I.

In an essay for the January edition of Harper’s, Mark Edmundson makes a brazen claim: that philosophy is the cause of Donald Trump. Specifically, the school of thought known as Pragmatism. Given that Trump is a grotesque, vulgar, half-literate thug, ascribing his character to a rigorous intellectual tradition seems counter-intuitive, to say the least. On the one hand, it’s nice to see philosophy get discussed in a popular magazine, especially given the instinctive aversion to the subject in this country. On the other hand, though, it’s troubling that Edmundson would make it the scapegoat for such an imbecilic figure and his carnival of brutes. Is he right?

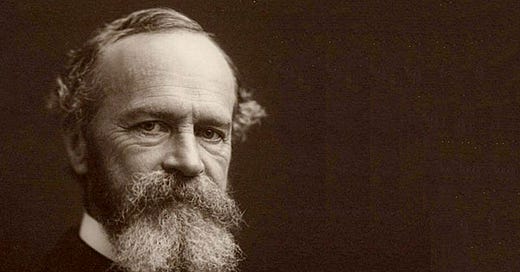

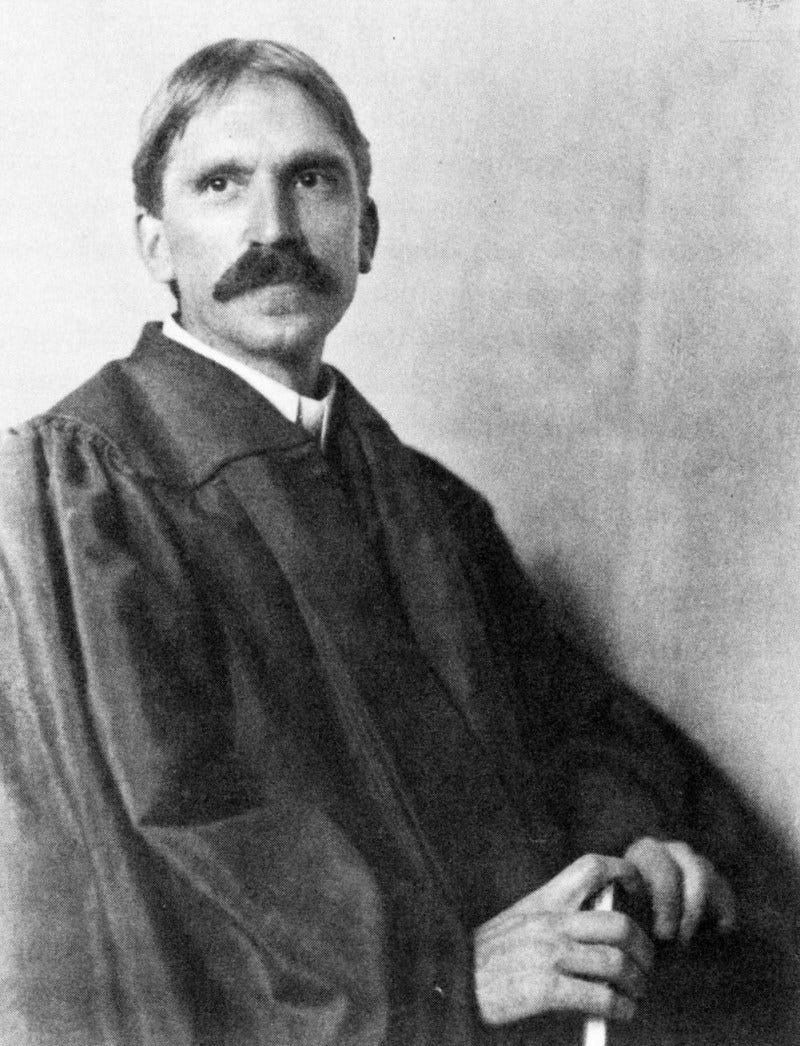

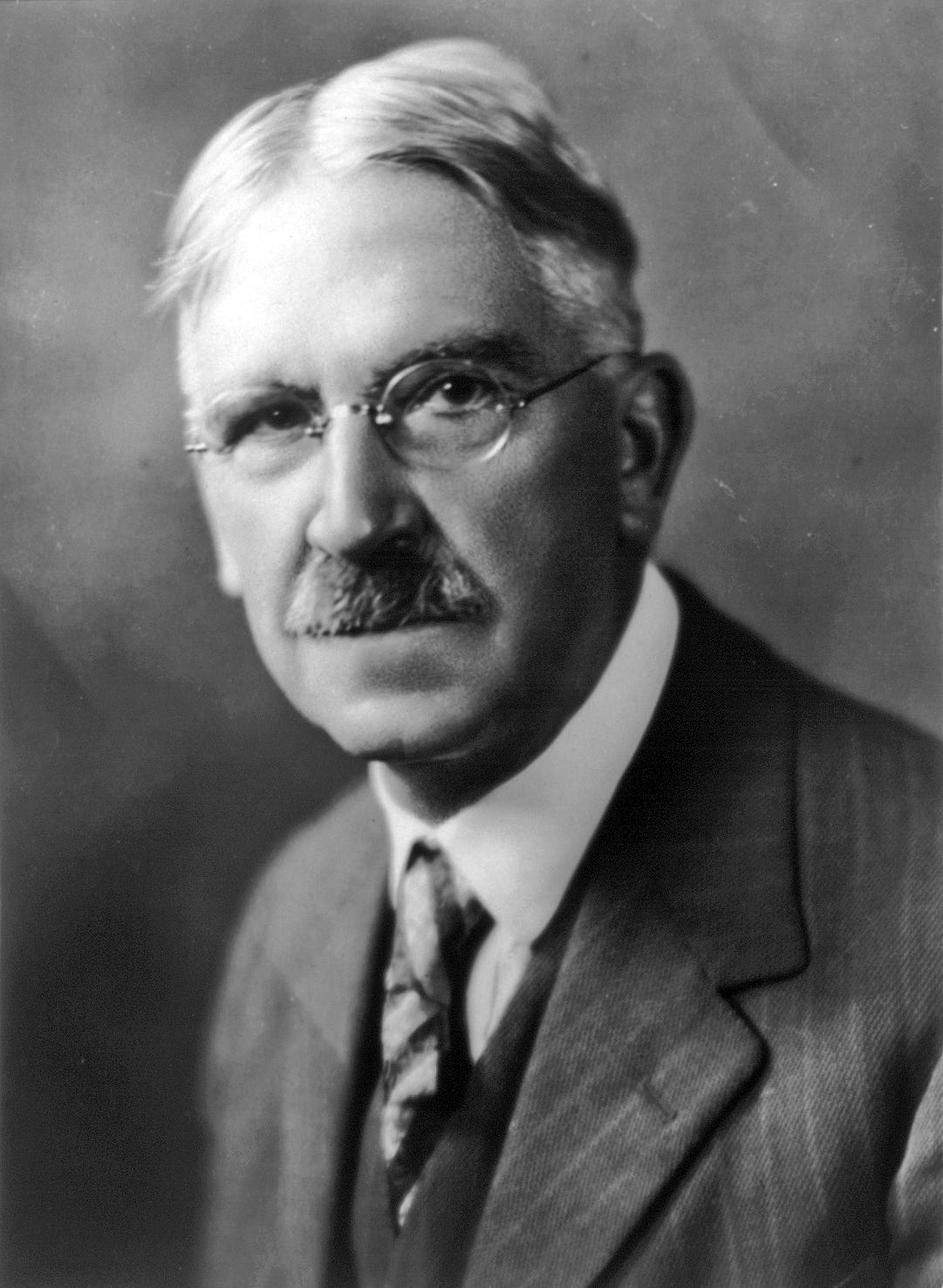

Pragmatism is the only original philosophical movement that America’s produced. It finds its roots in Emerson and flowered with a triumvirate of thinkers in the late 19th-century: Charles Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. George Herbert Meade, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Alain Locke were fellow travelers at the time. Prominent contemporaries include Richard Rorty and Cornel West, among others. It’s difficult to sum up the ideas of the original founders, due in part to the fact that they disagreed fiercely over just what they meant. They were part of Western philosophy’s ongoing attempt to reckon with and escape the mind-matter dualistic trap that Descartes set up in the 17th century. The fundamental question was one of epistemology: what’s the relationship between our minds (i.e., the operations of consciousness) and reality?

Pragmatism has an affinity with various idealist philosophies that argue against a representationalist theory of mind, which basically holds that our mind mirrors “the way things really are.” That is, there exists a material reality independent of us; we come along and perceive it through our senses; and thus material reality gets reproduced accurately in our minds. But simply mirroring reality, say the Pragmatists, is not the purpose of having minds. James puts it as follows:

The knower is not simply a mirror…passively reflecting an order that he comes upon and finds simply existing. The knower is an actor, and co-efficient of the truth…Mental interests, hypotheses, postulates, so far as they are bases for human action—action which to a great extent transforms the world—help to make the truth which they declare. In other words, there belongs to mind, from its birth upward, a spontaneity, a vote. It is in the game.

