certain to lose what we cherish of the past,” read her first mail piece of the campaign. “Together we can ensure that District 13 is a resilient community. That means the strength to protect our past, feel safe in the present, and stay strong in the future. It’s about withstanding new challenges while holding on to what makes our community special.”

‘Resilience’ was the key theme of her platform. She ran on building resilient local agriculture, small businesses, and public education. Other policies included universal broadband Internet access; accessible and affordable healthcare (highlighting mental health and the opioid epidemic; access to transportation; and strengthening Social Security. This platform arose from her conversations with the community and reflected their values.

Key to her effort was using rhetoric, language, and messaging that would get the Left’s ideas across to these rural voters. As she relates, thanks to years of right-wing media,“there are certain phrases or ideas that are nonstarters in many rural communities.” Her campaign found it more productive to avoid charged labels and discuss ideas instead:

For example, we could often reach someone who might be up in arms over the term ‘feminism’ but agrees with the need to eliminate the wage gap and ensure equal pay and opportunity. Many people in our community want affordable healthcare, but they don’t want to talk about Medicare for All because relentless right-wing messaging has made these words toxic. So many of the values and ideas that we talk about can resonate in rural America if we can translate them into a rural context…When Chloe was door-knocking in 2018, she rarely heard folks talk about climate change. But she did hear people talk about the need for sustainable industry, good jobs, ice fishing on the lakes in the winter, rain for the farms in the summer…The result was a climate bill that was starting a conversation about climate change through the lens of labor.

I’ll have more to say about Maxmin’s strategy for winning over backcountry voters next time. But for now, these make for helpful examples of how to translate the Left’s ideas into a rural Yankee idiom.

IV. El Norte

I’m going to spend a chunk of time here. The Left must understand this region, since it’s fast becoming the kingmaker in national elections. Woodard writes that “among Mexicans, norteños have a reputation for being more independent, self-sufficient, adaptable, and work centered than their central and southern countrymen.” I’ve stated before that the ideology of El Norte is essentially Christian Democracy. As Michel Gurfinkiel relates, while unfamiliar to Americans, this politics has a long and proud tradition, especially in Europe and Latin America. In the former, it rebuilt the shattered societies of postwar Germany and Italy, often working in coalition with the Social Democrats. Udi Greenberg summarizes its major tenets in his review of Carlo Invernizzi Accetti’s book:

First, the principle of ‘subsidiarity.’ Christian Democrats believe in a social order made of layered associations—such as families, professions, and religious organizations—which complement each other. For this universe to function properly, people must honor their multiple and simultaneous solidarities to these many communities. This vision of human nature and society rejects both individualism (with its disregard for traditional bonds) and collectivism (which subjects one’s identity to one group, such as nation, race, or class). The purpose of politics is to secure this social order.

Secondly, free enterprise mitigated by regulation and welfare programs. The Germans described this approach as the “social market economy.” It worked in concert with American-controlled Keynesian organizations, above all the Marshall Plan. In practice, this means that Christian Democrats accept the sanctity of private property and largely (with some variations on specifics) lean toward the free market. They’re not proponents of laissez-faire and helped establish substantial welfare programs. But they oppose more radical distributionist schemes like a jobs guarantee, nationalization of key industries, or government-provided health care.

Thirdly, the rule of law and support for “traditional” institutions (including the monarchy, where it still exists). The widespread postwar desire to return to normalcy reinforced the conservative platforms of Christian Democratic parties. While they defend the legal parity of all, they also believe in “natural” inequality and that order requires economic and social hierarchies. Socioeconomic distinctions, in fact, are a necessary dam against modernity’s relentless pressure to impose sameness in everyone. States must protect traditional communities (for example, by defending family authority over children’s education) and secure their citizens’ autonomy from collectivist demands.

Fourthly, pro-family policies, which include direct government subsidies for parents, subsidized housing, support for family businesses, support for religious school networks, a conservative stand on sexual norms, policies curtailing birth control, and prohibition of abortion and even divorce.