Students of philosophy will hear in these words a more reductive version of Kantian idealism, the notion that the mind constitutes reality through its categories of perception. Kant was able, through a staggering amount of work, to build truth and ethics back into philosophy. Pragmatism, though, leans into his solipsistic implications by removing his notion of a “neumonal” realm, i.e., pre-representational objects that are “out there,” independent of our minds. We cannot know things intuitively at all, they insist—not even through the sublime. That is, there’s nothing outside the operations of our consciousness. Ideas don’t refer to “things themselves;” they refer merely to other mental representations. When we hear the word tree, we do not perceive an actual tree; we perceive our mental conception of a tree. The pictures in our minds are all there is, literally. James put it thus:

All our thoughts are instrumental, and mental modes of adaptation to reality, rather than revelations of gnostic answers to some divinely instituted world-enigma.

Dewey writes in a similar vein:

Things are what they are experienced as…knowledge is not a copy of something that exists independently of its being known, it is an instrument or organ of successful action.

If ideas are all there is, how do we discern correct ones from false? Here Peirce introduced what he called the Pragmatic Maxim, a rule for clarifying the meaning of hypotheses by tracing their “practical consequences”—their implications for experience in specific situations. We clarify a hypothesis by identifying the practical consequences we should expect if it’s true. Peirce puts it as follows:

Consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of those effects is the whole of our conception of the object.

As Edmundson explains, Pragmatism is anti-foundational. It seeks a ground for philosophy without presuppositions. Peirce argued that the meaning of any statement lay in its predictive value. The Pragmatic Maxim is often encapsulated by a pithy saying: it’s the fruits, not the roots. That is, the “correctness” of an idea—epistemological, ontological, ethical, etc.—lies in the consequences it bears in our experience, not some intrinsic quality like nature or form. To describe an element as highly flammable, for instance, is not to perceive in it some metaphysical quality (as Aristotle asserts). It’s rather to say what will happen if you take a torch to it. James expands on this notion:

Ideas become true just in so far as they help us to get into satisfactory relation with other parts of our experience…The true is the name of whatever proves itself to be good in the way of belief, and good, too, for definite assignable reasons…Any idea upon which we can ride; any idea that will carry us prosperously from any one part of our experience to any other part, linking things satisfactorily, working securely, saving labor; is true for just so much, true in so far forth, true instrumentally.

In response to these claims, a number of objections arise that classical Pragmatists never quite answered: Just what sort of “effects” and “practical consequences” should we consider? The consequences for ourselves as individuals? For society? Pyschological consequences? Behavioral? Political? Regardless, Pragmatism takes such interests for granted; it doesn’t account for how our judgments about the value of ideas are themselves valid. We form beliefs to get what we want, but where do we get our wants? You quickly run into an infinite regress.

A second, related problem: Some beliefs make people behave in decidedly impractical ways, if by practical we mean relating to everyday tasks, business affairs, and material success. How do we account for this? Pragmatists might respond that such ideas are mental mistakes and cognitional errors that we will, over time, work out and eliminate as a collective. But social progress has often come about from brave people giving their all—even their lives—for ideas that were impractical at the time, if not outright insane. The abolitionist movement jumps out immediately. As Schopenhauer put it, “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

A third objection: If there’s no truth independent of our minds, then isn’t everything relative and nothing right or wrong? In his essay, Edmundson hangs his hat on this problem, arguing that Pragmatism degrades ideas into their “cash value,” that is, their utilitarian or instrumental worth. Universal norms, ethics, even shared facts seem impossible. “When I hear talk about my narrative and yours,” he says, “when I hear talk about my truth and yours…when I hear that politics is about conflicting stories, with the assumption that there are no determinate facts that make one story better than the rest, I think of [Pragmatism].” Pushed to its extreme, he says, it seems to lead to a Machiavellian ethic of the ends justify the means. Enter Trump:

Trump knew—and knows—that Truth has gone on vacation; his acolytes know it, too. They are not nihilists…for they are prepared to latch onto pragmatic truths that will get them what they want…Like a committed pragmatist, [Trump] uses words to influence his listeners and accomplish his goals…What distinguishes Trump is that he has never claimed—at least not for very long—to have any enduring values in mind…Is Trump a racist? Is Trump a sexist? Is Trump a patriot? Is Trump an advocate of freedom? Trump is not anything. He is what will get him what he wants at any given moment.