Fifthly, hatred of atheism, which Christian Democrats have countered by investment in Christian education and the celebration of Christianity in public. Europeans had replaced the worship of God with a hubristic embrace of materialism. During the Cold War, Christian Democrats saw communism—with its open embrace of atheism—as the era’s most urgent threat. They aligned themselves with the United States, armed their countries to the teeth, and engaged in relentless anti-communist propaganda campaigns.

As you can tell, Christian Democracy (and, by extension, El Norte) is a centre-right ideology that values faith, family, entrepreneurship, and tradition—a natural fit for the Republican Party. Ironically, though, Democrats have long held sway here because of the GOP’s virulent xenophobia. But we noted last time the massive shift of rural norteños to Trump in 2020. What happened? The firm Equis has done a deep dive into the data and explains it in three takeaways (the full report is here):

First, the COVID lockdowns created fears for the economy among conservative norteño voters. Since they attributed the lockdowns to the Democrats (and, by extension, Joe Biden) and associated Donald Trump with economic freedom, these voters felt increased “permission” to vote for the 45th President—even though they disliked everything else he did. As the report says, “While Trump’s approach to border spending (not the wall) earned majority support among Latinos, he lost even the conservatives on family separation. But family separation was not front-and-center by the end of the election. Reopening the economy—one of Trump’s most popular planks with Latino voters—was.” The economy and COVID had become Latino voters’ top priorities in 2020—at the expense of immigration.

Secondly, the Right saturated El Norte with TV, radio, and social media ads—a campaign blitz that the Democrats failed to fight. A sizable number of norteños feel taken for granted by the Democrats anyway, and the lack of physical presence by Biden and other high-profile Democrats in this region reinforced that sensibility. (In contrast, Bernie Sanders heavily courted Latinos in Nevada, and they catapulted him to victory in the caucus.) The moral of the story: uncontested communication and voters feeling unheard had, as always, a major impact.

Thirdly, the right-wing attack on socialism broke through, creating space for conservative norteños to defect from the Democrats (and not just Cuban Americans in Florida). Concern about socialism seems to be generated in part by uncontested propaganda in isolated media ecosystems—what’s sometimes reduced to “disinformation.” And it centers on Latino voters who most believe in social mobility through hard work—consistent with the idea that, in the right-wing narrative, the true opposite of socialism is the American Dream. While the socialism attack rings various bells, the through-line among those concerned is a worry over people becoming “lazy & dependent on government,” by those who highly value “hard work.”

The first two points can be corrected rather easily. The Left must mount a massive hearts-and-minds campaign in this region over months and years, Sanders style, to counter right-wing messaging. Its leaders need to be physically present there in a visible, consistent manner day in and day out—not just during election season. When it comes to the economy, the threat of more lockdowns is over (for better or worse) and the Left can counter the sting of inflation with populist proposals like price controls, wealth taxes, democratic planning, public investment, and downward redistribution.

But it’s that last point that’s troubling. Conservative norteños—especially under the influence of propaganda—consider socialism the enemy of the American Dream. Given that El Norte is an inherently centre-right region, this fear scans. Norteños still believe—by wide margins—that the Democratic Party is better overall for Latinos; that it’s the party of fairness, equality, and opportunity; and that it cares about people like them. 56% say, in contrast, that the GOP benefits big corporations, not everyday people. At the same time, Democrats and Republicans are running even among norteños on the questions of which is the party of the American Dream, of workers, and of religious values.

The Left thus must work overtime to reframe both socialism and the American Dream, demonstrating how it’s the party of workers, of families, of faith—and the GOP the party of oligarchs. It must emphasize how giant corporations cheat their way to wealth and exploit everyday people, while the Left’s policies help hard working folks and allow wage earners to rise. It can argue that public goods like healthcare, housing, and retirement plans will take the burden off small businesses. It should tout pro-family plans like a universal child allowance, family leave, public child care, and free pre-k. And it must explain that government investment enhances, not hinders, individual innovation.