Edmundson also locates this pernicious expediency in Trump’s supporters:

Many voters…supported his candidacy in explicitly pragmatic terms. Trump invited them to do so not through his half-hearted claims to share their values, but through his repeated insistence that he was a winner who would deliver what they wanted. It was this more than anything that made him our first true pragmatist president.

II.

Pragmatism’s not my preferred philosophical system, for some of the reasons just stated. I gravitate toward Phenomenology, which emerged at the same time in Europe through the writings of Edmund Husserl. Phenomenology takes a similar starting point as Pragmatism but offers a more rigorous account of how consciousness intends things themselves, not just internal mental images. It successfully demonstrates how mind and reality are in relationship through conscious attention. Thus it gets you to a conception of shared public truth more smoothly than Peirce and James.

Yet I do want to defend our home-grown philosophers from this charge of Trumpism. Far be it from me to question a distinguished professor, but Edmundson creates something of a straw man in his depiction of Pragmatism. To begin with, Peirce himself didn’t think Pragmatism led to relativism, individualism, or arbitrariness. Rather, he defines truth as the product of converging opinions through the process of inquiry (as opposed to some a priori cause of ideas):

The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real. That is the way I would explain reality.

“Truth is the end of inquiry,” he says, where end is to be understood not as finished (some point in time when all human questions will be settled) but as a goal or telos. Peirce believed that habits of thought and action, far from being mere instrumental adaptations to the environment, are steps on the universal road from indeterminacy to law. Organisms have the potential to produce a variety of responses to a given stimulus. But those responses cannot be random, since if they are, law would not be possible. Rather, they cluster around a norm. The universe, he held, is evolving from a condition of chaos toward a condition of absolute law, in which chance will disappear and all habits will be fixed.

This includes our beliefs. As the universe becomes more predictable, our beliefs about it become truer, less individualistic, more fixed:

Just as conduct controlled by ethical reason tends toward fixing certain habits of conduct, the nature of which…does not depend upon any accidental circumstances, and in that sense, may be said to be destined, so, thought, controlled by rational experimental logic, tends to the fixation of certain opinions, equally destined, the nature of which will be the same in the end, however the perversity of thought of whole generations may cause the postponement of the ultimate fixation.

In Peirce’s account, we are evolving to complete epistemological rapport with reality. He called this final condition, “concrete reasonableness.”

James parted ways with Peirce on this point and rejected his idea of ultimate determinism. But he and Dewey shared his conception of a universe still in progress, a place where no conclusion is foregone and every problem is amenable to the exercise of “intelligent action” (in this way, Pragmatism dovetails with Process philosophy). The key to intelligence, for them, is that it’s collective, public, based on experimentation. They believed in science and communal inquiry, not radical relativism or narcissistic atomization. Pragmatism was an optimistic system, grounding the progressive movement in politics at the time. As Louis Menand says in his 2001 book The Metaphysical Club, James was temperamentally averse to the industrial capitalism and imperialism that defined America in his day, which exposed the country’s “mindless drive toward expansion, conglomeration, massification.”

Instead, when it came to politics, economics, society, he staked out an anti-corporate, anti-nationalist position:

I am against bigness and greatness in all their forms, and with the invisible molecular moral forces that work from individual to individual, stealing in through the crannies of the world like so many soft rootlets…The bigger the unit you deal with, the hollower, the more brutal, the more mendacious is the life displayed. So I am against all big organizations as such, national ones first and foremost, against all big successes and big results; and in favor of the eternal forces of truth which always work in individual and immediately unsuccessful way underdogs always, till history comes, after they are long dead, and puts them on top.

Dewey didn’t like industrial capitalism either, though he eschewed the confrontational approach advocated by socialists like Eugene Debs. He took a reformist strategy and became a champion of social amelioration, heavily influenced by his friend Jane Addams. He was one of the world’s foremost education theorists, and (with James) believed that through the hard and humane sciences, we could perfect society. The key to this improvement was democracy, which he interpreted as the practice of “associated living”—cooperation with others on the basis of tolerance and equality. Menand captures this Pragmatist commitment to common life:

The political system their philosophy was designed to support was democracy. And democracy, as they understood it, isn’t just about letting the right people have their say; it’s also about letting the wrong people have their say. It is about giving space to minority and dissenting views so that, at the end of the day, the interests of the majority may prevail. Democracy means that everyone is equally in the game, but it also means that no one can opt out…Democratic participation isn’t the means to an end, in this way of thinking; it is the end. The purpose of the experiment is to keep the experiment going.