Finally, it has to wrap these policies in the language of progressive Christianity—the biblical idiom of the Kingdom of God, the Good Samaritan, and the Love of Neighbor. That is, it must reclaim the American Dream in terms of civil religion. (More on this in a subsequent post.) It’s possible for the Left to do this—again, Sanders proved so repeatedly. And if it means never using the actual word socialism, so be it.

V. Immigration: The Third Rail

What about immigration? This, of course, is the elephant in the norteño room. As we know, American fascists—like their compatriots in Europe—have made immigrants their preferred bogeyman. Fear of newcomers is a canard as old as the republic itself, and utterly unfounded. As Woodard points out, the cultures of the various American Nations have incredible staying power. Between 1820 and 1924, three large waves of immigrants arrived on these shores. And yet—curiously—the foundational regional cultures of America remain in place. True, in a couple of places the original ethno-nation was displaced by a flood of new arrivals—for example, the Dutch in upstate New York as Yankees moved out of New England. But those are exceptions.

Instead of diluting and changing the nations, immigrants reinforce and enrich regional identities. My ancestors—poor Irish and Italians—were viewed with the same suspicion as destitute refugees entering America today. They were considered alien threats poisoning the body politic. And yet within a generation, their descendants assimilated to the regions they inhabited. Growing up in upstate New York, my family was indistinguishable in values and culture from the Yankees of the eighteenth century. Woodard puts it thus:

Immigrant communities might achieve political dominance over a city or state (as the Irish did in Boston or the Italians in New York), but the system they controlled was the product of the regional culture. They might retain, share, and promote their own cultural legacies, introducing foods, religions, fashions, and ideas, but they would find them edified overt time by adaptations to local conditions and mores. They might encounter prejudice and hostility form the “native” population, but the nature and manifestation of this opposition varied depending on which nation the natives belonged to. Immigrants didn’t alter “American culture,” they altered America’s respective regional cultures.

Since 1965, a fourth wave has flowed into the U.S., elevating the percentage of foreign-born in the population from 4.7 in 1970 to 13.7 in 2018. That’s still below the all-time peak in the early 20th century, as Woodard explains:

Despite the scale of immigration, newcomers were always a minority. The proportion of foreign-born remained at about 10 precent of the U.S. population throughout the period, peaking at 14 percent in 1914. Its cumulative effect was important but not overwhelming. Even after adding together all immigrants between 1790 and 2000—66 million altogether—and their descendants, demographers have calculated that immigration accounts for only about half the early-twenty-first-century population of the United States. In other words, if the United States had sealed its borders in 1790, in the year 2000 it would still have had a population of about 125 million instead of 250 million. The 1820-1924 immigration was enormous, but it was never truly overpowering.

Enormous, but never overpowering. The same must be said today. In 2020, Pew Research Center released a report on immigration in 2020 that punctured a lot of myths. Did you know that since 2009, Asian immigrants have outnumbered Latinos almost every year? In 2018, 37% of immigrants were from Asia, compared to 31% from Hispanic countries. Asians are projected to be the largest immigrant group by 2055. Meanwhile, more Mexican immigrants are leaving the U.S. than arriving, as they seek to reunite with families on the other side of the border. The total number of immigrants will rise from the current 44.9 million to 78.2 million by 2065, but that will still amount to only 18% of the population—a percentage that lags far behind Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and many European nations.

As in the past, most of today’s immigrants settle in the same regions of the country they alway have: the ones that welcome newcomers. The above map shows that they move to the Northeast & Chicago (Yankeedom, New Netherland), southern Florida (Baja Florida), and the cities of California, Arizona, and Texas (El Norte). They avoid rural communities, especially the Deep South, Appalachia, and the Far West, which historically have been hostile to outsiders. There’s a great irony here: the American Nations most suspicious of immigrants hardly see them.

That’s to their detriment, in the end. Given the low birthrate across the country, and the brain drain of young people to cities, rural communities—and the entire nation—stand in dire need of new blood. America needs a great replacement—we’re literally dying. As Bill McKibben recently wrote in The New Yorker, local leaders who’ve awakened to this fact have intentionally brought in immigrants. Places like Utica, NY and Jefferson, Iowa have embarked on campaigns to recruit Latinos and refugees, with promising results. For all these reasons—and given the cultural resilience of the distinct American regions—I favor a policy of open borders. It makes sense on both humanitarian, political, and economic grounds.

And increased immigration is very popular. As the chart below illustrates, the vast majority of Americans have a positive view of immigrants. In fact, as another Pew study reveals, great majorities—including sizable numbers of Republicans—are sympathetic to unauthorized immigrants (67%); want to grant them legal status (67%); and think they mostly fill jobs Americans don’t want (71%). Since 2001, the share of Americans who favor increased legal immigration into the U.S. has risen 22 percentage points (from 10% to 32%), while the share who support a decrease has declined 29 points (from 53% to 24%). In fact, the share of Republicans who support decreasing the level of legal immigration has declined 10 percentage points since 2006 (from 43% to 33%), while the share who favor increased legal immigration has risen from 15% to 22%.

So, when you hear fascists like Tucker Carlson, or even respectable conservatives like Glenn Loury, Reihan Salam, and Andrew Sullivan, vent about controlling the “composition” of American society, just know that—however respectable they make it sound—these are classic xenophobic anxieties. Their views are out of step with most Americans, and have more to do with psychology than reality. Given that tens of millions immigrants—and certainly their children—have assimilated into the various American nations over two centuries, the fear of some “cultural revolution” occurring in the next is absurd. (Personally, I would like to see the culture of the Deep South change, but that’s for another day.) The only way to understand such rhetoric is as an irrational fear—explicit or subliminal—of demographic contagion. But being an American is not a matter of blood and soil. It’s a matter of values.

Yet that’s the problem: immigration triggers latent fascist tendencies in some people, and they’re highly motivated voters. High scores for aggression and authoritarianism on psychological tests correlate with hostility to immigrants (probably why the Deep South as a region is hostile to them). Demagogues like Trump exploit this “securitarian” mindset and drive an “immigrant threat” narrative in the media to gin up votes; Trump’s supporters had stark, negative views of immigrants.

When it comes to policy, among Republicans, 41% say better border security and stronger law enforcement should be the focus; just 12% say creating a way for those in the U.S. illegally to become citizens should be the main priority. 45% say that stronger law enforcement and a path to citizenship should be given equal priority. This concern for security animates conservative norteños, too. As the Equis report shows, Hispanics who live along the border are much more in favor than urban Latinos of border spending (61%-46%); limiting asylum-seekers (58%-45%); and increasing deportations (42%-34%). Since Trump was seen as the candidate of law & order, he played better among these voters (in combination with their economic views).

How should the Left deal with this higher desire for security among rural norteños? Sanders opposed open borders (wrongly in my view), but I don’t think the Left has to abandon this position in order to appeal to rural Latinos. More important, I think, is making them feel seen and heard, hitting the fairness and economic message, and combatting anti-socialist propaganda. But when it comes to the border and immigration, the Left needs to craft a message about how simplifying immigration will make everyone safer in the long run.

Contra conservatives like David Frum, the Left should not play into the Right’s narrative of a border crackdown. It has to set itself in stark contrast and reframe the narrative. But just as Maxmin did in Maine, it has to sell its policy in counter-intuitive terms: based on group loyalty, authority, and purity. This will be hard, given that conservatives tend to see undocumented migrants as an alien invasion that poisons “us” and subverts the law. But it can be done. At the same time, the Left should foreground the cruelty of the far-right’s family separation policy and similar plans. If it does these things in the coming decades, it can staunch the bleeding and win El Norte.

Colin Woodard, American Nations (p. 58; 281). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.