Contra Edmundson, then, nothing could be further from Pragmatism than Trump. Trump is a bullshit artist, a confidence man right out of the Gilded Age. James hated such figures, as did Dewey. As a person, Trump is a troglodyte who rejects intellectual inquiry, denies science (he disputed a weather projection, for God’s sake), and peddles base conspiracy theories. He cares not for collective well-being, which is the heart of utilitarianism, but personal enrichment and pleasure. He made his wealth through big business deals that crushed little people and ended up to be massive follies. And he hates democracy: he does not wish to keep the experiment going, but rather to end the game once and for all, with himself as the sole winner. Everyone else, in his words, is fired.

The real root of Trumpism, as I’ve argued, is fascism, motivated not by any philosophy but rather “subterranean emotions and passions,” as Robert Paxton says. In fact, some call it “technologically equipped primitivism,” which aptly sums up Trump on Twitter. Fascism’s intellectual influences (if it has any) come not from Emerson or Dewey, but from a bastardized reading of Nietzsche, along with obscure 19th-century thinkers like George Sorel and Gustave Le Bon. In the U.S., it also takes its inspiration from the Lost Cause writings of Jefferson Davis and other defeated Confederate leaders. The Pragmatists did traffic in some of the social Darwinism and fears of demographic contagion that motivate fascist anxieties. But this is a mere, if unfortunate, coincidence.

The American variant of fascism—Christian nationalism—likewise couldn’t be more opposed to Pragmatism (over at The Cottage,

has an informative ongoing discussion of the ideology.) The latter, as we’ve seen, rejects ideologies that make absolute claims on truth. In contrast, white evangelical Christians seek to impose their brand of retributive justice, moral absolutism, and authoritarian conceptions of God onto everyone. They peddle this totalizing worldview through a corrupt, literalist, purposefully stupid interpretation of the Bible, a book many of them have never actually read. Nevertheless, they appeal to it as a cultural weapon of ultimate appeal, just as they bow to Trump as their cult leader. What strikes me about these people is their uncompromising certainty of what is true—not their lack of it. This closed, theocratic mindset would’ve horrified Peirce, James, and Dewey.Pace Edmundson, it’s not that America’s political turmoil is being caused by a lack of ideals. Quite the contrary. Yes, many politicians are empty suits who would sell their grandma for a vote (cough, Kevin McCarthy). But everyday people aren’t like that. Not that this is necessarily better—some hold ideals that are outright toxic, a nostalgic fantasy of white Christian America that never was. Armed with this perverse principle, they assaulted the Capitol on January 6 out of fear of the Great Replacement.

Other Trump supporters aren’t motivated by racial paranoia, but plain old disillusionment, the shadow side of idealism. Many folks in rural Yankeedom and the Midlands have been made cynical by the yawning gap between the lofty claims of the Declaration of Independence and the failures of governing elites to realize them. The ravages of neoliberalism to life, liberty, and happiness have made these voters desperate for someone—anyone—to break the oligarchy. In their pain, they’ve turned to populist outsiders: Sanders and Trump. Americans have ideals. It’s the hallow, rapacious capitalist overlords who dominate this country who don’t. And none did better under Trump than they.

Edmundson begrudgingly admits that beneath the sometimes pedantic rhetoric of today’s Left, you can hear genuine ideals struggling to express themselves. He names three of his own that he believes universal: courage, compassion, and wisdom. We can debate the merits of this claim, but no one would endorse those values more than men like James, Peirce, and Dewey. When you read their lives, you’re bowled over by their intellectual bravery, compassionate reform, and commitment to truth. James’s devoted his efforts to combatting atheism, after all, and making room in the modern world for God (his Varieties of Religious Experience being the greatest account of mysticism ever penned). Dewey’s one of the most seminal philosophers of democracy ever produced. If nihilism afflicts some Americans today, it’s not the fault of Pragmatists. In fact, recovering their intellectual legacy might just restore hope in us all.1

Sources:

Menand, Louis. The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002.